February 23, 2025What makes something a classic? It’s a question that Barbara Corti has wrestled with a lot. Since 2023, when she was named chief creative officer for the Italian lighting maker Flos, Corti has sifted through more than 60 years of the company’s products to come up with a list of its most enduring designs.

“The moment I started in my new role at Flos, I began analyzing our archive,” Corti said in a recent interview. “I started to question why some of our lamps have ‘aged’ better than others — why some have become icons and others have surrendered their identity to the spirit of the time they were made.” In the end, she tapped a dozen standouts.

Under the art direction of Omar Sosa, of Apartamento Studios, the lamps that made the final cut were stylishly photographed by Catalan visual artist Daniel Riera in settings befitting their icon status — Milanese palazzi designed by such architects as Gio Ponti and Alberto Rosselli.

Many of the lamps that appear on Corti’s list will be readily recognizable to design aficionados — although they may not realize the fixtures were all made by the same company. Since its founding, in 1962, Flos (which takes its name from the Latin word for flower) has collaborated with such mid-century masters as Gino Sarfatti and brothers Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, as well as present-day talents like Philippe Starck, Jasper Morrison, Patricia Urquiola and Antonio Citterio, and it was pivotal in bringing progressive European lighting to an international audience.

Now in its seventh decade, the company remains innovative, nurturing new designs, materials and technologies, while continuing to offer the classic lamps that have become part of the global design lexicon. “This project has been an important exercise in reexamining our legacy,” Corti said, “and has made me realize the power of these objects.”

Luminator

While much of mid-century modernism’s popularity today seems rooted in nostalgia, many Flos designs from that period are still surprisingly fresh — seeming to look forward, not back.

First produced by Gilardi & Barzaghi in 1954, Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni’s Luminator became a part of the Flos catalogue when the company was established, in 1962.

The lamp remains a radical design, reimagining the classic torchiere stripped down to the skeletal components of tripod, stem and bulb. (In the designers’ bid to eliminate anything extraneous, they even allowed the cord to dangle cavalierly from the stem.) Its lithe form and adaptability — one could well imagine it in an urban loft or a Venetian palazzo — ensure the lamp’s continued longevity.

