September 24, 2023Although Alvar Aalto has long been acclaimed as a master of modern architecture, it’s increasingly clear that credit for his early achievements must be shared by his first wife, Aino. The two collaborated on all the Aalto architecture studio’s early buildings and projects. Among the latter was Artek, the company they founded with two partners in 1935 as an industrial art salon in Helsinki and a means of distributing their sinuous glassware and bentwood furniture around the world.

Yet beyond their professional achievements, what was the Aaltos’ marriage like? Aino + Alvar Aalto: A Life Together, published by PHAIDON, which is celebrating its 100th anniversary, tells that story, using previously unpublished drawings, snapshots and correspondence among Alvar and Aino and their friends. The text, by Heikki Aalto-Alanen, the couple’s grandson, has been adapted from the 2021 Finnish edition, titled Rakastan sinussa ihmista, or “I love the human in you.”

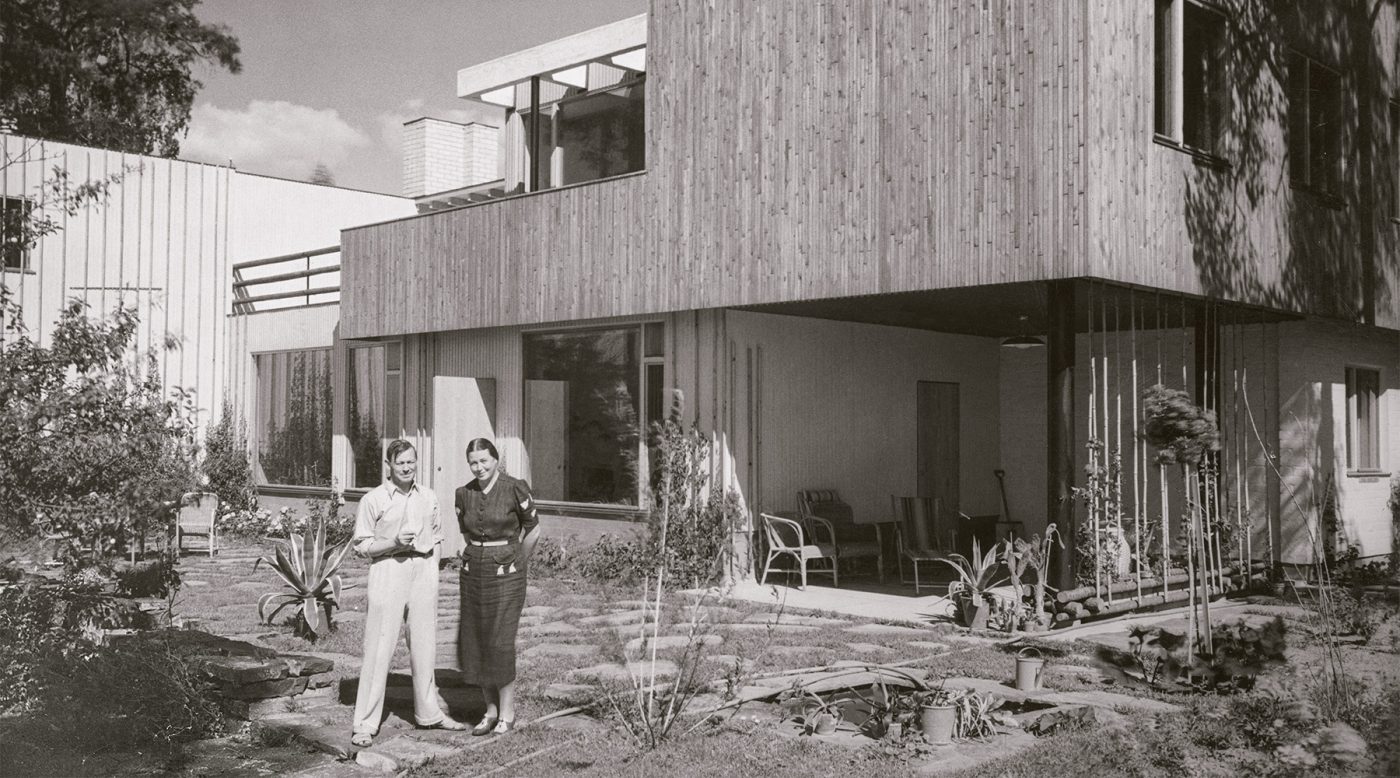

The pair met just out of architecture school, when the gregarious, impulsive Alvar hired the studious, budget-conscious Aino, one of only a handful of women to graduate from Helsinki University’s architecture program that year, as a senior architect in his first studio. They were not an obvious match: He had an “unflinching belief in his own greatness,” Aalto-Alanen writes, while she routinely described him as a “scoundrel.” Nevertheless, six months later, they were honeymooning in Venice and sketching its buildings in a shared notebook, their lives and goals newly aligned.

