September 13, 2020I am not proposing new style, which is new rules, but freedom,” Yves Saint Laurent declared provocatively in 1969. A man of his word, the French fashion designer pioneered “cross-design” in fashion, taking inspiration from street trends to modernize haute couture.

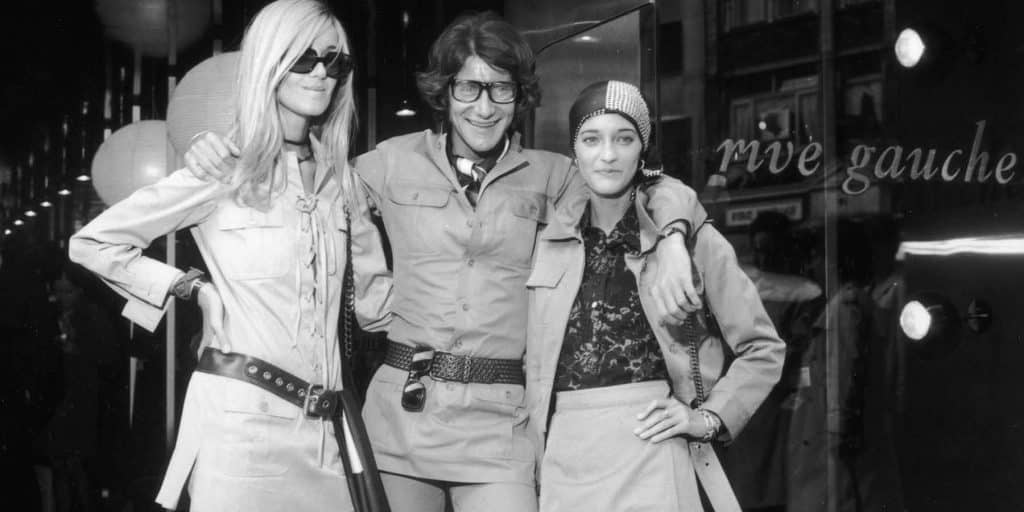

He was the first to launch a ready-to-wear label, YSL Rive Gauche Prêt-à-Porter. He was the first couturier to open boutiques for both men and women. Using traditional menswear fabrics and designs for women, Saint Laurent also literally cross-dressed, giving men and women alike chic pant suits, elegant tuxedo jackets and urban safari gear.

