August 3, 2015William Wegman holding a cutout likeness of Bobbin, one of several Weimaraners he has owned and photographed over the past 45 years. Photo by Tim Mantoani. Top: Eames Low, 2015 (detail). All photos courtesy of Senior & Shopmaker Gallery, unless otherwise noted.

Enter William Wegman’s sprawling live/work space in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, and be prepared for two large, barking canines to come bounding across the floor to greet you. They are Flo and Topper, and anyone even casually familiar with Wegman’s prolific career will recognize them as two of the troupe of pale-eyed Weimaraners with silky smooth, taupe-colored coats that the 71-year-old artist has photographed and filmed for 45 years. On a warm morning in late spring, the dogs cease barking at Wegman’s gentle command, then stick close to their master’s side as he ambles past the ping-pong table, through the comfortable family living room, out to the roof garden and up a staircase to a higher rooftop where he and his 20-year-old son, Atlas, practice their hockey moves, sans ice. Flo and Topper lope along with Wegman until we move downstairs and he bars them from his studio, leaving them to whine mournfully on the other side of the closed door. “They’re more demanding than any dogs I’ve ever had,” he says, telling Topper to quiet down, “and I’ve had Weimaraners since 1970.”

Plenty of artists are closely associated with their muses: Pablo Picasso and his many lovers; Alex Katz and his dark-haired beauty of a wife, Ada; even Chuck Close and the heavy-lidded composer Philip Glass. But few are as inextricably linked as Wegman and his Weimaraners. Since 1970, when Wegman acquired his first Weimaraner puppy, named Man Ray in homage to the seminal Surrealist photographer, to today, when he regularly uses half-siblings Flo, four years old, and Topper, three, in his large-scale color photographs, Wegman has created his own instantly recognizable brand of contemporary art.

An Eames walnut stool provides a precarious perch for Flo in Figured Base, 2015.

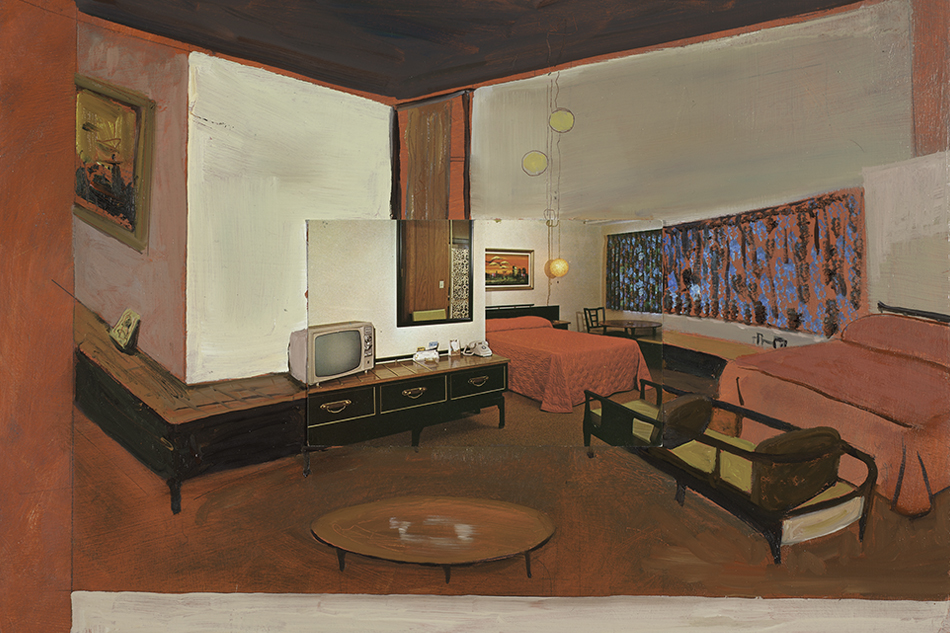

For his latest twist on the theme, this year Wegman replaced his signature pedestals with iconic mid-century-modern furniture produced by Herman Miller. There’s Flo in profile on a bright red Eames chair, in Eames Low, and seen demurely from behind on a yellow one, in Ocean View. In One, Two, Three, etc., a set of nine images, the two dogs move along a row of green, red and yellow Eames chairs. In On and On, a four-panel work, double images of Flo face off from opposite ends of George Nelson’s long wood platform bench.