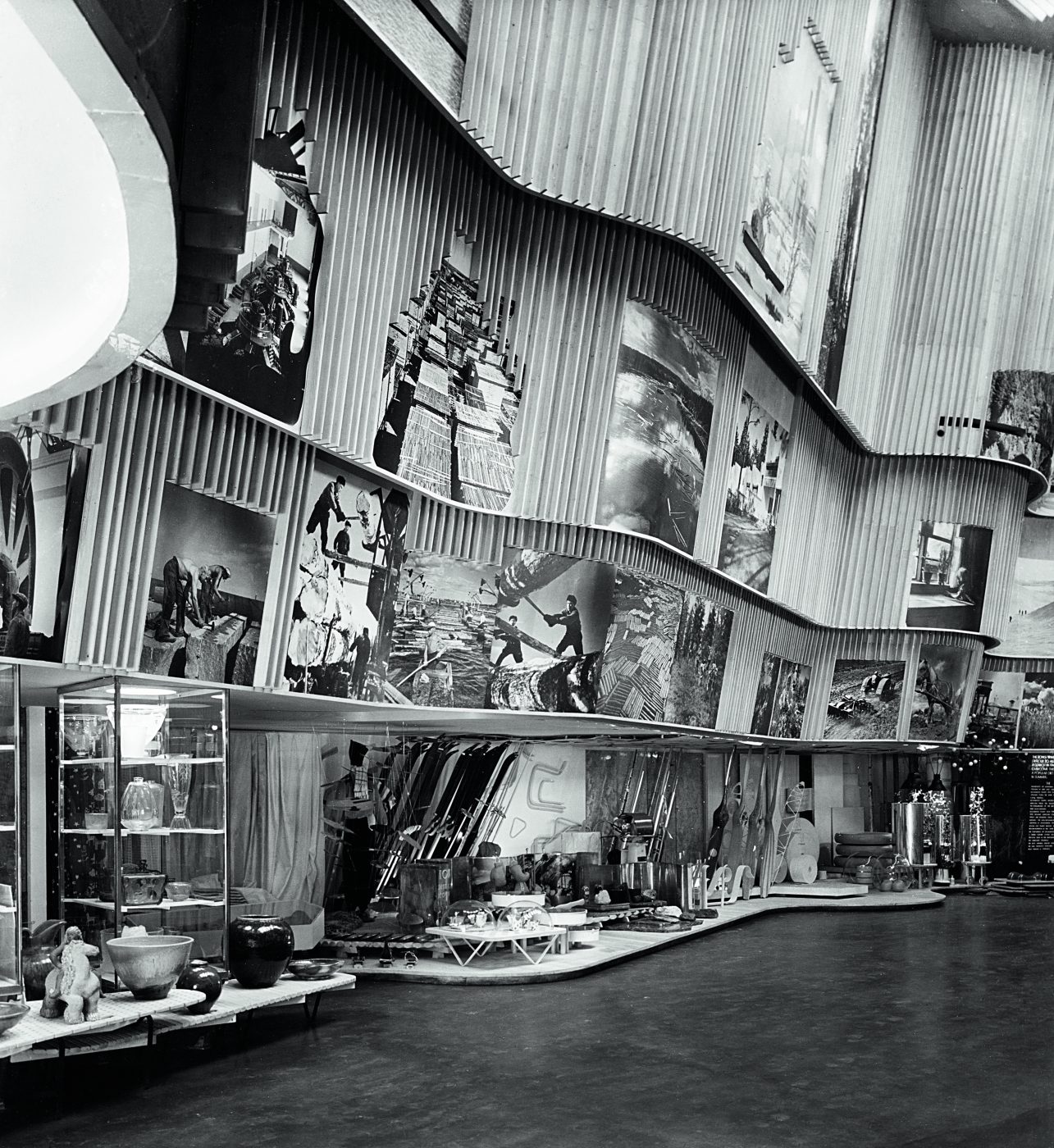

In the late 1920s, while raising their two children — a daughter nicknamed Mossi (the author’s mother) and a son dubbed Heikki, both represented here by several lovely drawings and photographs — the couple began building their modernist reputation with architectural commissions like the Paimio tuberculosis sanatorium (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) and what’s today called the Central City Alvar Aalto Library, in the formerly Finnish town Viipuri (now Vyborg, in Russia). Completed in 1935, the latter introduced the sunken reading rooms, barrel skylights and liberal use of wood that would recur throughout the couple’s work and was fully furnished by the newly established Artek with bentwood chairs and stools. The Aaltos’ booth at the 1936 Milan Triennial, painstakingly designed by Aino and again outfitted with Artek’s furniture and her glassware, much of which has remained in continuous production, took the grand prize.

As the couple traveled around the world to conferences and shows, they met modernists who would become lifelong friends, including Walter Gropius, Alexander Calder and Fernand Léger. Some of the book’s most fascinating pages involve these relationships, especially the one with László Moholy-Nagy, whom they first encountered with Gropius in Berlin, vacationed with in Finland and visited in America after the war forced him and others to flee.

Aino and Moholy-Nagy shared a love of photography and were especially fond of each other — or perhaps more than that. There’s some suggestion that the Aaltos experimented with an open marriage. On one solo trip to an architectural conference, Alvar met up with the Bauhausler and shared a nude photo of Aino. “Moholy is enthralled with your naktbild [naked picture],” Alvar wrote to his wife and “the urchins,” as they called the kids. He then exulted over his budding friendship with Le Corbusier and other architects at the conference.

Aino, struggling over the books — they had severe financial troubles early on — and clearly infuriated that she couldn’t be on the trip herself, told him to stop spending money and come home. “Send details of your return by telegram once you are on the way,” she wrote. “I cannot bear yet another disappointment.” Upon taking her own solo work trip to Oslo, during which the couple corresponded regularly, she patched it up with Alvar, telling him, “We have each other, our work and our healthy children, this is so much that one could scarcely wish for more.”

After visiting America, where their Finnish pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair was a hit, they accepted that they had to spend time apart for work. Alvar, now a starchitect, took a postwar guest professorship at MIT, while Aino remained behind, carefully guiding Artek, the engine for all their ideas.

“Work hard and flirt just enough,” Alvar wrote to Mossi while visiting Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin. “You can see where Papi is now.” He and Aino had a plan to create a Taliesin of their own, but it was cut tragically short by her death, from cancer, in 1949 at the age of 54.

Yes, Alvar went on to create many more great buildings and to marry another architect in his office. But this resonant monograph makes one wonder what else he and Aino might have accomplished together had she lived into old age — and also what she might have become known for on her own.