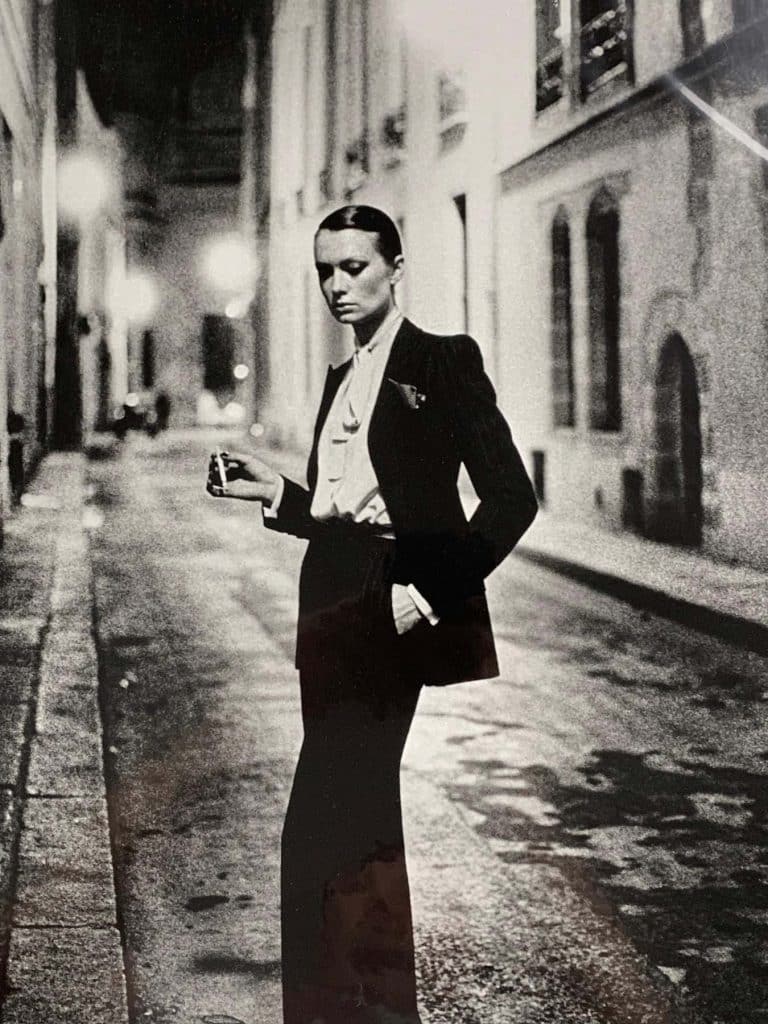

By blurring gender-specific design, he empowered individual style while creating a scissor-sharp fashion aesthetic of sensual ease and beauty. Many of his designs are today considered timeless classics.

