August 22, 2012While working at Herman Miller, Alexander Girard (top) created a series of silk-screened cotton “Environmental Enrichment” panels decorated with his signature bright colors and graphic motifs, including this one, entitled Bouquet, 1972, and available from Bright Lyons. All images © 2011 Todd Oldham Studio/courtesy of www.ammobooks.com

By and large, the early makers of modernist design, art and architecture presented a rather humorless face to the public. Photographs of Bauhaus eminences such as Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe generally show them as sour, superior members of the Mitteleuropa intelligentsia. Architects like Austria’s Adolf Loos produced such stern essays as “Ornament and Crime,” and French designers from the 1930s through the ’50s debated design ideas as if they were disputing national politics.

Yet there was a large contingent of mirthful moderns. The artist Alexander Calder created his famed “Cirque Calder,” a colorful cavalcade of miniature acrobats and lion tamers made of wire. Charles and Ray Eames decorated their home in suburban Los Angeles with an endearing group of ethnographic dolls and puppets, and they even hung a tumbleweed from their ceiling as an objet d’art. But for joy and brio, likely no one could top Alexander Girard, the director of design for the textiles department at Herman Miller, Inc., from 1952 to 1973. He introduced bright, bouncy colors to upholstery and drapery fabrics, created jaunty graphics for marketing and advertising materials and devised motifs for everything from textiles to ceramics based on his true love: folk art from cultures around the globe.

Todd Oldham and Kiera Coffee’s tome weighs in at 672 pages and around 14 pounds.

“Girard had incredible vision and taste,” says Paul Bright, co-principal of the Brooklyn gallery Bright-Lyons. “He dug deeply into folk art traditions because he appreciated their honesty, playfulness and naïve qualities. They were the greatest influence on his work.”

Though he died in 1993, Girard has lately been winning new admirers. In June, Herman Miller reissued five textile designs from the Girard archives. (Bright contributed a number of vintage Girard pieces for a long-term exhibition at the firm’s showroom at Chicago’s Merchandise Mart.) And a few months ago, the fashion designer Todd Oldham and design historian Kiera Coffee published Alexander Girard, a lavishly illustrated and deeply researched review of the designer’s career (Ammo Books). The book runs to a staggering 672 pages, which is no less than its subject merits. As a person who worked not only in textile and graphic design, but also on typography, furniture, ceramics, tableware, illustration, interiors, restaurant design and architecture, and who even devised a new look for a commercial airline, Girard may well have been the most prolific and protean designer of the mid-20th century.

Girard’s innovative “Environmental Enrichment” pieces include, clockwise from top left, Clover (1972), Double Heart (ca. 1970), Geometric B (ca. 1970) and Stars (1972), all of which are available from Bright Lyons.

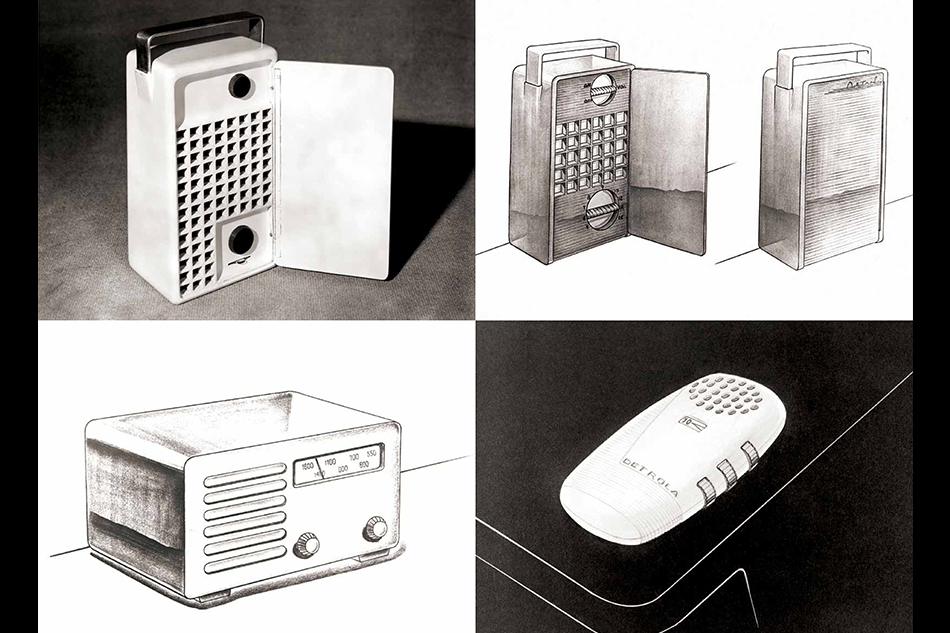

The son of an American mother and an Italian father, Girard (known as Sandro to his friends) was born in New York City in 1907 but raised in Florence. He came from a creative family — his father was a master woodworker — and Girard began drawing and making his own playthings as a youngster. He had a fascination for nativity crèche tableaux, an enthusiasm that likely was the germ for his later interest in folk art. He went on to earn degrees in architecture at schools in both Rome and London before returning to New York in the 1930s and working in interior design. By the 1940s, he and his wife, Susan, had moved to Detroit, where Girard was head of design for Detrola, a firm specializing in tabletop radios. The elegant bentwood housings that he developed for the devices won him acclaim, but, more importantly, at Detrola he met Charles Eames. The two became lifelong friends, and it was Eames who drew Girard into the Herman Miller fold.

