July 26, 2020The world of design is honoring the influential career of Gerardus A. Widdershoven, the founder of the Manhattan gallery Maison Gerard, who died on June 14 of lung cancer.

The Dutch-born gallerist retired from the gallery 10 years ago, after selling it to his longtime partner, Benoist F. Drut, who continues to run it. But he had already made his mark in the business as a pioneer, reintroducing Art Deco and Streamline Moderne to America in the 1970s and, beginning in the early years of this century, adding contemporary collections by top international design talents. He was known for his adventurous taste — he knew what he liked and didn’t like, never wavering, always ahead of the curve — and his scrupulous scholarship. He was a dealer’s dealer and a friend of mine for 40 years.

He is often remembered for his lavishly decorated booths at fairs, particularly the one for the 2000 Art + Design Fair, where he reproduced the octagonal breakfast room that the railroad heir Templeton Crocker commissioned for his San Francisco penthouse in 1928. The stunning black-lacquered room with shimmering Japanese goldfish swimming through it was one of three rooms that the Paris lacquer genius Jean Dunand furnished in the apartment, his biggest job outside France. The panels introduced viewers to Dunand’s exquisite large-scale works. They sold on opening night to the late Manhattan jeweler Fred Leighton.

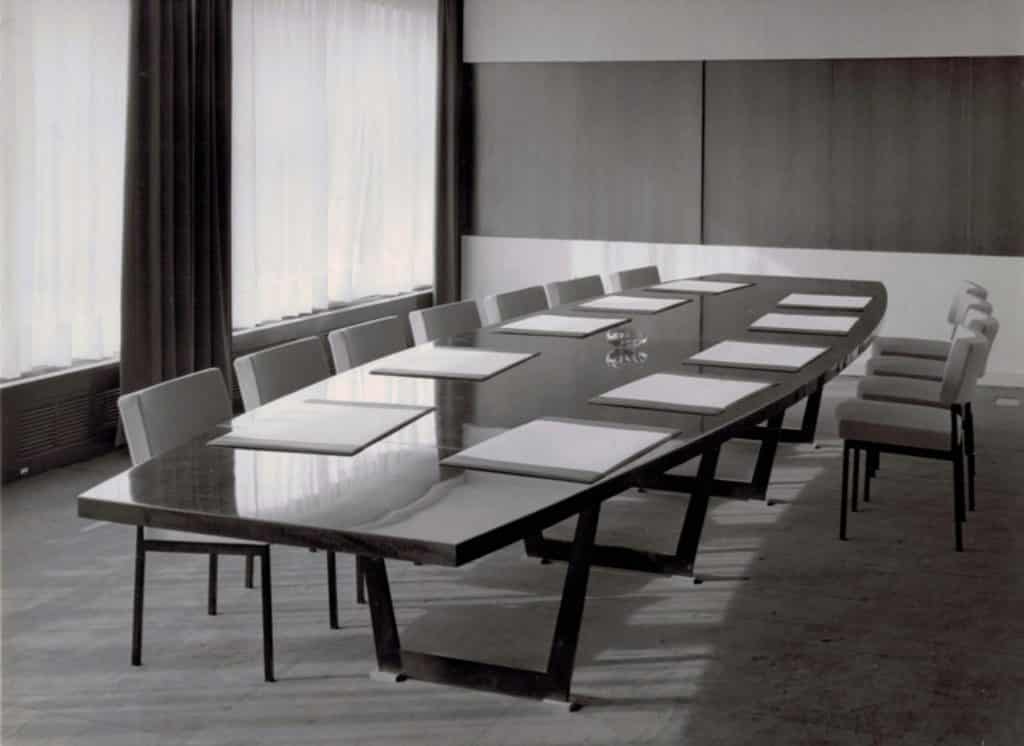

“Gerard was a great connoisseur des arts and, most importantly to me, a good friend,” says the New York architect Thierry Despont. “We worked with Maison Gerard on many projects over four decades, back to when I first opened my practice, and Gerard was consistently discovering unique and extraordinary pieces that our clients instantly loved.”

Unusual for a dealer, Widdershoven was self-taught. He never worked for an auction house or gallery, just followed his fine taste and infinite curiosity. He had to learn by experience because there were no books on French Art Deco in the 1970s.

