March 8, 2020In 2014, former Missouri governor Jay Nixon declared that the Henry Blosser House, a family homestead built between 1874 and 1878 by one of the Midwest’s most successful businessmen, was the most endangered residence in the state. “Almost every architectural element — fireplaces, moldings, doors, newel posts — had been stolen, stripped and discarded or vandalized,” recalls designer Kelee Katillac. “There was red graffiti in the kitchen, mold everywhere and no electricity, plumbing, water or septic. It was going to be demolished to plant another acre of soybeans.”

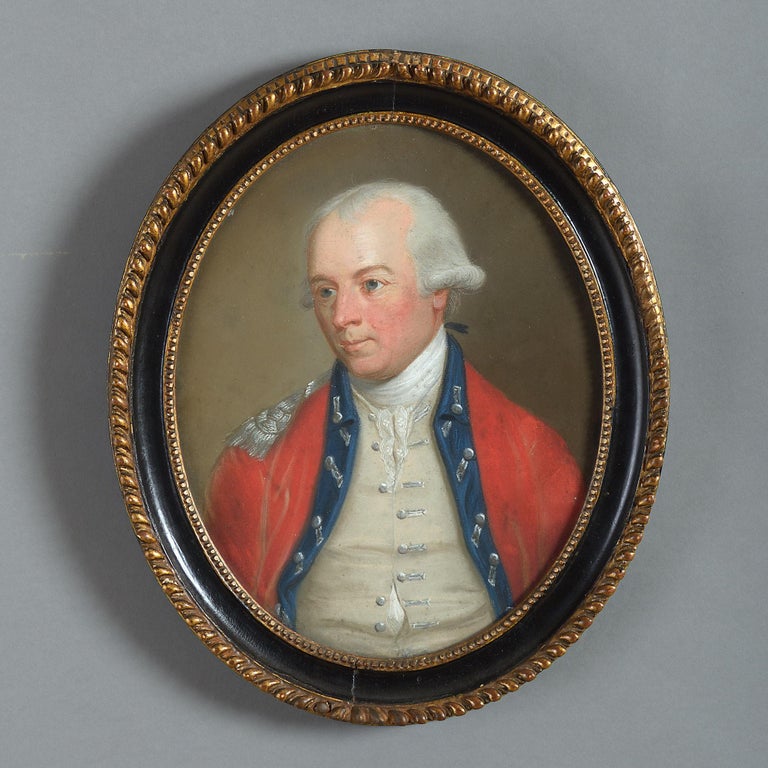

In the dining room foyer, Katillac alludes to the Blossers with gingham — very typical of Swiss country life — and horse gear and portraits. The American journey from colony to democracy is personified, so to speak, in a rare set of original-edition engravings of the republic’s first 25 presidents matted with orange silk. Top: Katillac evoked the French Empire with wainscoting composed of French coffer wallpaper medallions mounted on linen and framed in walnut. Against the wall is a Milo Baughman sofa topped with custom pillows bearing Swiss canton stamps. A portrait of a Swiss general presides next to portieres of Schumacher velvet.

Fortunately, Katillac’s clients, Dr. Arthur and Carolyn Elman, came to the rescue. The very year Governor Nixon made his pronouncement, Dr. Elman, a retired oncologist who was French consul to the Midwest, and his wife, retired director of the American Women’s Business Association, founded by her father, assumed ownership of the property from farmers who had purchased it from the last Blosser heir. Ardent preservationists and collectors of historic homes, the couple saw this as a legacy project for their home state of Missouri. To take advantage of historical tax credits, they had to restore the house as a sustainable community enterprise. Their solution: reimagine it as a decorative arts museum and its various farm buildings as a conference center and events spaces. (The Elmans can, and do, stay at the house, but federal tax-credit stipulations limit how often.)

Next to the marble Regency-style mantel in the gentleman’s drawing room is a bust of George Washington made from the maquette sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon used for one of his likenesses of the president, now in the Virginia State Capitol, in Richmond. The Regency chairs are upholstered in Federalist-blue leather.

“We also wanted to make sure that if, at some point in the future, someone purchased it as a private home or country inn, it would be turnkey,” says Katillac, a distinguished Kansas City designer and art historian. “So, we embedded all the commercial and National Park Service standards into the renovation.”