The idea for the series came from Wegman’s wife, Christine Burgin, a well-regarded former gallerist who now publishes exceptionally beautiful books. “It was just, ‘Why don’t you use some more colorful, more interesting props, Bill?’” he recalls her saying. To which Wegman replied in his easy-going manner, “‘Okay.’ I like taking suggestions from the audience. It forces me to think differently, to be outside my comfort zone.”

Wegman jokes that Burgin may have had ulterior motives. “Christine wanted to spruce things up,” he says with a chuckle. “I think secretly she wanted a trade — we have crappy furniture.”

Wegman selected the pieces from Herman Miller’s midtown New York showroom, and then began experimenting in the studio as usual. Particular set-ups have always worked better with particular dogs. Candy (2001–15) liked being airborne, for instance, while Batty (1989–2003) was adept at gracefully draping herself over any object. So Wegman was not surprised that he preferred using one dog more than the other for the new series. “Once I started to work with it, I realized that certain tones and curves worked especially well with Flo,” he says. “She’s a little heavier than Topper. Topper looked amazing on studio props, like pedestals.”

What Wegman hadn’t expected was for the chairs, stools and benches to transcend mere prop-hood, making him feel as if he were collaborating with the late furniture designers themselves. “Somehow, the furniture itself became almost a character,” he says. “That was different. The other props I’ve used were almost lacking in character.”

A still from the video Spelling Lesson, 1973–74, in which the artist attempts to teach a distinctly human skill to his first Weimaraner, Man Ray (detail)

Images from the Herman Miller series, titled “Good Dogs on Nice Furniture,” will be included in the San Jose Museum’s upcoming Wegman retrospective, “Artists Including Me,” opening October 3; Herman Miller is also planning an exhibition of the work. Select images are available on 1stdibs through Wegman’s New York dealer, Senior & Shopmaker Gallery, in Chelsea.

Wegman had what he remembers as a “wonderful childhood” in western Massachusetts. His father was shot down in a B-17 bomber in 1943 and spent the rest of World War II as a prisoner of war; Wegman was two years old when he met him. His mother was the “bad cop,” he says, and his dad, a “sweetheart.” Wegman went to the Massachusetts College of Art, in Boston, where he was so shy, “I would eat my lunch in the bushes.” He then enrolled in grad school in painting at the University of Illinois, and later took teaching jobs in Wisconsin and Los Angeles. His quirky conceptual art included videos like Stomach Song (1970–71), in which his bare torso resembles a face — with nipples as eyes, navel as mouth — “singing” a nonsensical ditty, and black-and-white photographs such as One or Two Spoons/Two or Three Forks (1972), in which one spoon, two forks and only the handle of a fourth utensil are visible, leaving the exact composition an insolvable mystery.

The first month that Wegman was in L.A., he adopted Man Ray, who was about six weeks old. He began working with the pup almost immediately because, Wegman claims, “he sort of demanded it. He hypnotized me in a way.” The one year Wegman did not photograph or film Man Ray, when the dog was eight, “he was pretty miserable.” The set-piece portraits of the sullen-looking but photogenic Man Ray offered a radically new take on conceptualism and Pop art alike.

“Somehow, the furniture itself became a character.”

The new series wasn’t the first time Wegman posed his dogs on furniture. Battina sits on a plush vintage chair in Untitled, 1997.

In 1972, Wegman moved to New York, where he began showing with Sonnabend Gallery right away and his reputation continued to grow in the art world — and where he also found crossover success making videos for Saturday Night Live. He started hanging out with the hard-partying SNL crowd, including John Belushi. Wegman drank to overcome his shyness and used cocaine to fuel his time in the studio. “Then, when I stopped in 1981, I got incredibly organized, very neat, and that was not so good,” he says. “I have a low opinion of the work from the mid-eighties. I’ve done some really awful things, and didn’t know it at the time. It takes some space and time to assess what you’re doing.”

Man Ray’s death, in 1982, came as a shock and hit Wegman hard. “I was supposed to pick him up the next day [from the animal medical center], and I got a call at seven in the morning saying, ‘Oh, he died.’ I just didn’t handle that well at all. I was a mess.” He still has nightmares that Man Ray is alive: “‘Man Ray, where did you go? I’ve been looking for you.’ Then I realize it’s a dream, a terrible dream.”

