August 17, 2025You’ve probably never heard of Auray, France. Most French people haven’t either. The town of nearly 15,000 inhabitants is located in Brittany, in the western part of the country, and is largely known as a gateway to the popular seaside resorts of Carnac, Quiberon and La Trinité-sur-Mer, its station being the nearest stop for the high-speed trains from Paris. In 2021, it was designated one of France’s best towns and villages by the readers of the British daily newspaper The Guardian.

I made Auray my home that same year, after three decades living in Paris, where I’d established myself as a design journalist, working as editor-at-large for AD Germany, writing books for Taschen and freelancing for publications like ELLE Decor and Introspective. The urge to leave the big city had kicked in before COVID, and I realized that Brittany was where I wanted to be after taking an idyllic birthday trip to the region and seeing a TV-news projection of the average summer temperatures throughout France in 2050. Almost the entire map featured figures above the equivalent of 100 degrees Fahrenheit, except for the top left-hand corner, where the estimate was just 77 degrees.

Auray did not disappoint. I immediately fell under the charm of its cobbled streets, half-timbered houses and picturesque river port. I also learned that its main claim to fame is that Benjamin Franklin docked there in December 1776 after sailing across the Atlantic on a diplomatic mission during the War of Independence.

I had no inkling it had a significant link to the decorative arts, as well, until the town’s best bookstore, Vent de soleil, was taken over in 2023. One of the new owners, Maël Bulot, had previously worked in a design gallery at the heart of the Carré Rive Gauche, Paris’s antiques district. “Did you know Jean Royère had a house here?” he asked.

The notion that one of France’s leading 20th-century interior designers and furniture makers had been a resident piqued my curiosity. How did an all-time great in my field end up living in my town? A quick Google search unveiled little except for the fact that his property no longer existed. It was demolished in the early 2000s. My real estate attorney’s office now stands on the site, along with two apartment blocks. Some two and a half acres of Royère’s former garden serve as a public park, although all that’s left from his time are some impressively large trees.

A visit to the municipal archives was more fruitful. Not only were its employees wonderfully eager to assist me in my hunt, but they were also the guardians of a series of extremely well-organized folders about Royère. Most of the documents pertained to his property transactions, including carefully typed letters, deeds of sale and floor plans of his home. The town had also acquired the rights to a set of images taken of the estate, known as Loch-Bihan, just before its destruction. They depict a handsome stone house and a bucolic garden planted with box hedges and hortensias.

What struck me most, however, were the interiors. I’d imagined Royère to have lived in a sleek, modernist environment, surrounded by some of his now-iconic designs, such as the Polar Bear sofa, Flaque coffee table and Liane sconce. To my mind, they are among the most beautiful pieces of furniture in existence — at once elegant and playful, wonderfully original yet rooted in classical tradition.

All of them are produced today by the furniture atelier Royère, founded in 2019 by Vladimir Markovic, the nephew of Royère’s lifelong partner, Micha Djordjevic, who inherited Royère’s artistic rights after his death, in 1981. The company’s goal is to make the furniture the way Royère did himself, with the aid of France’s finest craftspeople. “We try to be as historically accurate as we can,” says its artistic director, Jonathan Wray. “We’re super exacting in making sure the pieces fulfill the original intention.” (Royère works with 1stDibs’ private clients on a special case-by-case basis.)