The Henry Blosser House was designed in the 1870s by Swiss-born John Daniel Walters, who blended Second Empire style with shingles in a polychrome palette typical of Alpine chalets. Designer Kelee Katillac and Steve Heiffus, her architectural partner and husband, were charged with restoring the grand residence.

The Victorian-era house was an eccentric hybrid of Second Empire and Swiss vernacular. It was the work of John Daniel Walters, who emigrated to Berne, Kansas, from Bern, Switzerland, in 1860 and established the school of architecture at the state university there. Second Empire–influenced architecture and design had long passed their prime in Europe but were a novelty in the United States. When Henry Blosser retained Walters to design the residence, the architect combined Empire details like the mansard roof with alpine chalet colors and, on the barn, Swiss-style clipped gables. In addition to executing a meticulous restoration of existing features, architect Pat Dolan and Katillac’s architectural partner (and husband), Steve Heiffus, cleaned up the aesthetic — for example, replacing the mansard’s original polychrome shingles with ones of a uniform gray.

“The challenge was to create a narrative that connected the Blossers and my clients,” explains Katillac. “I also wanted to interpret the semiotics of national and cultural design, overlaying it with the American dream. Style can be a language that translates political power. I wanted the house to tell the story of America from empire to democracy.”

For the generously proportioned dining room, Katillac drew inspiration from Thomas Jefferson’s dining room at Monticello, which is yellow. The color scheme is based as well on the typical Swiss red, blue and yellow palette, which she updated by making the blues more turquoise and the reds more orangey. This is carried through in the custom floral trims on the curtains and wallpaper borders.

Katillac and her assistant, Sherry Mirador, dove into historical records relating to the Blossers, their property and the period. “We had evidence from underlayers we discovered in the renovation that there was a lot of color,” she says. “The house had been covered in papers with a very vibrant palette. That freed me up to use color as the thread between the Blossers and the Elmans, who love color. My goal was to plug their preferred palette into the historical narrative.”

Walpole Damask wallpaper — so named because it graced Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill House, in Twickenham, West London — envelops the gentleman’s bedroom. On the wall are hung a bas relief of Abraham Lincoln (under the canopy) and various objects and materials alluding to Blosser farm life, such as equestrian accoutrements. By a window dressed in curtains suggesting the military striping of Union Army uniforms is a chair with Napoleon III–style diamond tufting and a Federalist tripod table.

From the archives at Adelphi Paper Hangings, in Sharon Springs, New York — the only commercial production facility in America that specializes in block-printed historical papers for museums — she selected 12 patterns, had them recolored and deployed them throughout the rooms. These she grounded with new gray-painted or stained blue-ash floors. Heiffus took still-existing original interior features, such as doors, and reproduced them throughout. Other architectural details were re-created from archival photographs and drawings of Blosser House.

Katillac with Silverbridge, the Blosser barn mascot. The designer worked with her clients, Dr. Arthur and Carolyn Elman, to save the derelict 1870s Henry Blosser House from destruction and restore it in a way that honors its history while adapting it for coming generations to enjoy.

“The goal was to make it relevant for now,” Katillac explains. “It’s really chic Victorian, which sounds like an oxymoron because Victorian homes were layered in a very bourgeois explosion of overwrought gilding and draping.” Drawing heavily from 1stdibs resources, she tempered that over-opulence by free-associating among a panoply of genres: from Louis XVI and Directoire through First Empire and American Federalist right up to mid-century modern.

In doing so, she created surprising synergies. For instance, the ladies’ drawing room, splashed with Carolyn Elman’s favorite pale blue, has such ornate trappings as gilded valances, Wedgwood tiebacks and embroidered star trim. Katillac describes the look as “a Federal analog of Empire,” but notes that, in a larger sense, the space represents “Empress Eugénie meets Carolyn Elman.” Her client is passionate about women’s issues, particularly those involving education, and a style maker interested in fashion and decor. So, the room is also a paean to powerful women: The mantel clock displays a plaque commemorating an American businesswoman of 1880, and scattered around are portraits of Gertrude Stein and a great-granddaughter of Sally Hemmings. “I reorganized these meanings so they have resonance for today,” says Katillac. “And this complicated history of America is woven throughout the house.”

Get the Look

Shop Kelee Katillac’s Picks