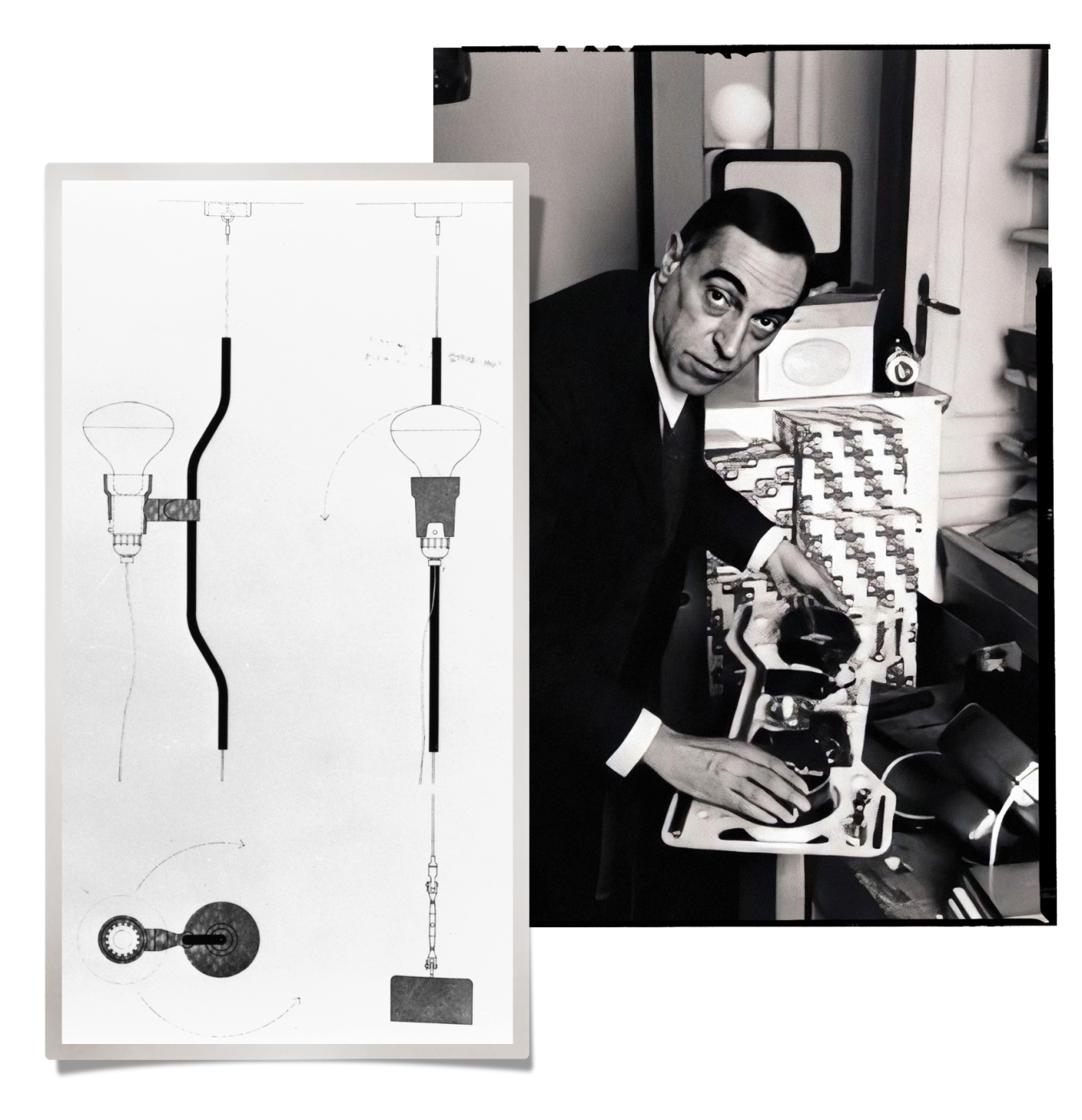

2097

Trained as an engineer, Gino Sarfatti was not only prolific (he created more than 600 pieces for his lighting firm, Arteluce, which Flos acquired in 1972) but also disciplined, eschewing fanciful product names in favor of a strict numbering system that categorized his pieces by type.

His 2097 chandelier, designed in 1958, turned technology into a source of beauty long before such conceits were common. Instead of hiding the bulbs’ wiring inside the piece’s armature, Sarfatti left it exposed, allowing the wires’ sinuous lines to mimic the elegant arms of a traditional chandelier.

Gatto

Flos was a hit right out of the gate, thanks in large part to the success of its cocoon lights, which were fashioned from metal armatures sprayed with a polymer coating as they rotated, producing a seamless translucent skin that clung to the ribs.

Designed by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, the fixtures were a natural successor to George Nelson’s Bubble lamps and Isamu Noguchi’s Akari lamps of the 1950s. But the Castiglionis took the idea to another level, with more elaborate shapes that stressed the tension between armature and coating.

Like the cat for which it is named, the 1960 Gatto table lamp can be seen as a demure companion or a commanding presence — it all depends on how you approach it.

Taraxacum

The Castiglionis’ technique of spraying polymer onto a rotating metal frame was also applied to pendants, like the 1960 Taraxacum, which gets its name from the Latin word for dandelion.

If the inspiration is humble, the fixture is anything but, its irregular shape posing a provocative counterpoint to the more subdued, symmetrical spheres of Noguchi and Nelson. Those designers downplayed the framework in favor of the skin. Here, the armature looks like it’s struggling to break free, adding a sense of intrigue to the design.

Arco

Has a lighting fixture ever signified power or success more readily than the Arco lamp? From the James Bond film Diamonds Are Forever to the TV drama Mad Men, it has served as a kind of cultural shorthand for urban sophistication (or urban warfare, commandeered as a weapon in the movie What’s Up, Doc?).

In production since 1962, the Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni creation features a spun-aluminum reflector supported by a cantilevered curved stem affixed to a block of Carrara marble. Ingeniously, it provides overhead illumination without the need to install an overhead light. Once very much of its time, the Arco now feels timeless.