The company had no dedicated textile department until Girard arrived, and most of its furniture was upholstered in mundane, “safe” hues. Girard changed all that, introducing fabrics in vivid shades of red, orange, yellow and blue. His early designs incorporated geometric motifs — stripes, circles, square, triangles and such. But toward the end of the 1950s he began to introduce folk art themes into his designs. As Oldham and Coffee note, Girard did not collect important or expensive folk pieces. Rather he was drawn to simple objects such as handmade toys, figurines and models of animals, buildings and plants. The fabrics that emerged had whimsical, lighthearted motifs depicting, for example, angels, children, birds and flowers. Toward the end of his term with Herman Miller, in an effort to achieve what he termed “aesthetic functionalism,” Girard produced a group of what he called “Environmental Enrichment” pieces. These were silk-screened cotton panels emblazoned with various graphic designs, from bold geometric patterns to folk art themes. They were meant to divide spaces in offices or the home in lieu of walls while simultaneously functioning as art. Today, panels of vintage Girard upholstery textiles have become premium collectibles.

“Girard had incredible vision and taste. He dug into

folk art traditions because he appreciated their

honesty, playfulness and naive qualities.”

Girard was known as much for his multifaceted creative talents as he was for his quirky, playful sense of humor, here demonstrated in a set of articulated wooden toys he created in the 1940s.

Girard returned to the same motifs again and again throughout his career, including that of a coiled snake, which appears here in decades-spanning sketches and atop a 1960s steel table.

Girard’s furniture is less well known, primarily because most of it was designed for private commissions. The market for his work in this area is “emerging,” in the parlance of the trade. As recently as 2010, Christie’s sold a circa-1964 gilt-bronze and brass coffee table by Girard and a wall clock decorated with an image of a serpent encircling itself — a favorite Girard motif. One Girard design that Herman Miller did put into production was based on work he did for Braniff Airways. In 1965, when air travel still had some cachet, Braniff decided to spruce up its look under the marketing slogan “The End of the Plain Plane.” Girard was brought in and promptly had the hulls of the company’s jets each painted in one of seven vibrant colors. He upholstered the seats in a snazzy checked fabric, and — being a designer who believed in having a hand in all aspects of a commission — redesigned every element aboard, down to the playing cards and sugar packets. (He hired Emilio Pucci, however, to design the flight attendants’ uniforms.)

For Braniff’s airport lounges, Girard designed settees and chairs with sleek curving seats and floating back rests. In 1967, Herman Miller issued the furniture with slight modifications (the settee became a three-seater sofa, for example) then dropped the line the following year. These pieces, though rare, occasionally come to market.

The project that may have best showcased Girard’s multiple talents was a restaurant: La Fonda del Sol, a pan-Latin boîte that opened in 1960 in New York’s Time & Life Building. The establishment was owned by the firm Restaurant Associates, which intended La Fonda to serve as a lively counterpoint to the more reserved modernism of another of its holdings, the Philip Johnson–designed Four Seasons restaurant. Thanks to Girard, it may have been the most exuberant eatery in town. He created, essentially, a Latino cabinet of curiosities, with staggered niches holding pre-Columbian artifacts and, of course, his beloved folk art. Signage in a perky font pointed the way, in both English and Spanish, to every area, from the restrooms to the bar. As was his wont, Girard’s design hand was far-reaching — although he did farm out the design of the chairs to Charles Eames — from the colorful waitstaff uniforms and columns in chrome that suggested palm tree trunks to the pastel tableware and cutlery. Girard crafted tiles depicting more than 40 different illustrations of the sun.

Girard may have been the most prolific and protean designer of the mid-20th century.

In connection to a show at Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center that included Girard’s work, textile designer Jack Lenor Larsen wrote in the Design Quarterly: “[T]he prime concern of environmental design was how people feel in a space. This is Girard’s message and his main contribution. At a time when modern architecture was becoming a larger, more standardized aspect of the corporate establishment, the success of La Fonda whetted our appetites for more romantic, diversified interiors.” (Ephemera from the restaurant are not difficult to find, including large serving dishes and glassware sets and such smaller items as salt-and-pepper shakers and matchstick holders.)

Girard’s most lasting contribution, however, may be his folk art collection. He and Susan had begun gathering pieces shortly after their marriage, in 1936. By the 1970s, they had amassed the world’s largest collection of cross-cultural folk art, composed of more than 100,000 pieces from around the world. The Girards donated their holdings to the Museum of International Folk Art, in Santa Fe (where they had moved in the ’60s), quintupling the institution’s collection, and a new wing — named for the Girards — had to be built to hold it. That building opened in 1982 with a 10,000-item exhibition curated by Girard and entitled “Multiple Visions: A Common Bond.” That show is still in place after 40 years, highlighting ceremonial masks, beadwork, costumes and thousands of toys and figurines. It is visually staggering, fun, funny and edifying — a work of art unto itself.

“I think Girard wanted to show that there was common ground between every culture and that there are universal themes that all peoples have tried to explore through art,” says Bright. “You have to remember the times in which Girard was working. There was the Cold War, Vietnam, social upheaval, political assassinations. I believe that he wanted to send a reassuring message: that for all our troubles, the world is still a good place.”