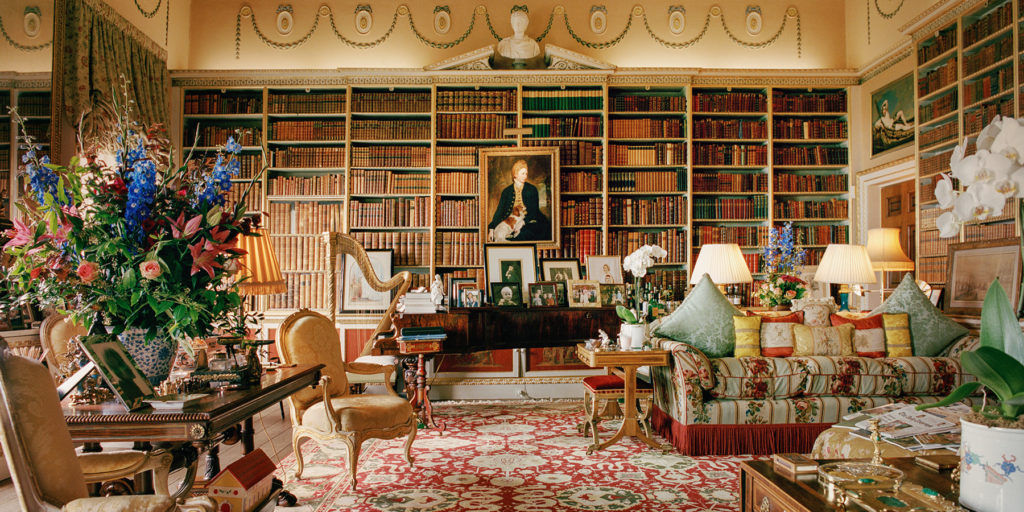

In Great House, Modern Aristocrats , writer James Reginato worked with photographer — and fellow Vanity Fair contributor — Jonathan Becker to take readers inside the homes of highly acquisitive grandees in England, Scotland and Ireland, including Oxfordshire’s Blenheim Palace (above). Top: The large library at Goodwood House, in West Sussex, family seat of the Dukes of Richmond. Photos by Jonathan Becker, courtesy of Rizzoli, unless otherwise noted

In the course of researching my new book, Great Houses, Modern Aristocrats (Rizzoli), I visited many stately houses in England, Scotland and Ireland that have been lived in by the same families for hundreds of years. I learned in my travels that no matter what the century, great collectors have always been insatiable. My definition of what constitutes “contemporary” art certainly expanded, too.

Old Masters were once fresh goods, of course, and it was fascinating to see so many of them hanging on the very same walls where they’d landed upon leaving the artists’ studios; some masterpieces were even produced in situ.

In 1759–60, for example, the 3rd Duke of Richmond invited George Stubbs to Goodwood House — his glorious seat in West Sussex, which had been in the family since 1697 — to paint three views of the estate. It was the artist’s first major commission. As soon as the paint was dry, the pictures were hung in the front hall, and there they have remained. Two magnificent views of the Thames by Canaletto, a commission from the 2nd Duke of Richmond in 1747, hang nearby.

Continuing to abound in such prizes, Goodwood today serves as home to Charles Gordon-Lennox, Earl of March — who is in line to become the 11th Duke of Richmond — his wife, Janet; and their five children.

At Lismore Castle, a multi-turreted fortress built in 1185 on a high cliff above the River Blackwater in County Waterford, Ireland, I was somewhat startled to see an installation of work by the late Jason Rhoades, which used neon signs to spell out slang expressions for female genitalia. What would some of the former owners of the property, who included Sir Walter Raleigh, make of such an artwork?

As part of their restoration of Luggala — a shooting lodge turned mansion in Ireland’s County Wicklow — designer Mlinaric and his colleague Amanda Douglass selected a wallpaper called Gothic Lily, which was designed by A.W.N. Pugin, a 19th-century proponent of the Gothic Revival style in which the lodge as a whole is decorated.

William Cavendish, Earl of Burlington, the castle’s current occupant, is aware that displaying the piece in this setting might arouse some controversy. But he takes the long view. After all, he has 500 years of art collecting under his family belt. Born in 1969, he is heir to his father, the 12th Duke of Devonshire, and so will one day inherit the fabulous Chatsworth, which his ancestors have been stocking with treasures since 1549.

