The elegant houses of Chicago- and New York—based architect Dirk Denison are as smartly designed as they are sensitive to their clients’ needs. Above: A minimalist but layered space in a home in California’s Marin County features a Harry Bertoia sculpture (photo by Joshua McHugh). Top: The living room of an ingeniously compact Carmel, California, home is outfitted with furnishings by Charles and Ray Eames and George Nakashima (photo by David Matheson).

October 21, 2018In 2008, a magazine asked me to write about a new house in Marin County, California. The architect, Dirk Denison, was in Africa, so I went to see the residence without him. It reminded me of the Farnsworth House — Mies van der Rohe’s Plano, Illinois, tour de force — turned inside out. Here, a glass box enclosed not the residence itself but a courtyard at its center. Clearly, Denison owed a debt to Mies. But the real inspiration, I learned, was the clients’ son, Max, who was born with cerebral palsy and moves from room to room by crawling on the floor. Max needed a house that was entirely barrier-free. Denison avoided even the slightest level change, varying the heights of rooms by adjusting their ceilings, and provided built-in furniture that was stable enough for Max to pull himself up onto. Mies’s idea of universal space and Max’s need for universal access came together in an extraordinarily elegant building.

A few years later, writing a story for another magazine about small houses, I interviewed Kathy and Gary Bang, retirees who had decided to downsize. Really downsize: Kathy told me that when she and Gary, who had both lost their previous spouses, got together, they owned four residences that added up to 15,000 square feet on 150 acres. Now, they were living in a single 1,800-square-foot home on a 10th of an acre.

Denison designed the Marin Country house to accommodate the needs of a couple whose son, Max, has cerebral palsy, creating it without any barriers or level changes, which allows him to move freely from room to room. Photo by David Matheson

The structure was in Carmel, California, the seaside enclave where they decided to live full-time. But zoning regulations prevented them from enlarging their existing home there by even an inch. And so, they hired Denison to build them a much better house within the outline of the old one. Kathy described one of Denison’s many inventions: a meditation room that doubles as a guest room, with mattresses stowed beneath tatami mats. “The house is perfect for us,” she said. “It’s not a lot of space, but it’s the right space.”

Eventually, I got to know Denison, and he started telling me about his early influences. We’re the same age, and we both grew up wanting to be architects. Somehow, he realized that ambition, while I didn’t. My career as an architecture writer gives me a front row seat to what architects do. But it’s not the same as doing it.

What made it possible for Denison to follow his dream? One answer is that he grew up in Michigan surrounded by architects. I loved looking at architecture — when Paul Rudolph’s Endo Laboratories was built near my family’s house on Long Island, I was fascinated — but I don’t think I ever met an architect. Nor did it occur to me to, say, drop by Rudolph’s office.

Denison’s experience was very different. His father was an attorney; his mother, active in the Detroit arts community, was best friends with the wife of Myron Goldsmith, a partner at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill who was responsible for some of the firm’s most important projects of the 1960s and ’70s. Goldsmith took the teenaged Denison to see many of them, including Chicago’s sky-scraping John Hancock Center (1969) and Sears Tower (1973). Among the other architects Denison met were Louis Kahn (who came to his house for dinner, thanks to his enterprising mother) and Minoru Yamasaki (architect of the World Trade Center towers, whose office was near the family’s house). Denison’s parents were going to introduce him to the great Mies van der Rohe as a kind of present for his 13th birthday, but Mies died just before that could happen.

