Vik Muniz at Rena Bransten Gallery

September 25, 2017Handmade: Fragments in four dimensions (large), 2017, by Vik Muniz, on view at Rena Bransten Gallery. Photo courtesy Rena Bransten Gallery

Best known for his photographs of art-historical images “drawn” in chocolate or dirt, Vik Muniz clearly has a way with materials. In his new body of work, on view through October 28 in “Vik Muniz: Handmade” at San Francisco’s Rena Bransten Gallery, he has taken a turn toward abstraction, creating a series full of trompe l’oeil trickery. Some of the works are two-dimensional prints that resemble arrangements of actual objects, while others are three-dimensional collages that, from afar, could easily be prints — strings of yarn pulled tightly across a frame to form optical illusions, strips of paper glued to a surface and blobs of air-dried clay resembling puddles of paint.

The word handmade might ground the work in the simplicity of craft, but Muniz’s compositions can’t escape their sophisticated geometric abstraction.

Erica Deeman and “Modern Spirit” at Laurence Miller Gallery

Fifth Ave. Coach Co, NYC (left), 1932, by Berenice Abbott and a 2015 work from Erica Deeman’s “Silhouettes” series (right), both on view at Laurence Miller Gallery. Photo courtesy Laurence Miller Gallery

With the 57th Street building where New York’s Laurence Miller Gallery has long resided slated for demolition, the photography specialist has relocated to a bigger space, on West 26th Street in Chelsea. The increase in square footage means the gallery can now present concurrent exhibitions of vintage and contemporary work, which is exactly what it’s doing in this inaugural presentation.

San Francisco–based photographer Erica Deeman takes center stage in one part of the gallery with “Silhouettes,” up through October 28. The show comprises recent large-scale (45-by-45-inch) black-and-white portraits of women of the African diaspora. Posing her subjects in profile and photographing them from the shoulders up, Deeman aims to evoke Victorian-era silhouettes.

The more historical component is “Modern Spirit,” also on view through October 28. This selection of 45 important images includes still lifes and landscapes, portraits and street scenes, all from the 1920s through the early 1970s. The exhibition demonstrates how the work of earlier experimental photographers like Edward Weston and Berenice Abbott influenced postwar lensmen like Robert Frank and Danny Lyon. It also shows how photography has shaped our collective memory of 20th-century America.

Jacob El Hanani at Acquavella Galleries

The Hebrew Alphabet, 2016, from Jacob El Hanani‘s “Mondrian” series, on view at Acquavella Galleries. Photo courtesy Acquavella Galleries

It can take years for Jacob El Hanani to complete one of his delicate, intensely detailed drawings, so this gathering of 13 of his canvases and 15 of his works on paper at New York’s Acquavella Galleries from October 2 to November 17 is not to be missed. To create this labor-intensive oeuvre, dating from 1975 to the present, the Moroccan-born, Israeli-raised and New York–based artist made thousands, if not millions, of tiny marks with a very sharp pen. The resulting “Linescapes” — his name for the series, as well as the title of the show — resemble a microscopic form of pointillism. The pieces conjure a range of curious abstracted forms, from rocky terrain to aerial views of cities to pulsing Op art geometries. The process may sound maddening, but the realized drawings are meditative.

Nathalie Boutté at Yossi Milo Gallery

The African Choir (Final), 2016, by Nathalie Boutté, on view at Yossi Milo Gallery. © Nathalie Boutté, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Using a laborious and distinctive process, French artist Nathalie Boutté re-creates historical photographs by assembling thousands of tiny pieces of cut Japanese paper into tidy rows. The fluffy, chenille-like collages produced in this way occupy a ground between mosaic and textile.

In their softer, lusher new state, the images, which often depict colonialist subjects, fade but are no less recognizable, suggesting newsprint or pixilation. It’s not surprising to learn that, although considered self-taught, Boutté worked as a pre-digital graphic designer.

Her 22 works in “Crossing-over” — on view at New York’s Yossi Milo Gallery through October 21 — include several that reproduce iconic pictures, like Malian photographer Seydou Keïta’s 1958 Elegant Young Man Holding a Flower, or depicting famous subjects, like Australian boxing champion Peter Jackson, one of the most photographed black celebrities of the 19th century.

Edda Renouf at Senior & Shopmaker Gallery

Light+Field 5, 2016, by Edda Renouf, on view at Senior & Shopmaker Gallery. Photo courtesy of Senior & Shopmaker

To abstract artist Edda Renouf, a piece of paper is not just a two-dimensional surface on which to apply an image — it’s a sculptural material to be subtly worked, like clay or stone. Her mark-making process is both destructive and productive, performed using pencil, ink and pastel but also with tools for incising, scoring and rubbing the surface.