Through family lore, he is familiar with how the 6th Duke of Devonshire shocked his contemporaries in the 1820s by purchasing freshly carved sculptures of minimally clothed figures from the Rome studio of Antonio Canova that he then had installed in his Derbyshire palace. Centuries later, William’s celebrated grandmother, Debo, née Mitford, wife of the 11th Duke, raised eyebrows in her social circles when she became an early patron of Lucian Freud.

So when William and his wife, Laura, decided to turn a derelict wing of Lismore into an exhibition space for contemporary art, calling it Lismore Castle Arts, he was prepared for skeptics. He put his own spin on his clan’s long tradition of collecting and connoisseurship. “I wanted to do something that was a bit more ephemeral, not so acquisitive,” he told me.

To that end, in 2007 he mounted a show in collaboration with another great collecting family, albeit one newer to the game than the Cavendishes: the Rubells of Miami, led by husband and wife Don and Mera.

No matter what the century, great collectors have always been insatiable.

Today, Luggala is occupied by the Honourable Garech Browne, who favors a purple tweed suit and has been dubbed by Reginato Ireland’s last dandy. Here, a Victorian bed in a Luggala guest room is hung with purple silk, continuing the lavender theme.

For the exhibition, “Titled/Untitled,” the Rubells selected pieces from the Devonshire holdings — including portraits by Anthony van Dyck, Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough — while Lord Burlington chose from the Rubell Collection, picking video works by Hernan Bas, for example.

“My family began our collection fifty years ago, and his began five hundred years ago,” remarks Mera. “But I was so impressed by how forward-thinking he is. He is a very contemporary person. And at the same time, he is determined to understand and appreciate the past.”

It is quite an accomplishment for any house, especially an establishment of great scale, to remain in the hands of direct descendants for centuries. How is it that certain families have kept going so long and so well under the same roof? As I came to see, none of them are stuck in time.

Norfolk’s Houghton Hall, built in 1722 by Sir Robert Walpole, is considered one of the most perfect examples of Palladian architecture, with its stunning interiors by William Kent and staggering assortment of pictures by William Hogarth, Gainsborough and Jacques-Louis David, among others. Clearly, Walpole’s heirs replenished the collection well after representatives of Catherine the Great swept in in 1779, purchased en bloc 204 masterpieces and shipped them to St. Petersburg, where they formed the core of the Hermitage collection.

The conservatory at Dudley House overlooks Hyde Park. When Queen Elizabeth II visited Sheikh Hamad here after he restored and renovated the building, she is said to have remarked, “This place makes Buckingham Palace look rather dull.”

David George Philip Cholmondeley, the 7th Marquis of Cholmondeley, inherited the 106-room, 4,000-acre estate in 1990 and has turned the grounds into one of the most exciting arenas for contemporary art in England. Having commissioned a “Skyspace” in 2000 from James Turrell, he brought the artist back in 2015 to create a site-specific light work that illuminated the entire west facade of Houghton Hall and that was part of a major exhibition of Turrell’s work mounted at the house.

Few dynasties have excelled at the collecting game like the Rothschilds. Ferdinand, the 1st Baron Rothschild, crammed Waddesdon Manor, a stupendous neo–French Renaissance château in Buckinghamshire completed in 1883, with an Aladdin’s cave–worthy assortment of Sèvres porcelain, Renaissance gold and jewels, furniture from the reigns of the Louis, carpets, Dutch Old Masters and 18th-century English portraits. His famously acquisitive relatives were engaged in similar pursuits across Europe, building and furnishing 44 great houses during the 19th century.

“Inevitably, they liked the same things. So they did compete from time to time. But sometimes they hunted as a pack. The Rothschilds would buy whole collections, then split them up among themselves,” says Jacob, the 4th Baron Rothschild, who has watched over Waddesdon since 1988.

Even though there is now nary a square foot of space left inside the house without some gem occupying it, Jacob has continued the great family tradition, making such stellar acquisitions as A Boy Building a House of Cards by French still-life master Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin and an 80-piece dinner service commissioned by George III — a supreme example of the goldsmiths’ art.

“I’ve added quite a bit over the years. We’re doing things all the time. I’m that type,” Lord Rothschild told me. “Some of that DNA must have rubbed off on me.”

It sure did.

Or support your local bookstore.