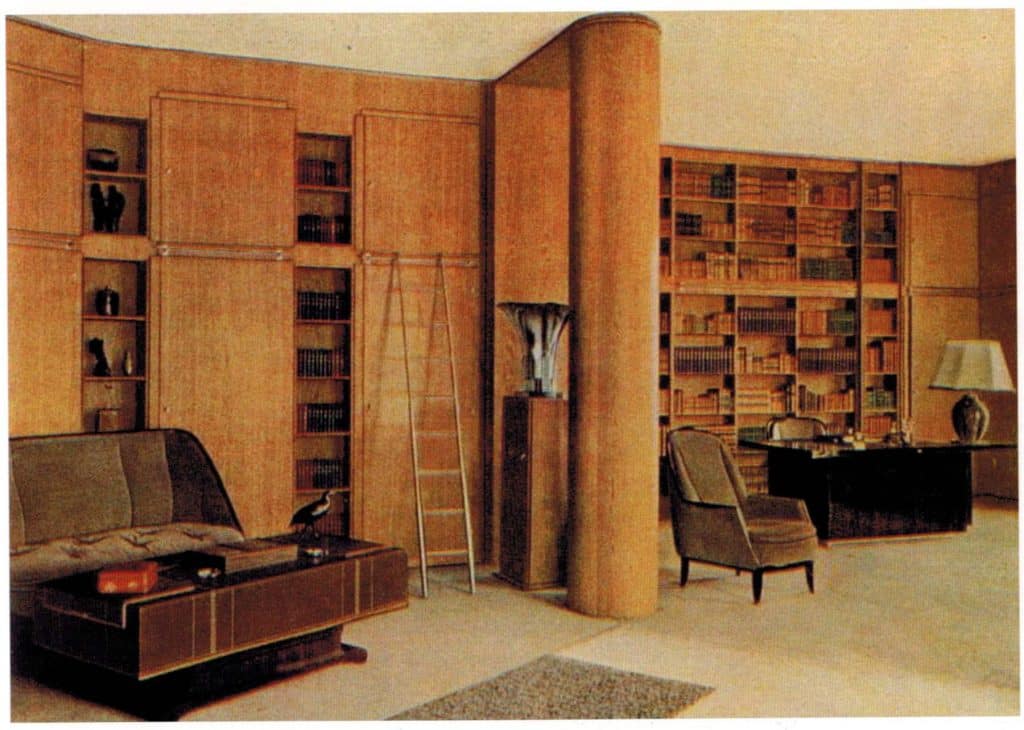

“Along with Karl Kemp’s and Bernd Goeckler’s, Gerard’s death marks the end of the Greenwich Village ‘trinity,’ the three dealers on East Tenth Street whose knowledge and connoisseurship of the twentieth century was inspirational to me and so many other designers,” says Ellie Cullman, cofounder of the Manhattan firm Cullman & Kravis Associates. “A revolutionary in taste way back when, Gerard educated us all in the seminal works of Jean-Michel Frank, Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, Jules Leleu and others, creating a new paradigm with his partner, Benoist Drut, that in the last twenty years encompassed contemporary design masters such as Achille Salvagni and Hervé Van der Straeten. His influence will be felt, without doubt, for years to come.”

Indeed, along with the marquee names that were his stock-in-trade, Widdershoven introduced talents completely unknown to Americans, such as Just Andersen, the early-20th-century Danish sculptor and silversmith, and Salvagni, a contemporary Italian architect known for his lavish materials and fine craftsmanship. “He was an extraordinary person, so generous in sharing his knowledge with us as young designers,” says New York architect William T. Georgis, who designed a couch for the gallery. “He shaped a generation. His legacy will live on in all the designers he informed and sold to.”

“Today everything is fast and furious,” says the interior designer Brian J. McCarthy. “You don’t have many dealers like Gerard, who do the study and tell you why a piece is really good and precisely what about it makes it special.”

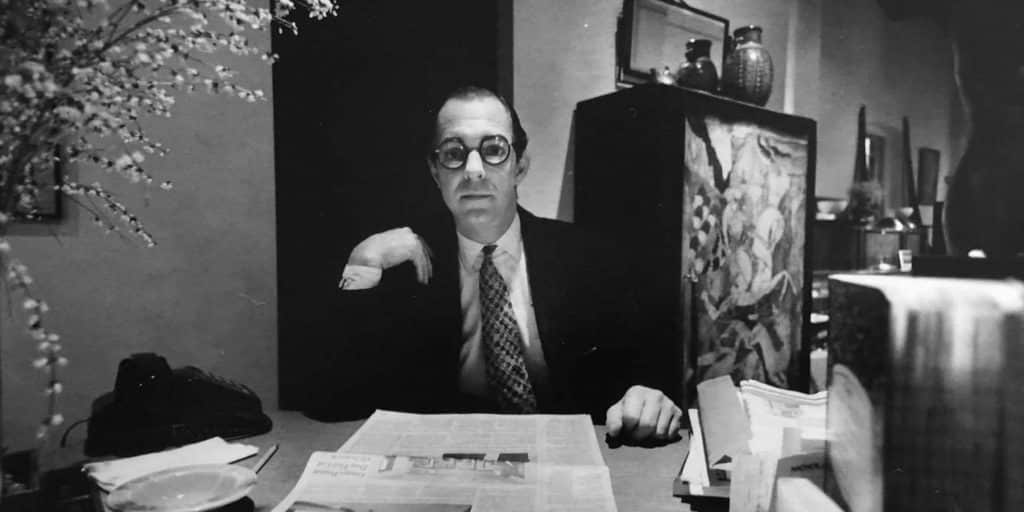

Quite apart from his expertise — for years he served as a vetter at TEFAF, Modernism, the Haughton fairs and the Winter Antiques Show — Widdershoven had a winning personality. He dressed impeccably and was noted for his bowtie and the twinkle in his eye. He was charming, debonair, gracious, gentle and kind.