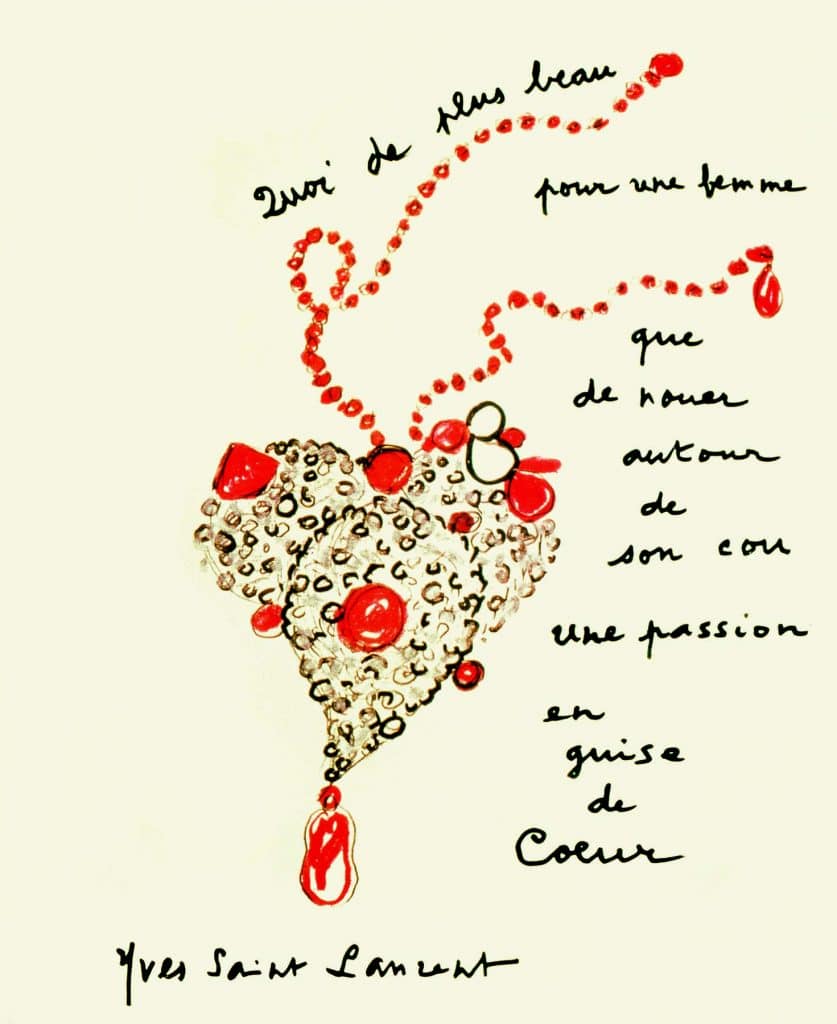

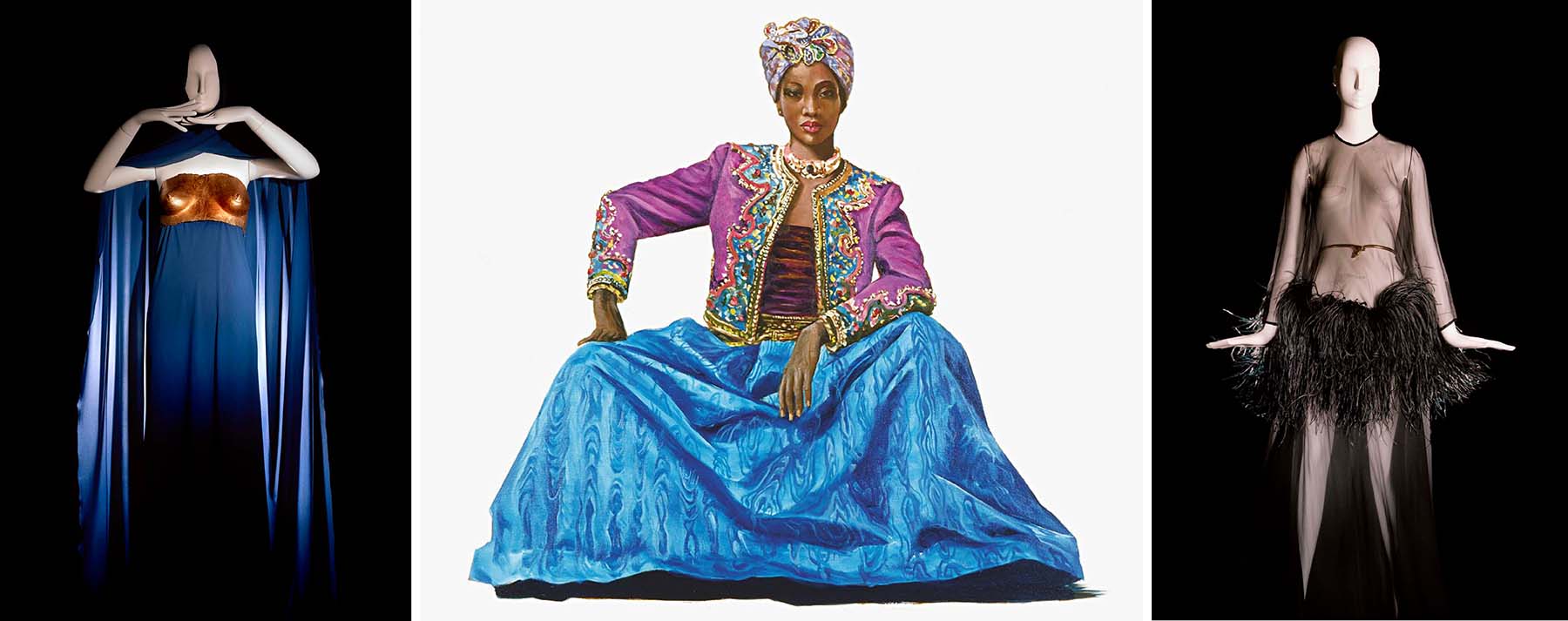

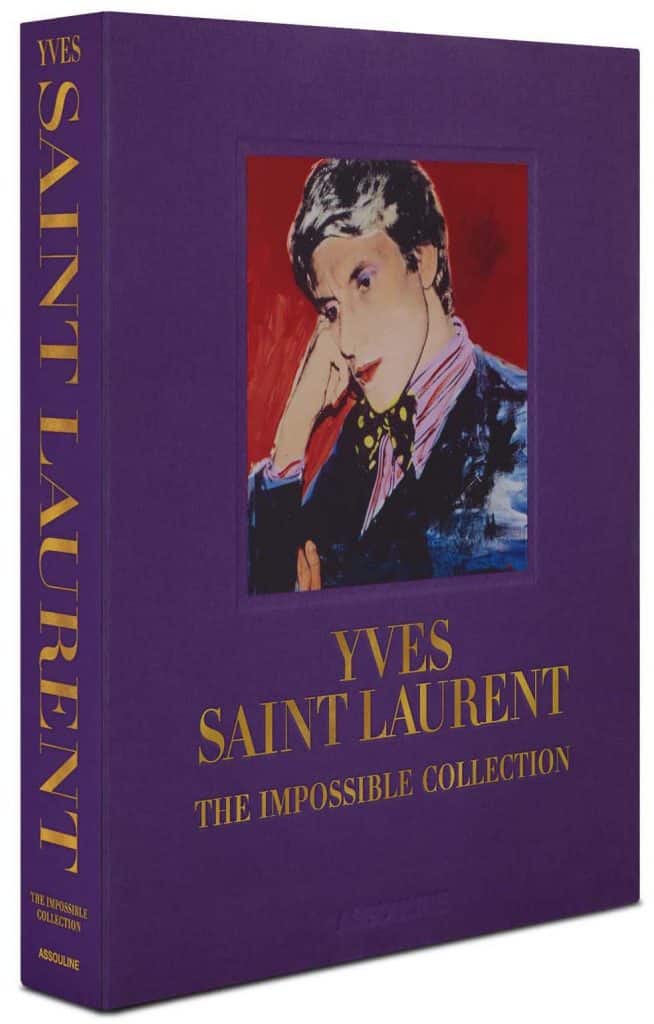

Yves Saint Laurent: The Impossible Collection is the latest addition to Assouline’s weighty handcrafted Ultimate Collection, a luxury limited-edition series that covers art and culture through the ages. This volume takes the reader on a lush visual journey through Saint Laurent’s career, via 100 photographs capturing most of his historically influential designs.

Presented in chronological order, they are interspersed with his renowned fashion illustrations, as well as period photographs of people and places, interiors and exteriors by such famed lensmen as Richard Avedon, Guy Bourdin and David Bailey.

A press snap of Bianca Jagger at her wedding to Mick shows her sporting the legendary white tuxedo jacket Saint Laurent made for her. At this point, which fashion notable hasn’t worn Le Smoking, as it came to be known?

There are photos of Saint Laurent’s stylish loyal muses, including actress Catherine Deneuve, Loulou de la Falaise, Betty Catroux and Hélène Rochas. Marisa Berenson is pictured in his Paris apartment, one of many tantalizing shots of interiors — among them, the designer’s couture atelier, decorated by Jacques Grange; the exotic library at the Villa Oasis, decorated by Bill Willis; and Saint Laurent’s last home, in Marrakesh.

Also in the mix is a Horst P. Horst photograph of the man himself, reclining on a colorful mosaic of kilims and carpets in the villa’s garden, from a 1980 issue of Vogue.

As Saint Laurent expert and fashion journalist Laurence Benaïm points out in her rhapsodic introductory essay, it is impossible to include all of the designer’s masterpieces. With a witty subversive nod to Disney’s Evil Queen and her obsessive questioning of her own superlative “fairness,” Benaïm, the author of the reference biography Yves Saint Laurent (Grasset), among other titles, states that each design calls out, “Mirror, mirror on the wall, I am the most beautiful of all.”

Andy Warhol‘s 1974 polychromatic portrait of a pensive 38-year-old Saint Laurent is on the front of the book’s protective purple-silk clamshell box, an appropriate tease for what’s inside. The masterful deployment of color was among Saint Laurent’s many renowned techniques, which also include sensuous draping and stunning juxtapositions of fabric.

Born to French parents in Oran, Algeria, in 1936, Saint Laurent went to Paris at age 17 to study fashion at the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture. Just two years later, in 1955, his remarkable sketches were shown to Christian Dior, then the world’s reigning couturier, who hired him immediately.

Surprisingly soon thereafter, Dior publicly chose him as his successor, which sadly proved prescient when the fashion legend died unexpectedly, in 1957. A mere slip of a youth, the 21-year-old Saint Laurent was nevertheless up to the challenge.

