March 30, 2015Seattle architect Tom Kundig creates serene, sophisticated buildings that elevate humble materials and celebrate a connection to nature (photo by Richard Darbonne). Top: Kundig’s Rolling Huts project, 2007, consists of six mobile, modernist bungalows in a former RV park (photo by Derek Pirozzi).

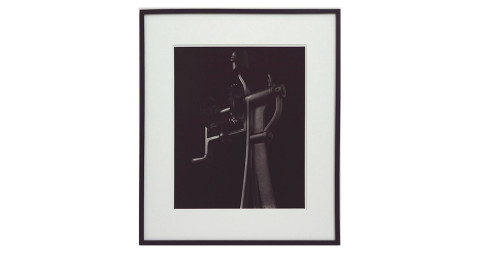

Growing up in Spokane, Washington, Tom Kundig was fascinated by the humble buildings that dotted the eastern part of his home state and the southern stretches of neighboring Idaho: silos, barns, fishing cabins, mining camps and sawmills. The houses he designs today recall those same un-architected buildings. Kundig builds with rough wood, rusty metal and concrete, into which he inserts oversized windows and doors, some of which open in unexpected ways, thanks to custom mechanisms that can only be described as gizmos.

Like a jazz musician riffing in steel and cement, Kundig sometimes doesn’t know until a house is being built what problems will arise, much less how he’ll solve them. But it is those improvised solutions, often involving the gizmos that have become one of his trademarks, that give his houses their striking individuality and haunting beauty. (Several of his most notable buildings have been brought together in a forthcoming book, Tom Kundig: Works, slated for an October release by Princeton Architectural Press.)

It’s no wonder clients occasionally come to Kundig with photos of his past projects — gorgeous images from books and magazines — and ask him to “combine this one with that one.” Kundig declines; he would never take a solution that arose at one site and transplant it to another. But if the clients are game, he may give them something even better.

A closer look at one of the Rolling Huts reveals that each consists of a simple, steel-clad box set on a steel-and-wood platform. The minimalist materials used inside include cork for the floors and plywood for the walls and ceiling. Photo by Derek Pirozzi

Kundig clients don’t have to be rich (some of his best projects have been tiny cabins), but they do have to be open to improvisation — as a mountaineer, Kundig learned long ago that the journey is as important as the destination — and even imperfection. If he senses that a potential client wants something with a little more polish than he’s likely to provide, he may send them down the hall to see Jim Olson, his partner in the 125-person Seattle firm Olson Kundig. Olson, who founded the firm in 1967, designs houses of extraordinary elegance, usually for art collectors. The two of them have worked together for nearly 30 years — and although their respective styles are distinctive, each has influenced the other, with Olson’s signature style giving up a bit of luster and Kundig’s taking on a quiet sheen.

It might not be too much of a stretch to say that, while Olson’s houses are designed around art (even those in spectacular settings), Kundig’s abodes are designed around nature, embracing both its opportunities and its challenges. His Chicken Point Cabin, built in northern Idaho in 2002, features a 20-by-30-foot window wall that opens with a hand-crank that seems to ratchet the house closer to the nearby lake with every turn. Another residence, on one of Washington State’s San Juan Islands, was built directly into a rock outcropping that comprises many of its walls. With its grass-covered roof, it sits — quite literally — between a rock and a soft place.

Like a jazz musician riffing in steel and cement, Kundig sometimes doesn’t know until a house is being built what problems will arise, much less how he’ll solve them.

Built into an outcropping on one of Washington’s San Juan Islands in 2010, a house known as the Pierre — French for “stone” — incorporates rock from the site in a variety of ways, not least of all as an element of the concrete flooring. The dining room console seen here is by Paul Evans. Photo by Benjamin Benschneider

One of Kundig’s most simpatico clients was Jan McFarland Cox, an artist and designer who came to him more than a decade ago with the idea of building a retreat in Idaho’s rugged high desert. To Kundig, the landscape wasn’t just familiar — it was, he says, “in my soul.” He began sketching a simple box, with a living-dining room on one level and a loft bedroom above. But Cox had trouble selling her old house, which caused delays. Those delays, at a time of rising construction costs, meant Kundig had to simplify the design, and simplify it again, until the house was reduced to elemental forms. Not surprisingly, the resulting gray cinder-block box, with its extraordinary clarity and compelling smooth-rough mix, became one of his best-known (and most photographed) houses.

The Cox saga reminded Kundig that “one of the most important skills for an architect — and perhaps the least-appreciated — is knowing what to eliminate.” If you have too many ideas, Kundig says, “you might want to focus on one of them, and store the others away in a memory bank, hoping they return to you” when the right project comes along.

These days, Kundig has plenty of chances to use his stored-away ideas. He is busy with houses in Los Angeles, New York, Kauai, Jackson Hole, Geneva, Sydney and Salt Lake City, a “teeny hut” on the side of a mountain in Rio de Janeiro and a “little teak house” on Costa Rica’s Nicoya Peninsula. Most of the projects tend to be between 2,500 and 4,500 square feet — placing them near the average size for new homes in the U.S. — but a few are considerably larger. The sprawling ones, he says, are often for extended families, and are built to house several generations that will live together under one roof: “a trend of the future that actually looks to the past.”

At Mission Hill, Kundig used board-formed concrete for below-grade elements — like this staircase leading from the winery’s central plaza to its barrel-aging cellars — and precast concrete for above-ground structures, including the 85-foot bell tower. Photo by Paul Warchol

While Kundig is best known for designing houses, he is also finding that his aesthetic, drawn in part from industrial buildings, can work on a larger scale. On a hilltop overlooking British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley, he created a small cluster of buildings for the Mission Hills Winery that includes tasting rooms, restaurants and a theater. But the architect’s favorite part of the project may be the cellars, where he got to shape vaulted spaces (suggesting wine barrels writ large) of poured concrete. Since then, he has designed an addition to the Tacoma Art Museum, southwest of Seattle, where sunscreens move on metal tracks that recall the railroads that put the town on the map, and he is currently working on a natural history and culture museum for the University of Washington (where he received his undergraduate and graduate degrees), which will be as formally simple as a one-story factory building. He is also renovating a warehouse in Seattle for the vintner Charles Smith — a high-end winery right in the city center — and designing a 50-room “spa hotel” in the Austrian alps that can only be reached by gondola. (Now that’s a gizmo.) As for smaller-scale projects, he has created a line of hardware, the Tom Kundig Collection, which includes pulls, rollers, door knockers and knobs.

“So much architecture these days is overdone and overworked,” says Kundig, adding that he isn’t immune to the temptation to take things too far. But when he can, he edits out indulgences. “The closer a buildings sticks to its baseline idea,” he says, “the better it will be.”