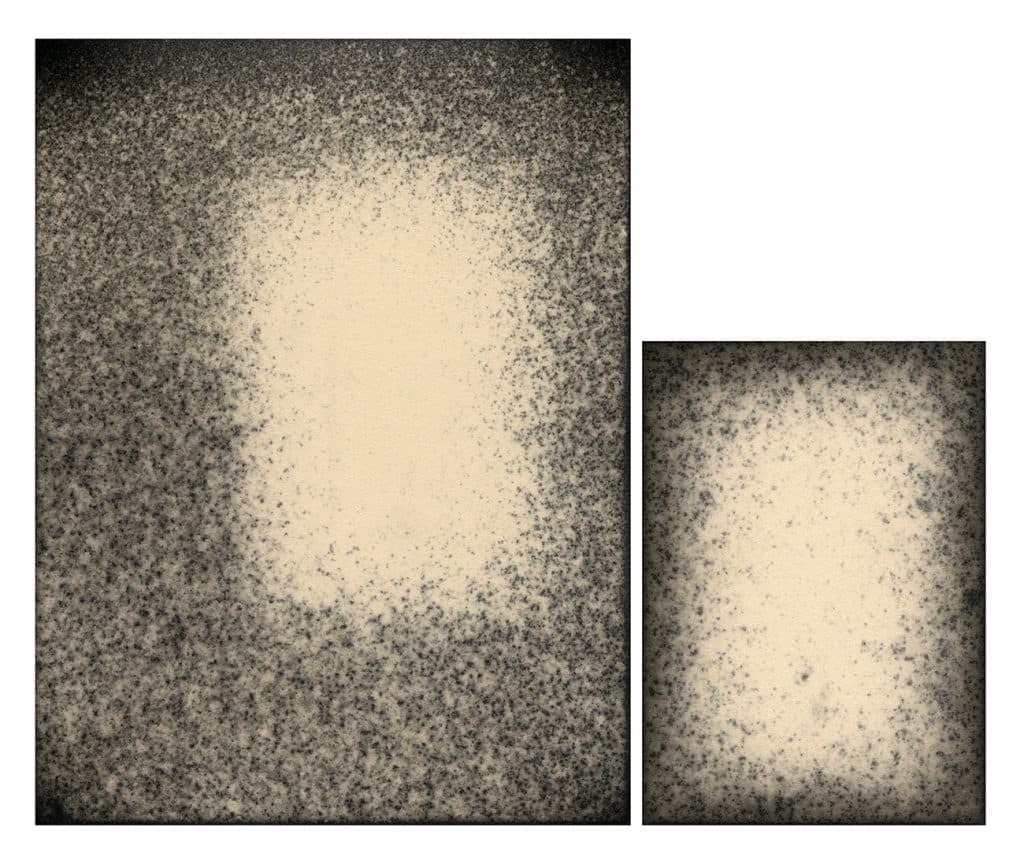

April 5, 2020Photographer Alison Rossiter applies darkroom chemicals to vintage photo paper and then often arranges the sheets into compositions, as in Density 1928, 1929 (2020). Top: A visitor at New York’s Yossi Milo Gallery considers a piece Rossiter made using Gevaert Gevaluxe Velours, a type of photo paper dating back to the 1930s that was designed to look like velvet. All photos courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery unless otherwise noted

The 21st-century rise of digital photography has had people dismantling their darkrooms and getting rid of obsolete printing materials, including light-sensitive paper. But one photographer’s trash is another’s treasure.