He shook the traditional couture clientele to its core with youthful silhouettes and styles like the A-line trapeze dress that hung with seeming effortlessness from the shoulders, the antithesis of the pinched waists and molded skirts that had been all the rage after the deprivations of World War II.

Other highly coveted collectibles poured from his imagination, such as the black crocodile motorcycle jacket, an early intimation of Saint Laurent’s passion for subverting — or is it obverting? — street style, which was then dominated by the anti-bourgeois beatniks of Paris’s Rive Gauche.

After a mandated spell in the torturous French military, Saint Laurent suffered a nervous breakdown and was dismissed by Dior in 1962. Out of the ashes rose the Age of Yves. With Pierre Bergé, his then-lover who became his lifelong business partner and friend, the designer founded Yves Saint Laurent YSL to encompass prêt-à-porter, or ready-to-wear.

In 1966, they opened the first YSL Rive Gauche women’s boutique in Paris, followed soon thereafter by YSL Rive Gauche for men. Saint Laurent had given birth to a global brand.

Benaïm has curated a vital mix of exemplary styles from Saint Laurent’s prolific 40-year reign, many of which he reworked throughout his career. One of these is the famous peacoat from his first haute couture collection, a design that has been completely assimilated today but shocked then — a rough-and-ready workman’s jacket for ladies of leisure?!

Saint Laurent’s revolutionary Mondrian mini dress from 1965 is a core element of his fashion biography. It is a prime example of how Saint Laurent, an avid art lover and collector, looked to painters, from Goya to Picasso, Ingres to Matisse, for inspiration.

With its pure lines and hues, Mondrian’s ground-breaking 1935 color-block painting Composition C transmutes beautifully into a dress that is highly valued by collectors of contemporary fashion and widely copied commercially to this day.

The design is the epitome of Saint Laurent’s aesthetic, requiring a meticulous hand piecing of each color block so that, despite the body’s curves, the visual plain is as flat as a canvas when the garment is worn. Mondrian’s purity met its match in Saint Laurent. (Benaïm informs us that one of the pattern cutters was another renowned perfectionist: a young Azzadine Alaia!)

The Mondrian dress is shown worn on the cover of Paris Vogue, as well as on British Sudanese model Alek Wek in a photographic trifold by Christoph Sillem from 1998. Saint Laurent consistently used Black models, like Mounia, Iman and Naomi Campbell, and he drew endless inspiration from different ethnicities and cultures, in no small part because of his Algerian roots.

Long before Madonna made the pointed breastplates of Gaultier’s corset famous, in 1990, Saint Laurent designed the 1967 African Bambara collection of midriff-baring minidresses, one of which — shown in the book — has totemic breast cones. The series not only represents a staggeringly beautiful interpretation of the continent’s art but also showcases the embroidery of such haute-couture ateliers as maisons Lesage and Lanel — astonishing compilations of threaded beads, feathers, raffia, gold yarn, straw and wood.

The book also includes sculptor Claude Lalanne’s brilliant galvanized-copper breastplate and torso plate, which she molded on a naked Veruschka for Saint Laurent’s 1969 chiffon sheaths. They embody the designer’s belief that “[n]othing is more beautiful than a naked body.”

He was famously the first designer to strip to sell, appearing in Jeanloup Sieff’s 1971 advertising shot for YSL men’s perfume wearing nothing but long hair and specs (women bought the perfume, too!). This picture is not shown. Appearing in its stead is the more subtly provocative photo of model Jean Shrimpton by David Bailey from the same year. Hair pulled back, she unsmilingly dares the viewer in a see-through sleeveless polka-dot blouse with a menswear pinstripe pant suit, a clear marker of Saint Laurent’s innate belief in the freedom of genderless dressing.

The “ambiguity,” he said, intrigued him. “Besides, it’s how we live now,” he told fashion sociologist Frédéric Monneyron for his 2008 book La frivolité essentielle, one of many great quotes with which Benaïm studs the book. You can visualize the designer shrugging the subject off.