He waited several years before adopting his next Weimaraner, Fay Ray (a nod to King Kong starlet Fay Wray), and another year before photographing her. Fay Ray seemed to help him find his mojo again, as he grew to accept his special knack for photographing his dogs. “With Fay, I didn’t want to keep doing the dog photography thing, but I realized I couldn’t keep a pet as a pet. She needed a job,” he says wryly.

Fay later had puppies, producing a veritable acting troupe that led to Wegman’s expansion into popular children’s books and whimsical Sesame Street videos. “It really exploded the whole thing, and I got used to multiple dogs,” he says. “Now, I don’t want to be without more than one dog. Four is too many; two is really good.” (Though Wegman raised several descendants of Fay, who died in 1990, Flo and Topper now represent a new line.)

Fay Ray (left) and Battina wear floral dresses in Dolls, 1991. “A big breakthrough,” Wegman says, “was when I first started to anthropomorphize them, turn them into people.”

Some of his most well-regarded photographs were made with a Polaroid 20×24 camera, but he has since moved with the times to digital formats. “A big breakthrough, which was a rule that I broke, was when I first started to anthropomorphize them, turn them into people,” he says. “I swore I would never do that. I didn’t with Man Ray. He was an elephant or a frog, but he was never a person. But when I added the hands and the arms, they became more like characters from mythology. They seemed more interesting than just a dressed-up dog. That was born from the verticalness of the Polaroid camera.”

Wegman trains the dogs himself, though, he says, “if you talk to Christine, you’ll realize they’re not well trained at all. They’re great in the studio. When the lights go on, they get almost competitive to be chosen. If I’m working with one, I have to put the other just outside the frame and give him or her something to do.” Only Candy seemed to dislike being shot. “She wanted to be chosen, but as soon as you pointed the camera at her, she’d make a really ugly face and turn her head. It was almost comic to see what kind of awful picture she would make.”

Wegman does not reward his models with treats: “I don’t want the drool factor.” He has, however, used food as a tool, smearing cheese on a page so that a dog would keep “reading” it in a video, and leaving a trail of crumbled Oreos for a dog to follow. Wegman does not script his films, and one of the hardest things he had to engineer was getting three dogs to look in different directions simultaneously while shooting a video on his property in Maine, where he has long spent summers. “If I call one—‘Fay!’—they all look at you,” he explains. “We were inside one of my cabins. One thing I did was talking through tubes so I could throw my voice all over the place. The thing that worked great was I threw pebbles on the roof, and they rolled down the different facets of the structure, and the dogs looked in all the directions.”

In A Step Up, 2014, Flo balances on blocks that nod to the Constructivist art movement.

Man Ray and his successors provided Wegman with reasonable surrogates for people: models who were alive and, at least seemingly, both intelligent and emotive — yet at a remove. “Humans are just so literal in a way, and I’m not very comfortable asking another person to do this or that,” Wegman says. “The dogs require it, expect it, of a person.”

The other upside to working with dogs is their infinite patience. They’re content to loll around the studio while Wegman carefully composes shots. “They allow you to think as long as you want to,” he says. “A person would want you to hurry it up.” He occasionally photographed his first wife, Gayle, but “she’d just get so annoyed with me.” With the Weimaraners, he adds, it’s almost as if he were alone in the studio. He doesn’t mind having assistants around either and has sometimes used them in shots with the dogs. (He stopped making self-portraits in his 30s, when seeing himself aging in the photos started to bother him and his transition to color required lights that made him sweaty.)

Perhaps most crucially, the dogs enabled Wegman to continue to inject humor into his art. His well-reviewed 2006 retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum was, in fact, called “Funney/Strange.” There are irresistible images of the dogs in silly costumes or wigs, as well as more subtle turns, like 1998’s Buoys, in which two Weimaraners appear to be sitting on a lake’s surface, or a short film from 1973–74 called Spelling Lesson featuring a deadpan Wegman correcting Man Ray’s misspelling of the word beach. When the dog licks his face, Wegman tells him, “I forgive you, but remember it next time.” A show last winter at Senior & Shopmaker was titled “Cubism and Other -Isms” and cheekily placed the dogs atop cube-shaped pedestals against brightly colored backdrops. In a send-up of Kazimir Malevich’s Constructivism, he balanced the dogs in seemingly perilous poses.