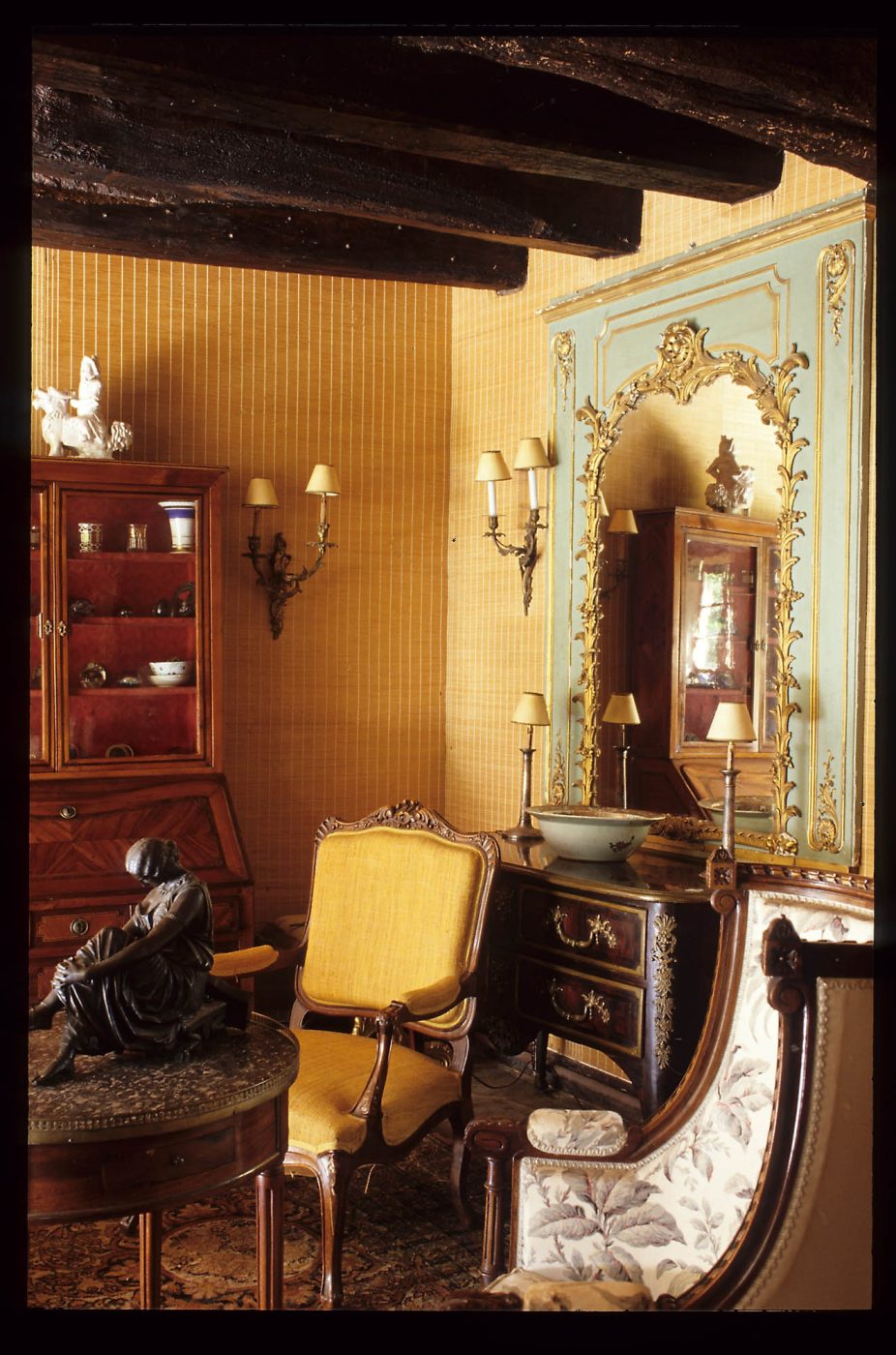

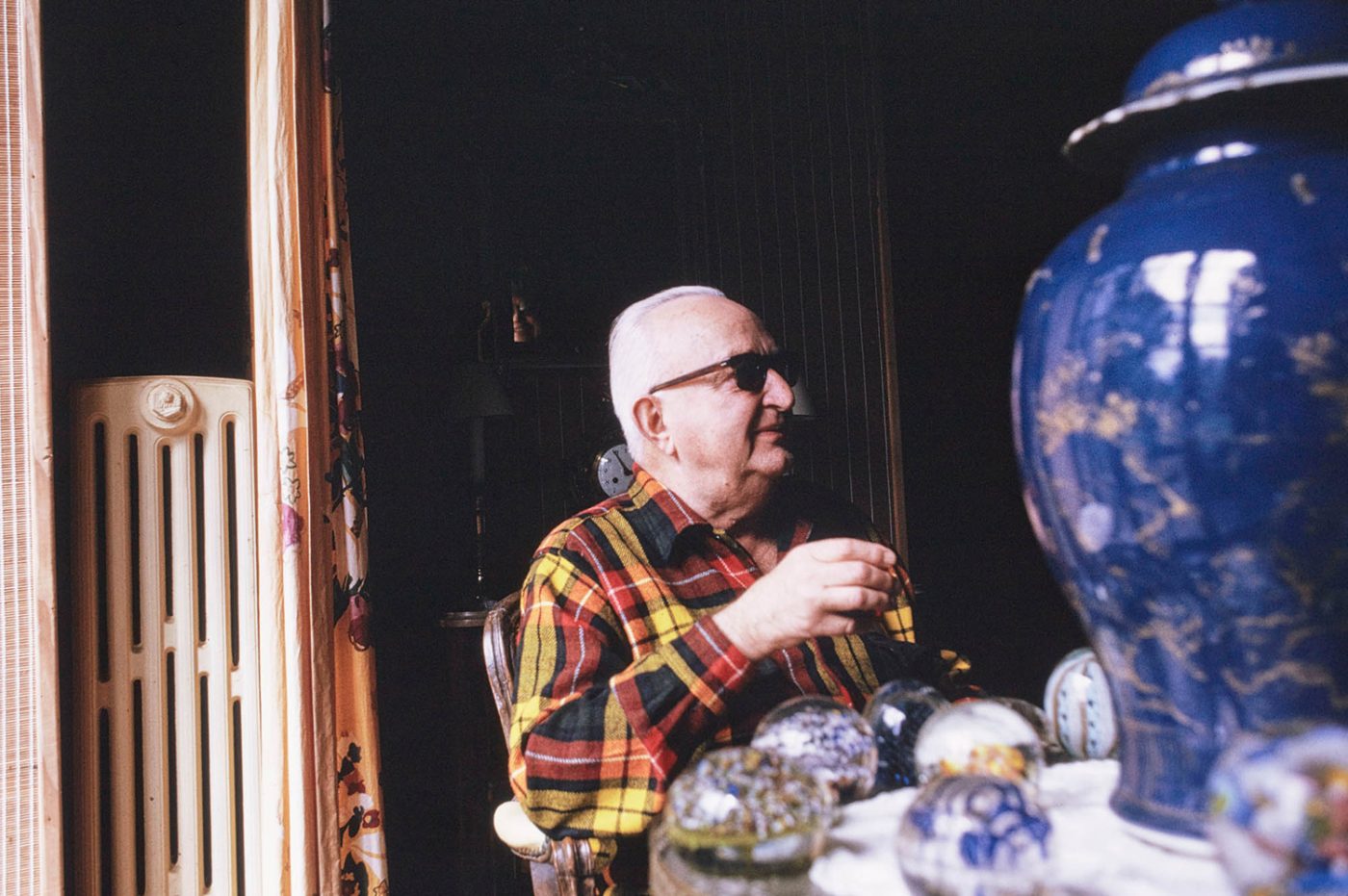

What I discovered instead was that the rooms in Royère’s Auray house were startlingly traditional and decorated mainly with family furniture. There was a large chestnut hutch in the dining room filled with Chinese porcelain, alongside Louis Philippe armchairs covered in yellow plastic. One of the bedrooms contained a marble-topped chest of drawers, on which stood a classical female bust. The choices seemed very out of sync with Royère’s assertion that he eschewed antiques.

“Like all French people, I have old items of family furniture,” he once explained to a journalist. “And I just never spend any time in the rooms they’re in. It gives me the feeling — of being a visitor in my own home.” Yet according to his niece and goddaughter Marie-Hélène Brian, he did have a slightly old-fashioned bent. “He liked mixing old and new things,” Brian told me. “Even in his apartment in Paris, there were elements that were more traditional.”

In keeping with that preference for mixing old and new, there were some typical Royère touches in Auray too. For his bedroom fireplace, he designed a black sheet-metal hood in the shape of an elongated witch’s hat. He also created a set of blue chairs, tables and lights, made from metal and rattan bound with plastic lacing, which were later exhibited as part of the 2011 show “Wrapped,” at Maison Gerard, in New York. The gallery’s owner, Benoist F. Drut, kept the lowest of the chairs for himself and has it in the sitting room of his country house upstate. “It’s a great privilege to own something that belonged to Royère himself,” he says. “I love the playfulness of the design. It’s so whimsical and a little childlike.”