Handsome, sexy and willful, Saint Laurent was also psychologically fragile, and he made no secret that, throughout his life, he struggled with inner demons and with a dependence on “those fair-weather friends we call tranquilizers and drugs,” which he attributed to his youthful spell in a military hospital.

At his best, like any artist, he used his nervous energy to feed his fertile imagination with all that inspired him. Creation gave him momentary peace, his confidence unassailable. “Nowhere is Saint Laurent more excessive than in his talent,” Cathy Horyn penetratingly noted in the New York Times in 2000.

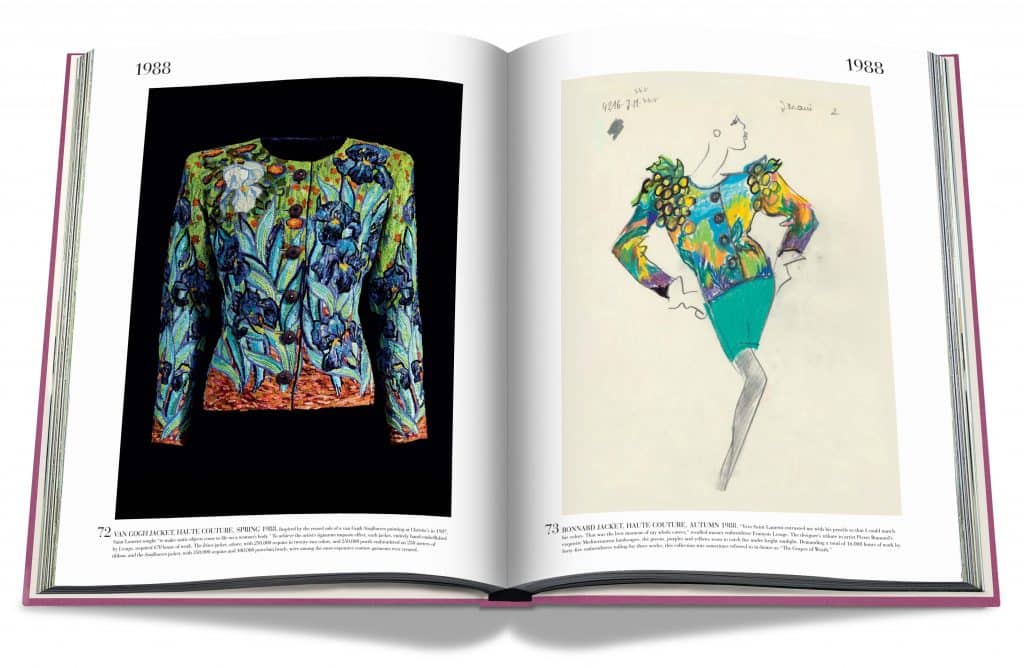

And no historical haute couture collection is more excessive than Saint Laurent’s Spring/Summer 1988 line, represented in the Impossible Collection by an image of his Van Gogh–inspired “Irises” jacket. Entirely hand embroidered by Lesage on 273 yards of ribbon, it took 670 hours, 250,000 sequins in 22 colors and 250,000 pearls to make. Among the most expensive couture garments ever, the “Sunflowers” version sold for $450,000 last year at Christie’s in Paris.

“I am no longer concerned with sensation and innovation, but with the perfection of my style,” Saint Laurent said four years before retiring, in 2002. After a long period of ill health, he died at his home in Paris on June 1, 2008. He was 71.

By the end of Yves Saint Laurent, The Impossible Collection, one is left breathless. Benaïm has answered the Disney queen’s question with panache. This collection embraces Saint Laurent’s most beautiful designs. It would indeed seem impossible that one man could consistently create such radical beauty, but seeing is believing! By breaking down haute couture’s traditional exclusivity, he instinctively and uncompromisingly democratized that beauty. With hindsight, his youthful proposal to free fashion from style rules can be seen as a promise, one that he kept.

Saint Laurent gave each and every individual the right to express and own their uniqueness. As he said back in 2008, it is how we live now.