For her second solo show at New York’s Senior & Shopmaker Gallery, this one up through November 4, the Paris-based American artist presents four different series of her ethereal geometric work. In one, she incises lines to cast minute shadows across the paper’s surface; in another, she delicately carves into the pigment of a pastel-covered surface. Although minimalist in form, her pieces have a powerful sensory effect, offering rich, tactile details that are best perceived in person.

Carolyn Case at Asya Geisberg Gallery

Homemade Tattoo, 2017, by Carolyn Case, on view at Asya Geisberg Gallery. Photo by Etienne Frossard, courtesy of Asya Geisberg Gallery

If Carolyn Case’s juicy, colorful abstractions look like several different surfaces converging into one, it’s not an illusion. The artist covers her canvases with veils and washes of watery paint only to sand or carve the layers away and then build them up again. High-density areas abut translucent regions, like the city meeting the sea.

For “Homemade Tattoo,” a solo show on view at New York’s Asya Geisberg Gallery through October 14, Case has increased her scale, working with oil paint on large panels. The works owe something of their brushwork and washes to mid-century gestural abstraction and Color Field painting, but the artist also hints at Pop, incorporating bits of ruled paper and tropical leaves. It’s a fresh, high-energy mix with much to keep curious eyes satisfied.

Venske & Spänle at Margaret Thatcher Projects

Helotroph Foum Squitt, 2017, photographed in a Moroccan desert, by Venske & Spänle, on view at Margaret Thatcher Projects. Photo courtesy of Margaret Thatcher Projects

Munich-based duo Julia Venske and Gregor Spänle have brought their gleaming, biomorphic white sculptures to New York’s Margaret Thatcher Projects for their fifth solo show, “Venske & Spänle — minimal invasiv,” up through October 14. Like specimens from a futuristic cabinet of curiosities, the pieces seem to occupy a state between liquid and solid, so it’s a surprise when you realize they’re hand-carved out of marble.

It’s less of a surprise to learn that the artists conceived of the works as subjects of a strangely compelling, highly imaginative sci-fi narrative. Each is a (rather cute) member of an alien species quietly invading Earth via gallery exhibitions.

Terry Thompson at George Billis Gallery

Photo courtesy of George Bills Gallery

Vying for the attention of passersby, roadside signs have long fascinated artists with their candy-wrapper colors, playful shapes, bright lights and vernacular typographies. It’s usually roaming photographers who freeze them in time, but for San Francisco realist painter Terry Thompson, they are irresistible fodder for the canvas.

Combing the streets for vintage motel, restaurant, theater and store marquees that have dodged the bulldozers of urban renewal, Thompson homes in on details — lettering, atomic-age symbols — and portrays those fragments up close.

The images gathered in “Terry Thompson: Words & Pictures,” on view at Los Angeles’s George Billis Gallery through October 21, hark back to the commercial imagery of postwar Pop, of course, but Thompson revisits the style after half a century of wear and tear, detailing chipping paint and rusting rivets. What we have are survivors from a distant era in more ways than one.

“The Art of the Platinum Print” at Peter Fetterman Gallery

Ford Model VIII Bathing Cap, New York City, 1991, by Len Prince (left) and Eyes of Allah, Islam [Muslim Woman], 1990, by Chester Higgins Jr., both on view at Peter Fetterman Gallery. Photos courtesy of Peter Fetterman Gallery

Popularized in the late 19th century, platinum printing stands out for the rich matte surfaces and delicate tonal variations that the intensely light-sensitive metal yields.

On view at Los Angeles’s Peter Fetterman Gallery through December 2, “The Art of the Platinum Print” presents a wonderful opportunity to see how some of photography’s giants, including Manuel Alverez Bravo, Horst P. Horst and Cecil Beaton, have used platinum to transform what they see, from landscapes to celebrities. One of the more stable photographic mediums, platinum resists fading better than other formats, so even the oldest images here are rich in detail.

“Bonnie and Clyde: The End” and “Collage 2oth Century Classics” at PDNB Gallery

An anonymous 1934 photograph of Bonnie and Clyde’s bullet-riddled Ford V-8 sedan with law officers in the background, on view at PDNB Gallery. Photo courtesy of PDNB Gallery

Through November 11, Dallas photography specialist PDNB Gallery is turning the spotlight on the final days of America’s most famous criminal couple. Hailing from the private collection of gallery director Burt Finger, the photos in “Bonnie & Clyde: The End” date to 1934 and show the deadly aftermath of the duo’s violent ambush by a team of lawmen led by a Texas Ranger, including their getaway car and postmortem portrait.

