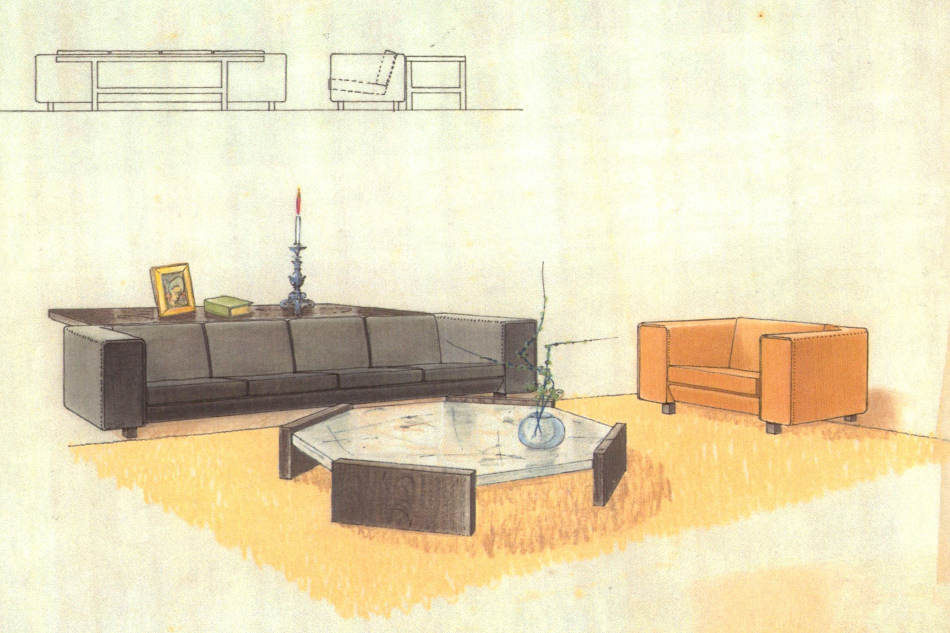

March 28, 2016Aric Chen’s Brazil Modern traces the development of modern furniture design in Brazil and offers profiles of many of its practitioners, including Sérgio Rodrigues, whose Mesa Parker dining set in solid pine, 1978, is shown above (photo by Joe Kramm / R & Company). Top: Rodrigues’s illustrated history of Brazilian chair designs for R & Company, 2011, appears in the book’s endpapers (photo courtesy of R & Company Archives)