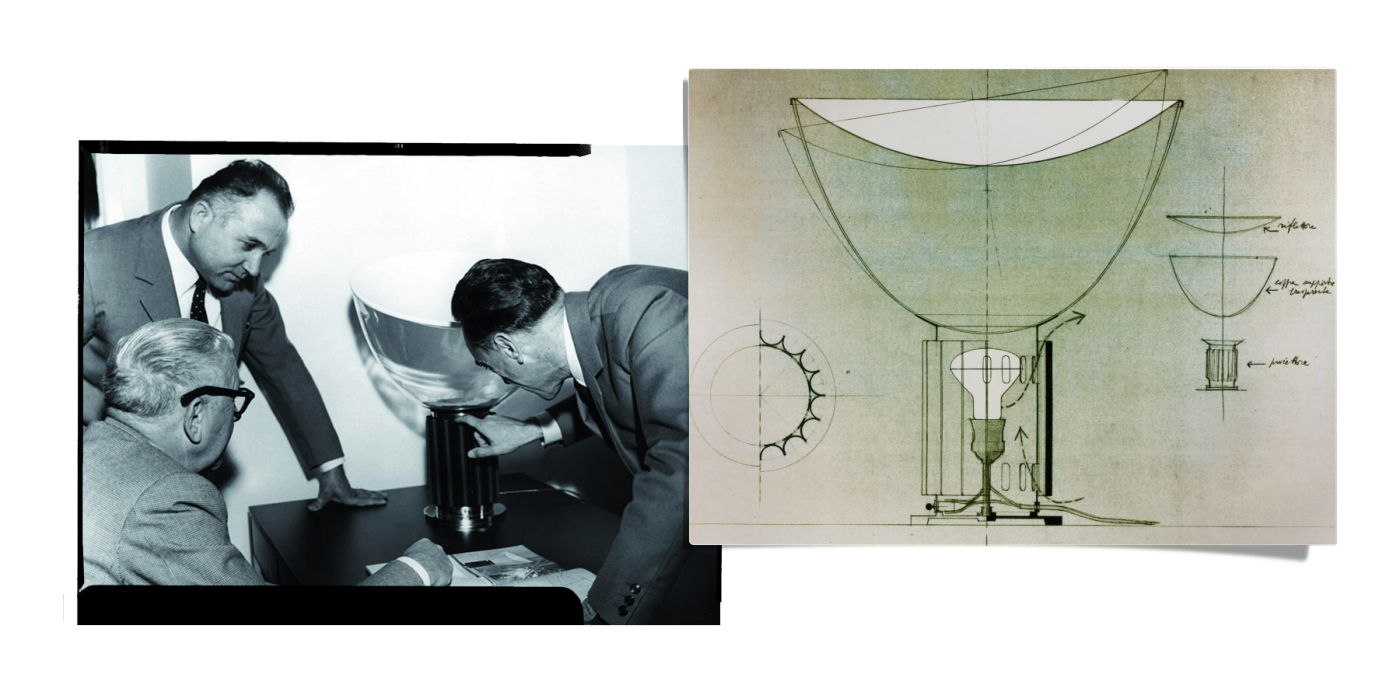

Taccia

Designed by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni in the late 1950s, and introduced by Flos in 1962, the Taccia table lamp is simple yet counterintuitive. What appears to be an uplight is actually a downlight.

The fluted aluminum base hides the light source and initially (in the piece’s original incandescent form) provided ventilation for the bulb within. Light from the bulb bounces off a concave aluminum reflector resting atop a clear, bowl-shaped diffuser, illuminating the surface below; the angle of the light can be adjusted by simply tilting the diffuser.

Of course, there are more straightforward ways to light a tabletop. On the other hand, a sedan and a sports car will both get you to the grocery store. But the sports car will be more fun.

Snoopy

The Broadway musical You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown premiered in 1967. That same year, another creation related to the popular Peanuts comic strip made its debut: Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni’s playful Snoopy lamp.

While its resemblance to the strip’s beloved beagle is debatable, the lamp’s charm is not. The angled marble base supports an oblong enameled shade that reflects light through a glass diffuser, evenly illuminating the tabletop below.