“I can’t remember when I didn’t know him,” says Barbara Deisroth, who headed the 20th-century decorative arts department at Sotheby’s for three decades before becoming a private art and design adviser in 2003. “We started at the same time. I’d see him at the shop and at the sales. We traveled to fairs in Abu Dhabi and Dubai together. We would vet together.

“He was the only decorative arts dealer who threw cocktail parties,” Deisroth continues. “Years ago, he was so angry that Sotheby’s didn’t give me a going-away send-off that he insisted on hosting a party for me. He asked for a list of my friends, and I gave him twenty names. ‘Twenty people don’t make a party!’ he said. When I arrived, there were two hundred people there. It was like a love fest, not only for me but also for Gerard. I never heard anything bad about him. Ever.”

“Gerard had such calmness,” says Mark McDonald, a friend from the early 1980s whose gallery Fifty/50 was a block away. “He listened to you.”

“He never tried to impress you,” says McCarthy. “He was the real deal, and Maison Gerard is the real deal.”

“I spent a lot of wonderful times with him,” says restaurateur Jean Denoyer, a client, a fellow student of Art Deco and an avid collector of Ruhlmann and Leleu. “I think we probably learned from each other.”

“He was one of a kind, a wonderful, sweet man,” says New York designer Victoria Hagan. “Everyone knows what an incredible eye he had — for large scale pieces down to the smallest vase — but his heart was what brought all of us in.”

And he had a sense of humor. “I’ll never forget when I had my twins,” Hagan adds. “Gerard called me — ‘Victoria, how chic! You had a pair!’ ”

The New York designer Marshall Watson says he goes to Maison Gerard at the end of every major job, looking for (and finding) “that final piece that puts the project over the top.” Watson calls the gallery “a treasure trove of the very best, and notes that Widdershoven’s “pieces had flawless proportions, original in every way, and his educated analysis of each piece lent credence to its value — and the price tag that accompanied it.”

“Gerard was a gentleman in all senses of the word,” says Manhattan designer Phillip Thomas. “The first time I met him, I was instantly drawn to the passion he had for his work. He imbued the world of antiques with a whole new energy I hadn’t experienced before.”

Above all, Widdershoven was honest. “Already acknowledged for his unparalleled taste, Gerard was equally esteemed for his unquestionable integrity,” says the New York entrepreneur Deborah Miller, who over the years bought several pieces from the gallery. “And he was a skilled mentor to Benoist.”

He also changed the nature of vetting at fairs. “He helped transform vetting from an often contentious and disputatious occurrence into a collegial and fair process where dealers and vetters, often wearing two hats, exchanged information and debated the merits of the exhibited pieces,” says Daniel Harrison, founder of the gallery H.M. Luther. Widdershoven asked tough questions but was willing to listen. Instead of argument, he built consensus. “The results were educational to all parties and highly beneficial to presenting the correct pieces, correctly described and correctly authenticated,” Harrison says.

In 1998, Gerard welcomed Drut as his partner, dubbing him “mon petit héritier.”

“Right from the start, it just happened to be the perfect fit,” Drut recalls. “There was a really healthy contrast between us. Gerard was prudent enough to steer us in the right direction. I was adventurous enough to go for the big purchase. It worked because we always had trust in each other.”

He says Widdershoven taught him this most important lesson: “If an object is not good to start with, why bother with it? This is not being an antiques dealer.”

Over the years, the gallery expanded into contemporary design, introducing new collections by Salvagni, Ayala Serfaty, Georgis & Mirgorodsky, Van der Straeten and Niamh Barry.

“Gerard immediately understood the roots of my work, and we had incredible conversations about history, design and philosophy,” says Salvagni.

“Gerard always had a stylish gallery, with great taste and panache, but it became even more sophisticated when he added contemporary work,” says New York designer Alex Papachristidis. “The first time I saw Hervé Van der Straeten was there. There is a timelessness to the gallery’s contemporary pieces that work in any classical interior.”

In 2010, Widdershoven largely retired, living in Bridgehampton, New York, with his husband, the painter Nicholas Howey. He was an avid gardener but never stopped shopping for design objects. “He was always attending tag sales, flea markets, searching eBay, going to antiques shops, looking for treasures,” Howey says. He also served on the board and was the treasurer of the Madoo Conservancy, a public garden in Sagaponack.

“In the world of dealers, there are the great ones against whom we all measure ourselves, and Gerard was the measuring stick,” says Jill Dienst, the founder of New York gallery Dienst + Dotter Antikviteter, which specializes in Swedish antiques. “He was an elegant and honorable person who inspired all of us.”