April 28, 2024The entrance to “Crafting Modernity: Design in Latin America, 1940–1980,” a sprawling exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art through September 22, features a nine-and-a-half-inch-high ebonized-wood coffee table by the architect Oscar Niemeyer (1907–2012) and a colorful site plan in gouache by the landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx (1909–1994). Both Brazilian designers were superstars; together, their work has been exhibited at MoMA more than 40 times.

Beyond the entrance, however, is work by dozens of mid-century designers who are less famous than Burle Marx and Niemeyer but whose work is getting more and more attention from curators and collectors. To these connoisseurs, what matters isn’t just how the pieces look — many are exquisite — but what they represent. “Design,” Ana Elena Mallet, who cocurated the show with MoMA’s Amanda Forment, tells Introspective, “operates as a sensitive barometer, adept at capturing the nuanced shifts in society’s political, social and cultural landscapes. It allows us to decode broader phenomena at play.” The pieces in the exhibition help trace social and political shifts in the six countries represented — Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela — each of which underwent some degree of turmoil in the years following World War II.

Certainly, a lot of meaning is embedded in the arresting tête-à-tête loveseat carved from a single piece of Brazilian hardwood by José Zanine Caldas (1919–2001). Caldas, a native Brazilian, once ran the University of Brasília’s model-making workshop. There, he sometimes made models for Niemeyer, who was chief architect for the government building authority in Brasília from 1956 to 1961 as Brazil pursued a modern and democratizing vision.

But unlike Niemeyer’s structures, with their pure forms and smooth surfaces, Caldas’s furniture is rough, displaying the effort to domesticate massive timbers by hand. In 1964, during a military coup, Caldas lost his position in Brasília. He settled in the remote beach town of Nova Viçosa, in the state of Bahia, and began carving furniture from local woods like pequi, acajou and vinhatico, at least ostensibly abandoning the modernist project. He also became known for pieces with solid — but mass-producible — wooden frames. For his Tronco line, Caldas ingeniously employed metal patterns, or molds, that allowed him to sketch the outlines of the parts he needed directly onto rough timbers before he began to cut, according to Diego Casas, of Herança Cultural, a gallery in São Paulo. (Casas obtained some of these molds from the Caldas family and mounted them in frames, he says, as “the true artworks they are.”)

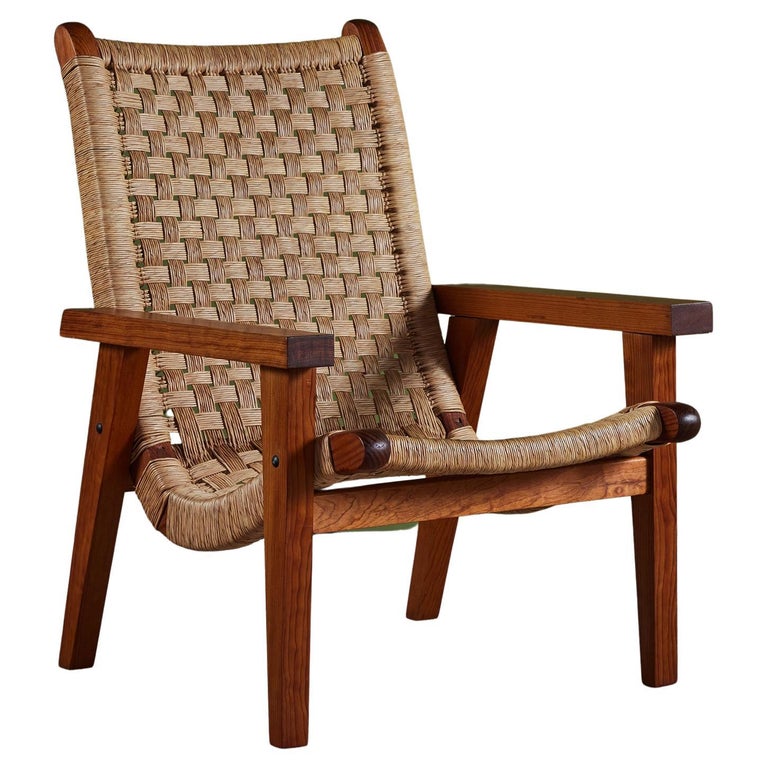

Clara Porset (1895–1981) is also having a moment at MoMA and beyond, with attention being paid not just to her designs but to her life story, with its ties to feminism, modernization and the identification of value in indigenous materials and methods. Born into a wealthy Cuban family, Porset studied at Columbia University, the Sorbonne and Black Mountain College in North Carolina, which she attended at the urging of Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and where her teachers included Josef and Anni Albers. A critic of Cuba’s right-wing government, she left her home country for Mexico, with its more simpatico regime, in 1935. With her Mexican husband, painter Xavier Guerrero, she threw herself into studying that country’s design traditions, and together the two were winners of MoMA’s Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition in 1941.