Royère led an incredibly cosmopolitan life. From 1942 to his retirement, in 1971, he worked on more than a thousand projects around the world. He opened numerous galleries internationally, in locations like Lima and São Paulo, and spent six months a year abroad. He is perhaps best known for his work in the Middle East, where his clients included King Farouk of Egypt, King Hussein of Jordan and the shah of Iran. Among his commissions were the senate in Tehran, the French consulate in Alexandria and the headquarters of the Arab Bank in Baghdad. In 1970, he published a spirited memoir of his time traveling through the region, titled Harems and Gilded Feet. “He regularly recounted stories worthy of One Thousand and One Nights,” recalls his great-niece, Bernadette Vizioz. “As a child, I’d listen to him dumbstruck.”

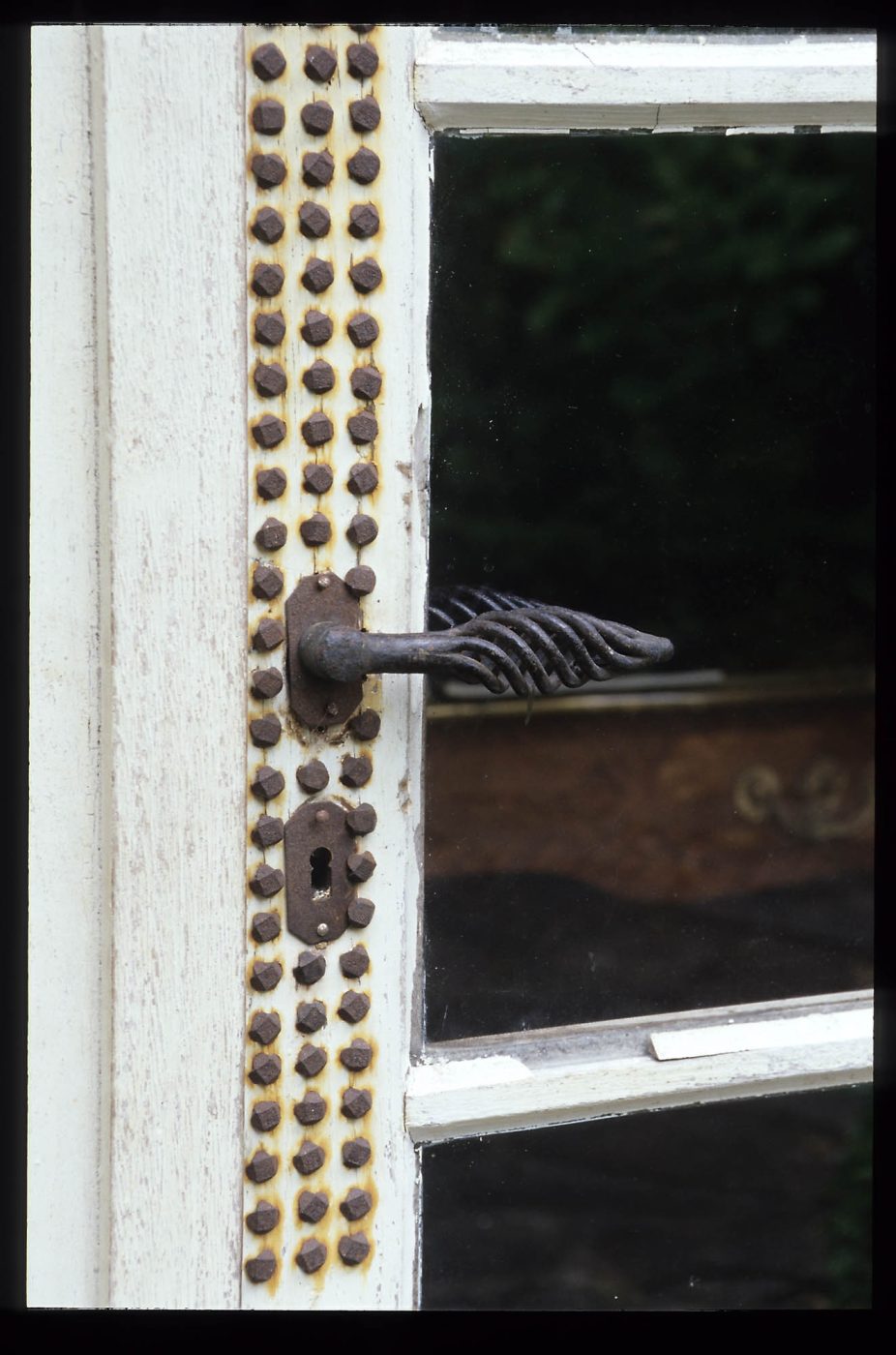

Royère integrated numerous Eastern influences into the design at Auray. The andirons in his bedroom were made from Persian stirrups, the knocker on the front door was brought back from Ispahan, and the pointed-arch openings in the garden walls were inspired by Lebanese architecture.