A concurrent exhibition, mounted in collaboration with and named for Dallas and New York design dealer Collage 20th Century Classics, contains furniture designed by some of modernism’s greats. On view is rare outdoor lighting designed in 1961 by American architect (and art collector) Philip Johnson for the grounds of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, in Fort Worth, Texas, but never put into production, as well as George Nelson’s 1946 Executive Home desk, produced by Herman Miller, which set a precedent for chic home office style in the middle of the last century.

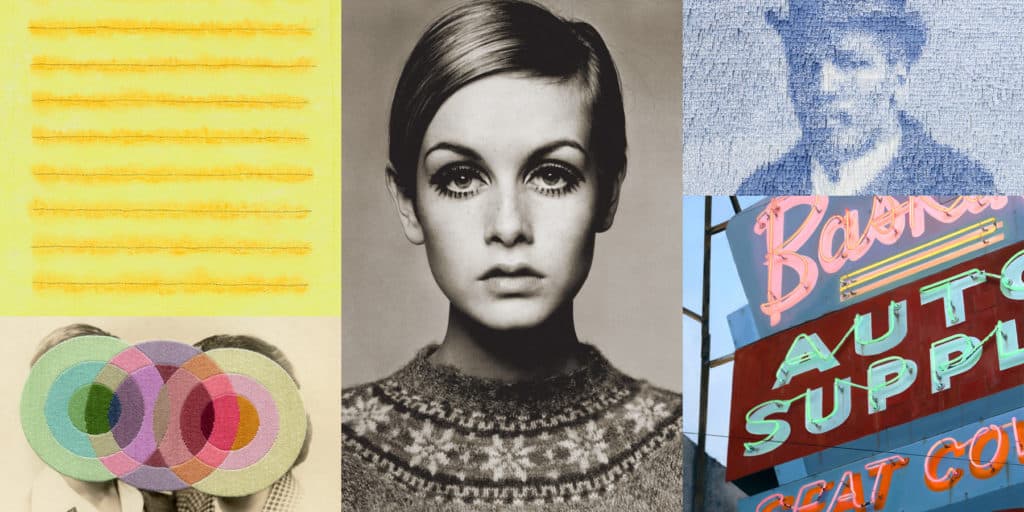

Julie Cockburn at Flowers Gallery

In the Melancholy Bubble (left) and On Reflection (right), both 2017 and by Julie Cockburn, on view at Flowers Gallery. Photos © Julie Cockburn, courtesy of Flowers Gallery

London-based artist Julie Cockburn — whose work is on view through September 30 in “All Work and No Play” at London’s Flowers Gallery — alters found portrait photographs like an irreverent doodler, but her interventions are far more sophisticated than your typical pen-drawn graffiti. With a needle and rainbow-hued assortment of thread, she overlays her unsuspecting sitters with elaborate hand-embroidered abstract patterns.

Her interventions are strangely compelling and wonderfully weird, mixing yearbook-like images from the 1940s and ’50s with veils of minimalist geometric patterns. The embroidered designs seem to have crossed over from another dimension, yet each feels tailor-made for its subject.

“In the Meeting of Rock and Sea” at Susan Eley Fine Art

Blue Green (left), 2017, by Rachel Burgess and Modern Painting (right), 2015, by Victor Honigsfeld, both on view at Susan Eley Fine Art . Photos courtesy of Susan Eley Fine Art

“In the Meeting of Rock and Sea,” up at New York’s Susan Eley Fine Art through November 2, brings together two artists who work in different mediums but share a deep affection for the rich swaths of blue that surround us. Rachel Burgess’s serene diptychs capture the sea and sky in monotypes, while Victor Honigsfeld paints ships in high seas as well as street scenes set against cloudless skies in creamy oils, recalling early American modernism.

Burgess’s prints — made by painting a piece of Plexiglas and then running it through a press with a sheet of paper atop it — have an atmospheric softness that stands in stark contrast to Honigsfeld’s energetic brushwork. The show illustrates how differently we can each see the same things.

Meg Webster at Hiram Butler Gallery

. Photo courtesy of Hiram Butler Gallery

For her third show with Houston’s Hiram Butler Gallery, artist Meg Webster is creating several of her self-contained living landscapes inside the gallery. Sculptural installations composed of soil, plants, twigs, moss and other organic materials, these ephemeral earthworks, on view through October 29, raise questions about artificiality and nature and humankind’s relationship to both art and the natural world.

Carrying the torch of 1970s Land artists like Robert Smithson, Webster arranges her natural materials into artistic, minimalist forms, and given their setting, there is no doubt that these are artworks. Yet their odors, which range from fragrant to decaying — might indicate otherwise.