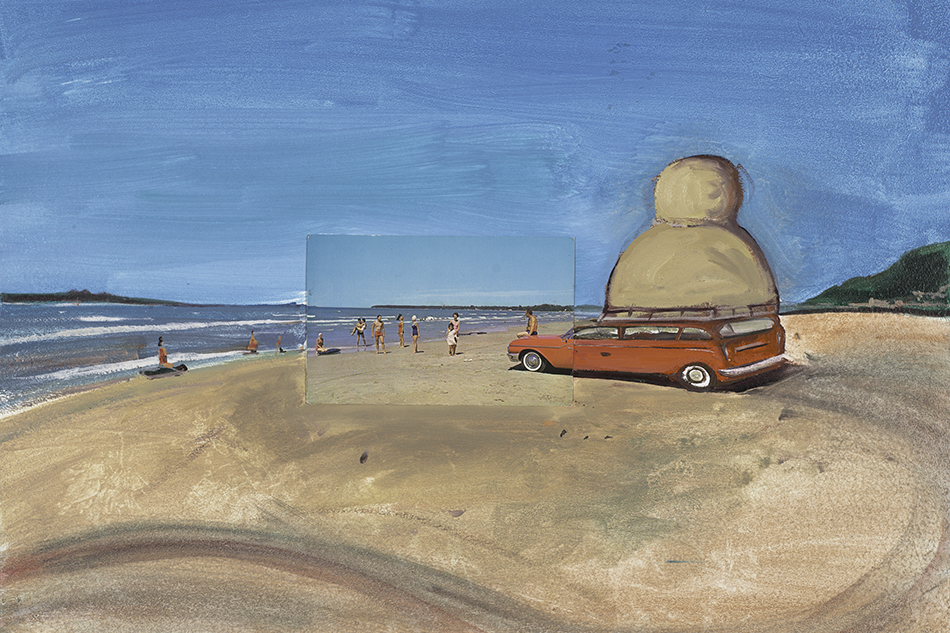

While Wegman is undoubtedly best known for his photography, he has also kept up a painting practice. Early on, he used his own photos as starting points. Then he tried painting around some beaten-up vintage photos by the 19th-century photographer Carleton E. Watkins, which the Jeffrey Frankel Gallery had given him. “That seemed ominous and scary and interesting,” Wegman says. Next he altered greeting cards. “I always like to have something to play with.”

Wegman with Topper and Flo during a visit to Senior & Shopmaker Gallery in New York. Behind them is Lean To, 2014.

In 1992, he made his first “Postcard” painting, connecting several postcards of Maine as if they comprised one complete scene, and then painting additional features around them. For 10 years, he painted on paper, but then switched to wood panels. Having been given whole collections of postcards from friends and family in Los Angeles, Boston and Sweden, he now has a treasure trove of cards from which to choose, from vintage to abstract to text-based. They’re not really organized in any way. “People just dump them on me,” he says. “They’re sprawled all over the place.”

Imagining what might be outside the frame of the postcards, Wegman veers toward the surreal: The eponymous span of George Washington Bridge, 2006, for example, curls into a giant serpent, and the locomotive in (train), 2007, barrels down railroad tracks that turn into the tasteful courtyard of another postcard, where ladies can be seen in elegant dresses. “It’s a lot like when I was a kid — I used to copy pictures out of the encyclopedia,” he recalls.

There’s a natural rhythm, Wegman says, that allows him to alternate between photography and painting. What’s consistent in Wegman’s life now is his family — he gushes about Burgin and their children, Atlas and 17-year-old Lola — and his fanatical devotion to hockey. Wegman, who plays on several teams, is able to keep up with men half a century younger, including his son. “I am sort of an addict,” he says.

The other constant, of course, is his dogs. Every night after 11 p.m., except when the roads are icy, he bikes with them on leashes, three miles to the World Trade Center and three miles back. But Wegman suspects that Flo and Topper may be the last of his Weimaraners. “I could be, like, eighty-five when they’re gone,” he says, “and then I’ll be in an old person’s home, and they don’t take dogs.”