With its saucy stance and choice of shade colors, the piece transforms the prosaic desk lamp into something worth celebrating — or maybe even singing about.

Biagio

Its shine may be understated, but the Biagio still manages to light up a room. Carved from a single piece of Carrara marble, this 1968 design by architect Tobia Scarpa is as much a sculpture as a lamp, its form recalling the coiled curves of a seashell.

When illuminated, the stone casts a glow that reveals the veining within — an act of transformation that remains as thrilling today as it was nearly 60 years ago.

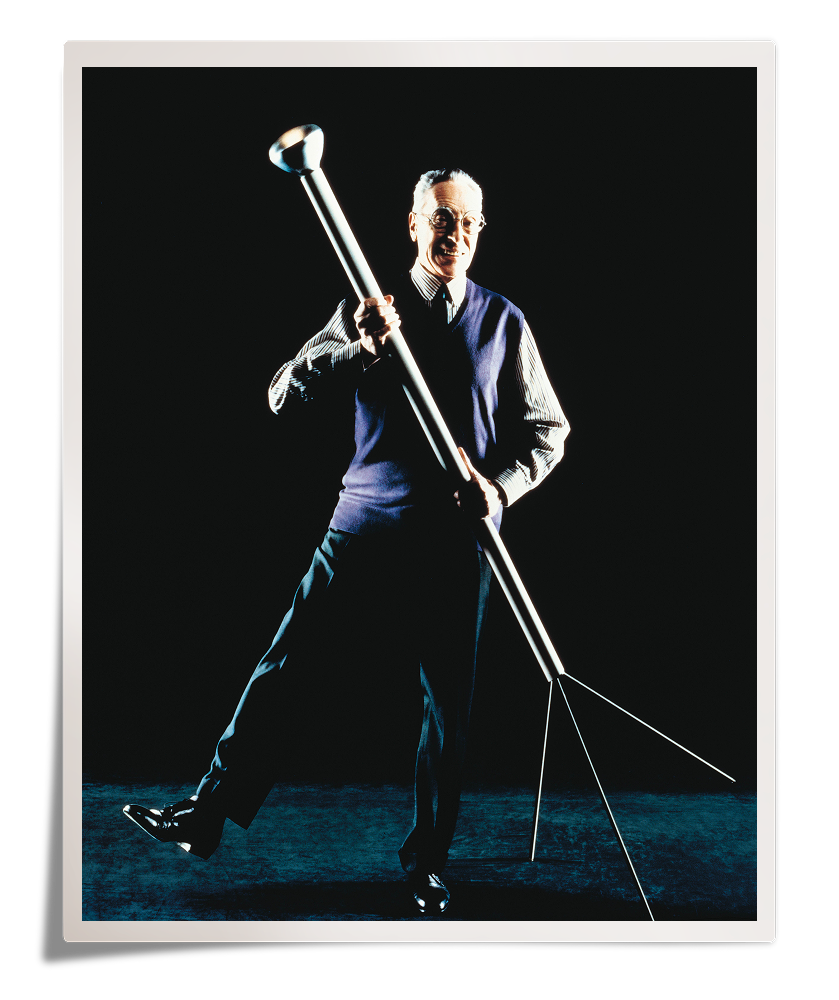

Parentesi

The Parentesi lamp has been a success since its launch, in 1971, thanks to its simplicity, utility and beauty.

Conceived by automobile and product designer Pio Manzù and completed by Achille Castiglioni following Manzù’s death, the design consists of a taut steel cable — suspended from the ceiling and anchored by a counterweight on the floor — along which glides an adjustable spotlight affixed to a tube shaped like the titular parenthesis.

As the spotlight is slid up and down the cable, it’s held in place by friction, focusing light where it’s needed in a sublime synthesis of function and aesthetics.