Throughout his life, he owned several other homes. He had an apartment on Paris’s Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, a villa on Majorca, a former fisherman’s house in Saint-Tropez and a prefabricated wooden house called La Dormerie in the Marly Forest, to the west of the French capital. He also spent several months a year in Pennsylvania, where Djordjevic worked as a college professor and where Royère himself was initially buried, in 1981 (his coffin was later transferred to Santa Barbara, where it now lies).

Yet nowhere did he feel more at home than in Brittany. His paternal grandmother’s family had had a presence in Auray since the 15th century and had acquired a significant amount of property. His father owned several farms in the region. There was also a house directly on the river in Auray that Royère planned at one time to transform into a museum. It ended up being demolished and has been replaced by a small public garden. My rummaging through the municipal archives revealed that he also developed a number of housing estates on Royère family land in Auray.

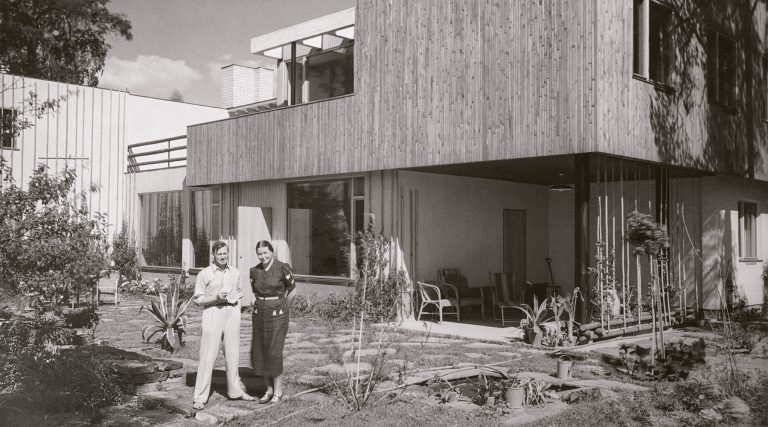

Loch-Bihan was home to several structures. The main house dated back to 1820 and was where Royère spent childhood vacations. “Inside, there was a beautiful library with paneled walls,” recalls Brian, his niece. “The other rooms didn’t have that much character.” When Royère inherited the property, upon his mother’s death in 1951, he chose not to live in that house. Instead, he rented it out to cousins and transformed a former agricultural building on the grounds into a holiday home for himself. In his building permit request, he described the structure as “an old, dilapidated building used as a hen house, stable and garage.”

It was quite modest in scale. On the ground level, there was only a sitting room, dining room and kitchen. Above were a canary-yellow bathroom and three bedrooms. One was nicknamed the Queen’s Bedroom, occupied by Royère’s friend the former Egyptian queen Farida during her regular trips to Auray. He furnished it with a four-poster bed decked with Spanish mantillas. What struck most visitors more were the abstract artworks on the walls and doors that he created using his uncle’s stamp collection. “He’d cut off the perforated edges, which meant the stamps completely lost their value,” recounts Vizioz, his great-niece.