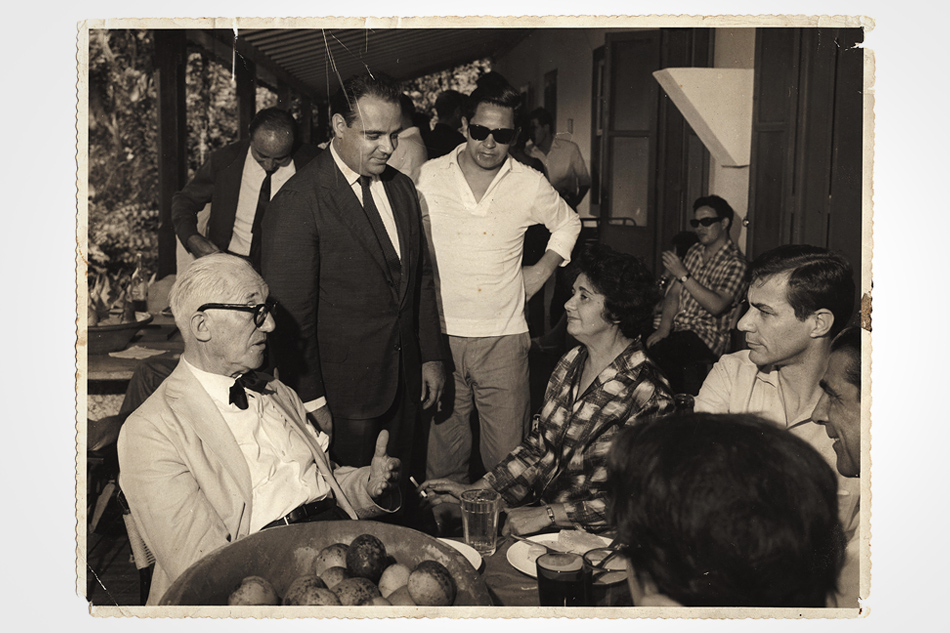

The world of 20th-century Brazilian design has long represented challenging terrain for collectors. While the sensual forms and beautifully handcrafted chairs, tables and cabinets built from exotic hardwoods by such talents as Joaquim Tenreiro, Sérgio Rodrigues and Jorge Zalszupin hold obvious appeal, the near absence of written information on these designers, let alone their lesser-known peers, has made it difficult to understand and authenticate their work.

Meanwhile, prices have been unpredictable. Many examples of Brazilian design bring just a few thousand dollars at auction, while a handful of remarkable pieces — especially those by Tenreiro, widely regarded as the father of Brazilian modern furniture — have fetched significantly more. Sotheby’s sold a Tenreiro three-legged chair for $92,500 in 2008, and Christie’s unloaded one of the designer’s low tables for about $109,000 in 2014. Compare that with the market for Italian design, where significant pieces by the movement’s leaders, including Carlo Mollino and Giò Ponti, reliably go for more than $100,000 and have even broken the $3 million mark.

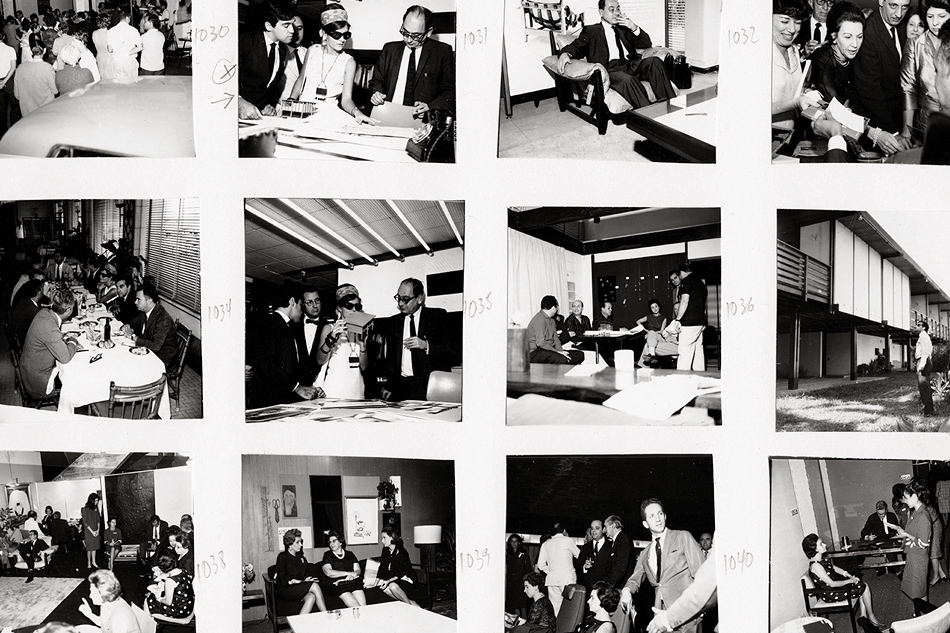

Providing some much-needed historical background is Brazil Modern: The Rediscovery of Twentieth-Century Brazilian Furniture (Monacelli Press, $60), a new photo-rich book written by Aric Chen, curator of design and architecture at Hong Kong’s M+ museum, with an introduction by Zesty Meyers, co-owner of the New York gallery R & Company. Seven years in the making, the comprehensive volume both chronicles the development of modern furniture design in Brazil and offers 15 brief profiles of its most-revered practitioners. R & Company commissioned the project after spending the past decade researching, collecting, photographing, and promoting Brazilian design.

Joaquim Tenreiro‘s three-legged chair, ca. 1947, is made of four different types of Brazilian hardwood and features solid turned joints and legs. Photo by Sherry Griffin / R & Company

“When I first started hearing about twentieth-century Brazilian design, about ten years ago, it seemed like the world’s best-kept secret,” says Chen. “There was so much amazing material, but so little was known about it.” Meyers concurs. “As far as we can tell,” he says, “this is the last great discovery of mid-century furniture in the world.”