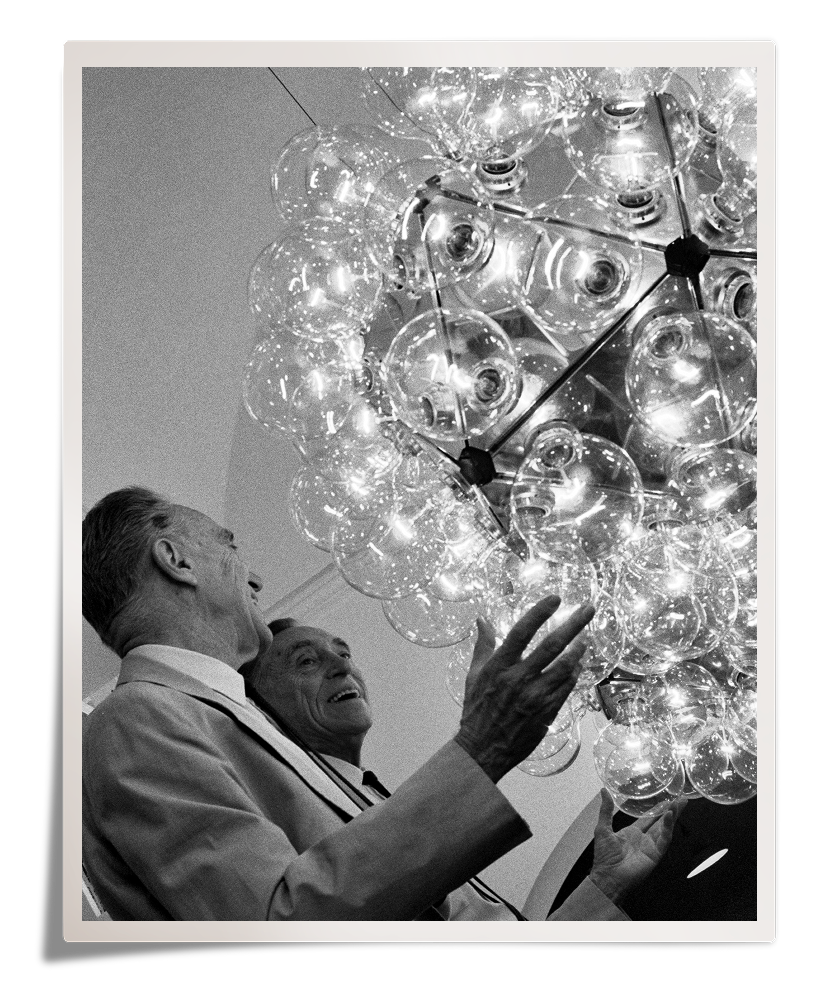

Taraxacum 88

More than a quarter century after introducing the Taraxacum, Achille Castiglioni revisited the concept with the Taraxacum 88. Although, like the original, it takes its inspiration from the dandelion, the 1988 iteration doesn’t keep its light source under wraps. Sixty clear bulbs spring from a shiny aluminum core, recalling the seed heads on its namesake flower and providing direct as well as reflected light.

Grand in scale and presence (Castiglioni envisioned it for public spaces and rooms that needed a lot of illumination), the fixture is an extroverted reinterpretation of its more introverted predecessor, turning lighting into a spectacle.

Glo-Ball

Like a full moon lazing above the horizon, the Glo-Ball is both a thing of beauty and easy to overlook. Created by English designer Jasper Morrison and introduced in 1998, it boasts simple lines that belie the complexity of its components — most notably a diffuser made from acid-etched, hand-blown opaline glass that disperses the fixture’s milky-white light evenly throughout a room.

Available as a pendant, floor lamp, sconce or ceiling light, the Glo-Ball remains a design staple, admired for its purity of form and ability to brighten an interior without stealing focus.

IC Light

Inspired by the way champion juggler Tony Duncan balanced spinning spheres on his arm and hand, London-based Cypriot designer Michael Anastassiades created the IC Light, which Flos introduced in 2014. (The name refers to the controversial “identity codes” that police in the United Kingdom use to communicate a person’s perceived ethnicity; the design may suggest the balancing act people perform as they navigate one or more identities.)

Available in six different configurations, the design features an opaline glass diffuser balanced on a slim metal rod, apparently in defiance of gravity and with little connection between the two. It’s a tricky sleight of hand to pull off, but the resulting fixtures have an elemental allure that makes them exceptional additions to any setting — in other words, iconic.