May 23, 2016A new show at Manhattan’s Bard Graduate Center Gallery shows off some 200 works and related pieces of ephemera that the mid-century-modern Finnish designers husband-and-wife team Alvar Aalto and Aino Marsio-Aalto created for their company Artek (photo courtesy Aalto Family Collection). Top: Alvar’s Paimio chair, 1931–32 (photo © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY). All photos by Bruce White, unless otherwise noted

The exhibition “Artek and the Aaltos: Creating a Modern World,” at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery in Manhattan through September 25, is an eye-opener, especially for those who didn’t realize that there’s a lot more to the Aaltos’ story than their iconic blond bentwood chairs and amoeboid Savoy vases, the latter of which has been a wedding-gift staple for decades.

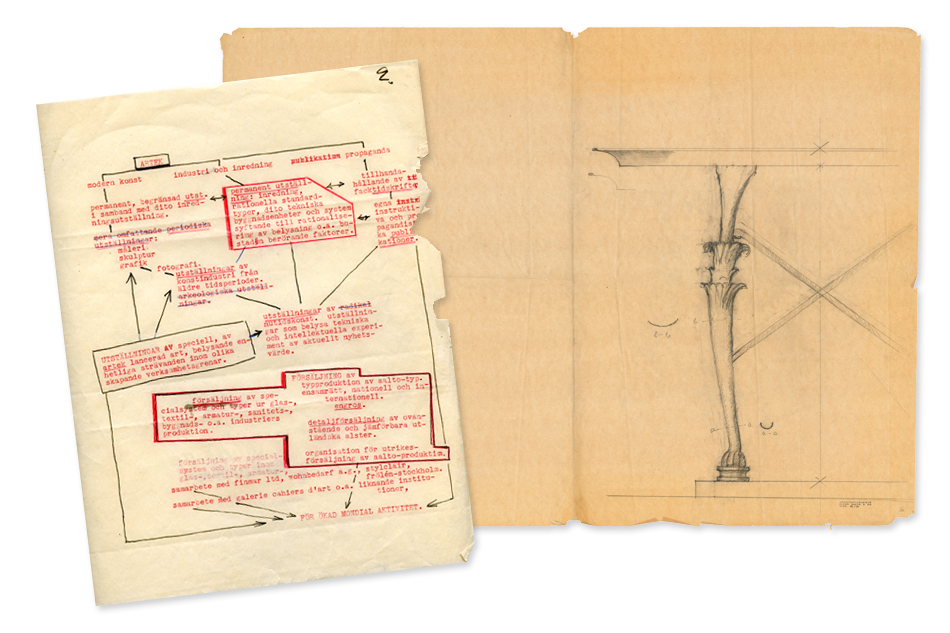

The wide-ranging exhibition, occupying three floors of the BGC’s Upper West Side townhouse, is a long-in-the-works labor of love for gallery director Nina Stritzler-Levine, who pored over the archives of Finland’s Alvar Aalto Museum and of the venerable 80-year-old furniture company Artek, which still produces Aalto-designed furniture and lighting. She also pestered members of the Aalto family to procure drawings, sketchbooks, photographs, diaries and other materials that shed new light on one of the earliest architect couples of the modern age — Alvar Aalto (1898–1976) and Aino Marsio-Aalto (1894–1949) — and the trailblazing modern-furniture company they cofounded.

“Artek was the single most popular brand of progressive furniture from 1939 through the next decade,” says Stritzler-Levine. This was the case not just in Europe but also in the United States, where Artek became a household name after the Aaltos’ work created a sensation at the 1939 World’s Fair, in New York. “It was a pioneering company that played a very important role in the culture,” Stritzler-Levine continues. “Herman Miller and Knoll are well-known and well documented. So why not Artek?”

Alvar designed this 1928 chair for the Itämeri restaurant in the Southwestern Finland Agricultural Cooperative Building, in the town of Turku.

The vast store of material Stritzler-Levine unearthed in Finland was both “a dream and a nightmare,” she says. “I was absolutely stunned by the depth of it.” Much of what’s on display at the BGC — about 200 works, many never before on public view — emphasizes the contributions of the less-celebrated Aino, who graduated in 1920 with an architecture degree from Helsinki’s Polytechnic Institute, one of the first women to do so. “She was not simply an adjunct to the practice but integral to it, ” Stritzler-Levine says.