Fascinated by a Spanish-inflected Mexican wood-and-wicker chair called the butaque, she developed her own version by tweaking proportions and incorporating new materials. According to Mallet, its design was “a manifestation of her profound engagement with Mexican craft traditions” at a time when “discussions surrounding the definition of Mexican identity were paramount within the larger political landscape.” In this view, “Porset’s Butaque becomes not merely a chair but a tangible expression of the socio-political discourse of its time,” she says. Or, as Paola Antonelli, MoMA’s senior curator of architecture and design, recently told the New York Times, “This is the Latin American chair.”

Porset designed many other chairs, some in collaboration with the preeminent Mexican architect Luis Barragán. She returned to Cuba in 1959, after Fidel Castro came to power, with high hopes, but when her plans to start a design school (under Che Guevara, Castro’s minister of industries from 1961 to 1965) foundered, she returned to Mexico, where she continued to promote design for the rest of her life.

Martin Eisler (1913–1977), like a surprising number of designers in the show, was a refugee. He was born in Vienna, the son of art historian Max Eisler, one of the founding members of the Austrian Werkbund, a progressive modernist association of artists, architects, designers and engineers. Martin studied architecture in Vienna but fled in 1938, just ahead of the Nazi annexation of his country. In Buenos Aires, he became an architect, set designer and interior designer. Then, he joined forces with Carlo Hauner, an Italian designer living in Brazil with whom he eventually founded the São Paulo company Forma.

Eisler is represented in the MoMA exhibition by one of Forma’s most captivating pieces — a lounge chair from the 1950s with a curved seat that can be lifted from the base and slid into various positions. Known as Reversível, it is just one of his many adaptable designs, which also include a dining table that transforms into a coffee table.

According to Rodrigo Salem, owner of the New York gallery Found Collectibles, such pieces were tied to a specific moment in history. “In the nineteen fifties, Brazil was developing vertically,” building far more apartments than houses, he says, which meant Brazilians needed versatile furniture. So the chair, he concludes, besides being beautiful, is an artifact of Brazil’s postwar urbanization.

Gertrud Goldschmidt (1912–1994) is hardly an unknown. Nicknamed Gego, she triumphed beginning in the 1960s and ’70s with complex wire sculptures that she called “drawings without paper,” which have been the subject of important museum shows (mostly recently at New York’s Guggenheim in 2023). But much earlier, shortly after leaving her native Germany in 1939 and settling in Caracas, Gego established a workshop that made furniture and rugs, including a spectacular example in the MoMA show: the Loma Verde rug, named after a 1965 condominium building by Venezuelan architect Jimmy Alcock. Against a black backdrop, its white and brown lines are another kind of drawing without paper.

Joaquim Tenreiro (1906–1992) is yet another émigré and one whose work, like that of Caldas and Eisler, has never before been shown at MoMA. Born in Portugal to a family of woodworkers, he moved to Brazil around 1920 and became a preeminent furniture designer beginning in the early 1940s. Niemeyer himself commissioned Tenreiro to do the furniture for several of his houses.

In “Crafting Modernity,” the designer is represented by a spectacular three-legged chair made of thin layers of hardwood glued together. He alternated dark and light woods so there’s no missing how much work went into building the piece. With so many layers, “it should probably fail, but it doesn’t,” says Zesty Meyers, a principal of R & Company, which lent the chair to MoMA for the exhibition.

Tenreiro never sold one of his three-legged chairs, Meyers informs Introspective. “People have told me he would give you one if he designed your house, and that was the only way to get one. So, there are very few of these chairs out there.” And what makes the design so important, besides its unmistakable beauty? Tenreiro, Meyers says, “was showing off his skill at traditional woodworking techniques.” The shape of the chair, however, is anything but traditional — it swoops up almost like a rocket taking off. Like so many Latin American designers of that period, Meyers says, “Tenreiro was looking back at the past but at the same time taking you into the future.”