In the text, Chen and Meyers cite a number of reasons for the relative lack of appreciation for Brazilian design until now. A source of fascination for American and European architects, politicians and curators in the early 1940s, Brazil was featured in an exhibition of Latin American architecture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1943 that went on to tour 48 cities in North America. But the country suffered a dramatic reversal of fortune when a military dictatorship took over in 1964, remaining in power until 1985.

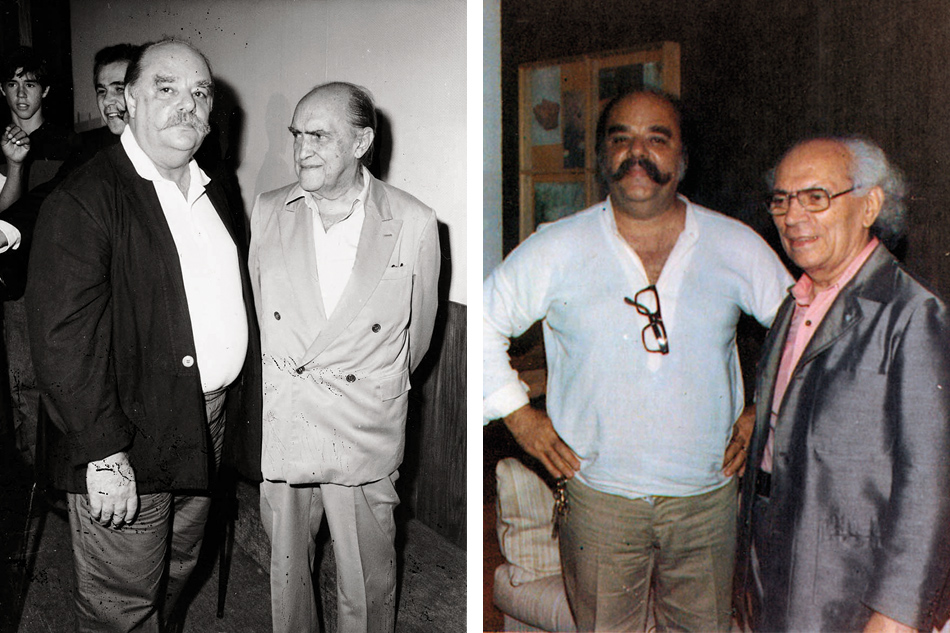

During that time, some of Brazil’s most notable designers, including architect Oscar Niemeyer, were forced to leave the country because of their communist leanings, and exports were curtailed. “The world didn’t have much of a chance to be exposed to what was happening in Brazilian design,” says Chen, noting that this relative isolation occurred “when the histories of modernism were being written.” Instead, these histories focused on designers from Europe and the United States.

In addition, says Meyers, Brazilian magazines of the period that dabbled in design had low-quality and limited print runs; most of them have since disappeared. And when some designers tried to push into the U.S. market, they were plagued by business and technical difficulties. “Zalszupin had a great story about trying to ship his work for a show in New York,” Chen says. “When it got there, all the wood was completely warped because of the difference in humidity.”

“As far as we can tell, this is the last great discovery of mid-century furniture in the world.”

The book presents a bevy of intriguing furniture to discover. Because Brazil lagged behind the developed world in industrial capacity and items were often made to order for wealthy clients, many mid-century pieces are either unique or the result of limited production runs and demonstrate remarkable workmanship.

“In the most Brazilian of designs, like those of Sérgio Rodrigues, you sense a much more laid-back attitude” than in European and American furniture, Chen says. “There’s also an emphasis on indigenous materials and ways of sitting. You see the influence of things like the hammock and woven materials and leather.” Later pieces, such as those created by Ricardo Fasanello and Niemeyer in the ’70s, used new manufacturing methods and materials like fiberglass, resin and steel to realize similarly curvaceous forms.

For Meyers, the new book is merely a jumping-off point for deeper exploration. “We published this book first so we could start to do individual monographs next,” he says, noting that Tenreiro and Rodrigues are first up. “We’re still just at the beginning.”

Or Support Your Local Bookstore