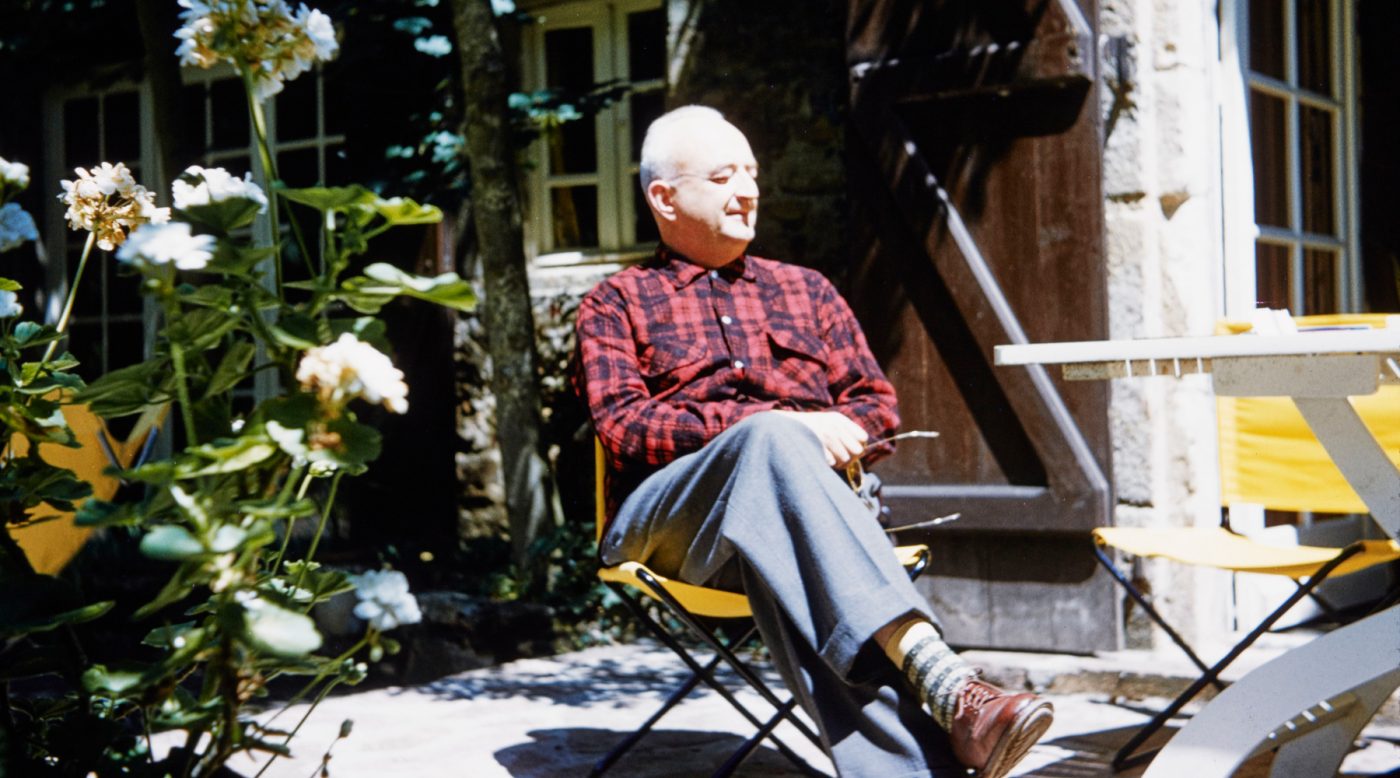

Royère designed the garden himself, planting abundant hortensias and installing a water basin with a fountain. There was also a sizable vegetable garden, as well as the tombs of his parents, who both died at Loch-Bihan. When in residence, he would spend much of his time within the grounds. “Even though it was right in the heart of town, you felt like you were in another world,” says his attorney Philippe Paul, who was invited to lunch there in the late 1970s. “You couldn’t hear a thing.”

After a visit in August 1959, Markovic’s mother, Jelena Markovic, noted in her diary that Royère entertained profusely at Loch-Bihan, serving caviar, Cinzano and stuffed peppers to guests. “He was a bon vivant,” says Brian. “He always had beautiful tableware and cutlery engraved with the family arms.”

The importance of Loch-Bihan to him cannot be overstated. “It was not a property like any other,” remarks Parisian dealer and Royère specialist, Patrick Seguin. “It’s very moving to witness a certain restraint in its decoration, which reflects his attachment to his family history.” Adds Brian, “It was part of him, it was his roots. He retained a deep love of Brittany right to the end of his life.”

What an absolute shame then that the property was not preserved after his death. After months of researching Royère’s Auray life, I can’t help feeling outraged that it was sold between 2003 and 2005 to a property developer who was allowed to tear it down. But back then, Royère’s work had not been completely rediscovered, and his sofas and armchairs were not yet making millions at auction. My discussions with the town’s archivists revealed that they share my regrets. They started organizing guided Royère tours a few years ago, but they stopped because there’s so little still standing for visitors to see.

I’d love nothing more than to bring a bit of the master back to Auray, if only temporarily. Once the municipal authorities return from their summer break, I’m hoping to explore the possibility of organizing a Royère exhibition in the place that captured his heart — and now has mine too.