The exhibition opens with Aino’s travel sketchbook, presented on a digital screen you can flip through, with notes and drawings made during a 1921 trip to Italy. Aino met and married Alvar, another newly minted architect, in 1924, after answering an ad he placed for help in the design office he opened in Jyväskylä, about 200 miles north of Helsinki, after finishing school.

The show proceeds more or less chronologically, tracking the couple’s extraordinary career, with photos and mementos from their visit to Germany’s Bauhaus; their trip to the International Congress of Modern Architects in Frankfurt in 1929, where they formed important friendships with Walter Gropius and László Moholy-Nagy; and the time they spent with Fernand Léger in 1937 in Helsinki, where they mounted a show of his work. One room contains examples of the bent, laminated birchwood furniture they made in the early ’30s for the Paimio Sanatorium in southwest Finland and the Municipal Library in the then-Finnish city of Viipuri (now Vyborg, Russia) — seminal pieces that would form the basis of the Artek product line for decades to come.

A crucial commission to design the interiors for a Helsinki apartment belonging to Harry and Maire Gullichsen, one of Finland’s wealthiest couples, led to the formation of Artek (an acronym derived from “art” and “technology”) in 1935. Four partners — the Aaltos, Maire Gullichsen and art historian and critic Nils-Gustav Hahl — drew up an ambitious manifesto for the fledgling company that included organizing modern-art exhibitions, designing modern interiors and promoting modernism on an international scale. “Artek was about much more than just the sale of furniture,” Stritzler-Levine says.

A 1939 photograph shows the Helsinki Artek store as it would have looked a few years after it first opened. Photo courtesy Aalto Family Collection

Artek’s flagship store-cum-gallery opened off Helsinki’s tony Esplanade in 1936. For sale inside were the wide-arm Tank chair with zebra upholstery and other Aalto-designed bentwood pieces, textiles by Aino and Dora Jung, among others, and glassware by both Aaltos and Gunnel Nyman. There were also imported Moroccan rugs and fine art. This made Artek an outlier among galleries of the era, which generally sold either design or artwork but not both. The Aaltos mixed the two, showing furnishings among Alexander Calder mobiles, Paul Gauguin woodcuts, lithographs by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and works by Léger. In the BGC show, examples of similar pieces, arrayed near a case of glassware designed by the Aaltos for the Finnish company Karhula-Iittala, convey the flavor of the chic shop, an iteration of which still exists in Helsinki today.

The late 1930s were glamorous years for the Aaltos. Artek participated in the 1936 Milan Triennale and the 1937 World’s Fair, in Paris, where the designers introduced their famous tea trolley featuring a wicker basket and big white wheel, as well as a cowhide-patterned chaise longue. In 1938, New York’s Museum of Modern Art made Aalto the subject of its first solo exhibition devoted to an architect, and the aforementioned 1939 New York World’s Fair, for which the Aaltos designed the handsome wood and copper Finnish pavilion, was a triumph that Stritzler-Levine says greatly enhanced their international exposure.

Photos from American magazines of the 1940s attest to the proliferation of Artek-furnished interiors in the U.S. Even as World War II raged, the company continued to ship furniture out of Sweden. As Bauhaus-inspired tubular steel fell out of fashion, replaced by warmer wood, “it was Aalto who came to preside over an identity for modernism for the American consumer,” Stritzler-Levine asserts. By 1948, there were 20 North American distributors of Artek products.

Alvar’s ca. 1947 prototype for a high-back stool weaves cotton webbing within the bent-birchwood slats.

As visitors ascend the curved staircase to the BGC’s upper floor galleries, the exhibition’s focus turns to Artek’s interiors projects, such as Helsinki’s Malmi Airport, completed in 1938, and to the Aaltos’ architectural commissions, represented by original sketches, floor plans and photographs. These commissions included schools, factories, residences and Helsinki’s drum-shaped Malmi Airport, designed in the late 1930s and furnished after the war. Among later projects were the undulating 1946 Baker dormitory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the couple’s most important building in the U.S., where the majority of original Aalto-made furnishings are still in use, and Harvard’s Woodberry Poetry Room, designed the following year. “What’s going on here is the creation of the artful interior,” Stritzler-Levine says.

Alvar’s final sketches of his wife (who died of breast cancer in 1949) share the third floor with a dazzling display of Aalto-designed lighting and rare furniture pieces, from a private collector in Finland, that show the variety of colors and materials with which Artek’s “standard” designs were customized.

The story of Artek and the Aaltos is far from finished — and not just because the brand lives on. Although the BGC exhibition is the most comprehensive to date, says Stritzler-Levine, “hopefully, it’s just the beginning of even more research.”