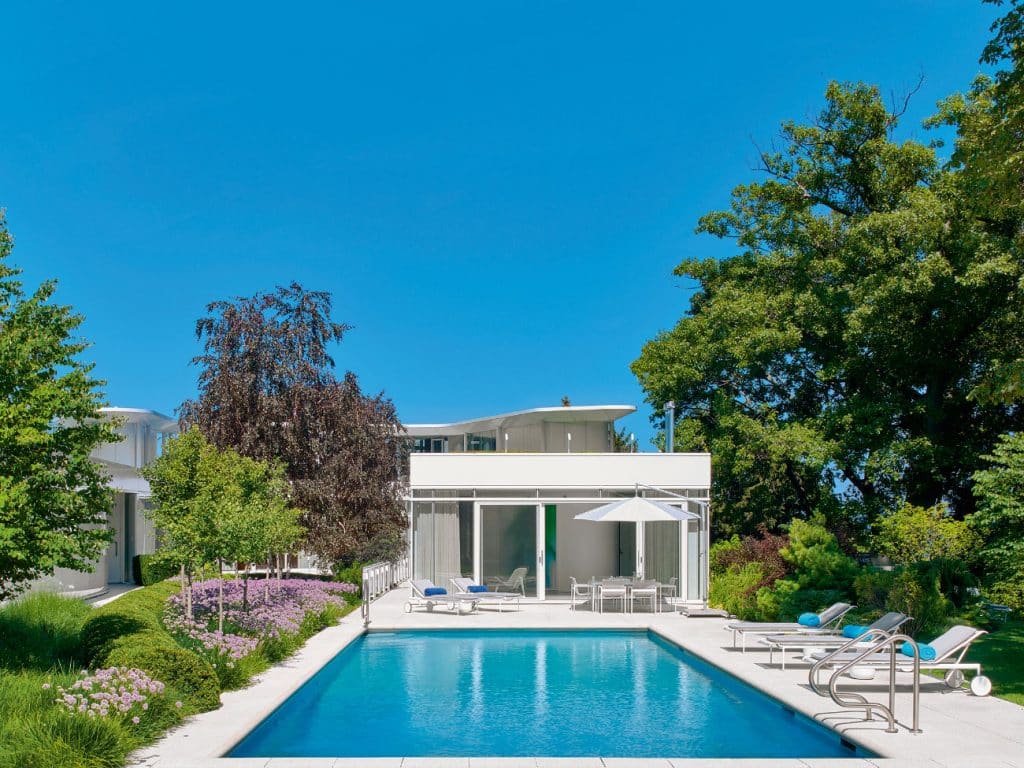

In the Chicago suburb of Winnetka, Denison built a multilevel — and multilayered — house into the sloping bank of Lake Michigan. The clients, Denison says in his new book, “wanted their own living space to be manageable in size. But they also wanted rooms for their children and grandchildren, who visit frequently. So we made two houses, one above the other.” Photo by Hedrich Blessing

After studying at the University of Michigan, Denison attended “Mies’s architecture school,” the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), in Chicago, learning a rigorously gridded form of modernism. He went on to Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, where his professors included Peter Eisenman, Daniel Libeskind and Henry Cobb, of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. Not long after he graduated, Denison began teaching at IIT, while also starting his own practice, which today has offices in Chicago and New York. Although he is best known for his houses, he has designed many other kinds of buildings, including restaurants, offices and a forthcoming dormitory at IIT, where he is still on the faculty.

A couple of years after we met, Denison asked if I would work with him on a book about his residential projects. I already knew that his early experiences with architects and architecture were more interesting than anything I could say about his buildings, so I proposed that the text be a Q&A — me interviewing him about his life and his career. The result is the just-published Dirk Denison: 10 Houses (Actar).

A key fact that emerged as we collaborated on the volume was that Denison grew up liking the work of many different architects, ranging from the earthy Frank Lloyd Wright (who designed the Smith House in Bloomfield Hills for friends of Denison’s grandparents) to the ethereal Mies, and he didn’t feel the need to choose among them. That’s why he doesn’t have a signature style. His tastes are varied, and so — luckily for him — are his clients’.

A property in Chicago’s Bucktown includes an outdoor living room that centers on a dramatic fireplace. Photo by Dirk Denison Architects

A successful architect, he might be even more successful if he had a signature style — like, say, Richard Meier, whose white-on-white sculptures riffing on the forms of Le Corbusier are immediately identifiable.

“I’m conscious of the fact that, when you’re establishing yourself as an architect, consistency sells,” Denison relates in the book. “But to me, getting each building right is more important.”

He continues: “Listening to clients, and learning what their lives are about, is the heart of my practice. . . . The challenge of designing houses successfully is that they’re never prototypical, never generic. They’re individual.”

Our discussion begins with Denison talking about the houses he grew up in — first a Foursquare brick house in Birmingham, Michigan, and then a larger structure on a nearby lake. “It was a Southern Georgian Colonial,” Denison tells me, “a big house from the 1920s, with red tile floors, stucco walls with pecan-wood detailing, and heavy carved handrails on the stairway. It was the site that decided it — it had a beautiful rear yard that sloped down to the only lake in Birmingham. And it was in walking distance of downtown, which was important to my mother. I think at heart my mother preferred modern houses. But the benefit of a traditional house was that there were lots of walls for art.”

Recently — after our book was finished — Denison got a call from a couple who wanted him to design a house in Birmingham. (Their contractor, who knew Denison’s work, had recommended him.) When the pair drove him to the site, Denison could hardly believe it: They had purchased his childhood home and were about to tear it down.

Did Denison protest? Not at all. In fact, he says, “I’m excited about the opportunity. The property is beautiful, but the old house has no real relationship to nature. It’s from an era when a house was supposed to protect you from the landscape rather than connect you to it.”

The old house was right for Denison’s family 50 years ago. He has photographs and memories. But the new one, as I learned from getting to know Denison’s architecture, will be right for the new owners.

Purchase This Book

Or Support Your Local Bookstore