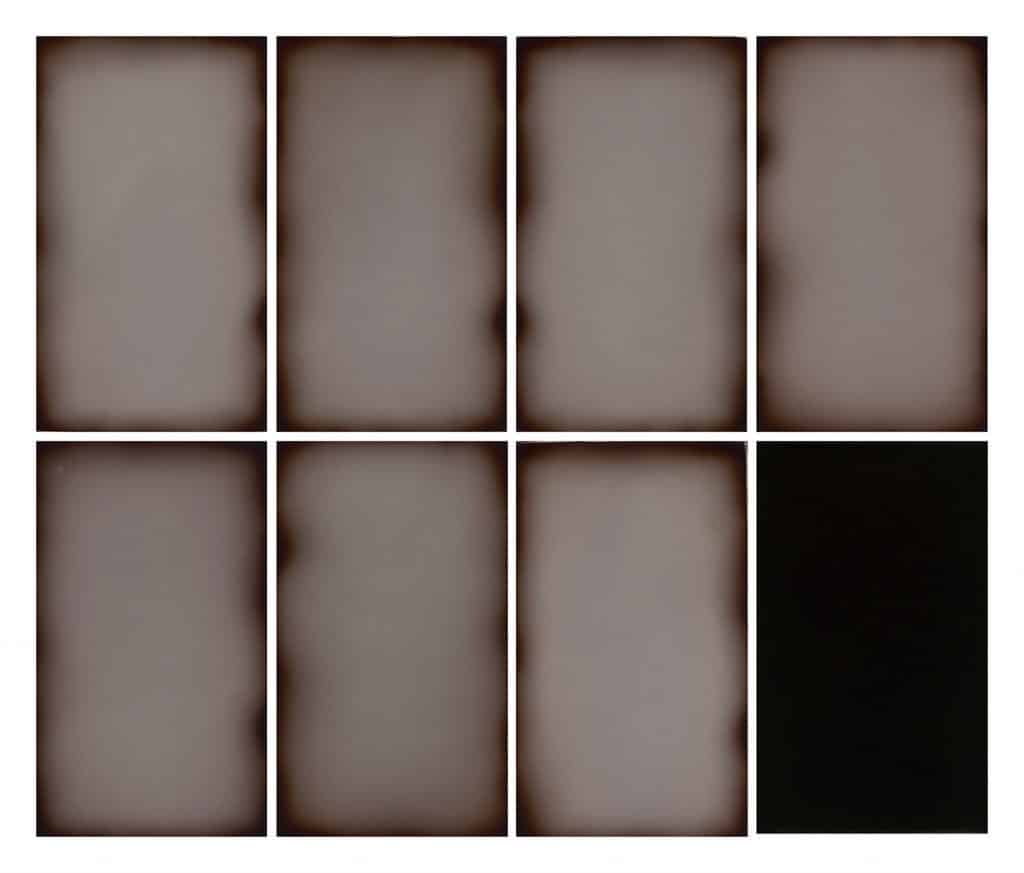

Since 2007, ALISON ROSSITER has compulsively collected packages of expired papers, predominantly on eBay, and revealed the accidental compositions wrought on them by atmospheric pollution, mold, fingerprints and stains. The results — achieved by developing light-sensitive paper in a darkroom that hasn’t been dismantled — are called photograms.

Rossiter’s Photograms Reveal Historical Elements

Some of Rossiter’s camera-less images were included in “Substance of Density 1918–1948” at Yossi Milo Gallery, in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood during 2020. Many of these astonishingly beautiful abstractions, in a nuanced range of tones from white to black, call to mind paintings by such artists as ROBERT RYMAN, AGNES MARTIN and Sean Scully.

For this show, Rossiter used papers dating to the end of World War I through World War II and on to the creation of Israel as an independent state. In her poetic conceptualization, as she sees it, something of this particular time in history has left its shadow on these papers.

The photograms in the show were accompanied by a timeline of events that happened during these years, which, Rossiter suggests, “is enough to place you in those decades, and then you can bring your own imagination.”

Alison Rossiter’s photograms depict the effects of light and other damage to photo paper over the years.

The exhibition was part of Rossiter’s project to develop sheets from some 2,000 packages of paper she’s collected, dating from the 1890s through the 20th century. Examples from the earliest two decades were displayed at, and acquired by, the NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY.

Rossiter’s monograph Compendium 1898–1919 was co-published by the gallery, the New York Public Library and Radius Books. Radius also published Expired Paper, Rossiter’s first compilation from the project, which was named one of Aperture’s 10 best photo books of 2017.

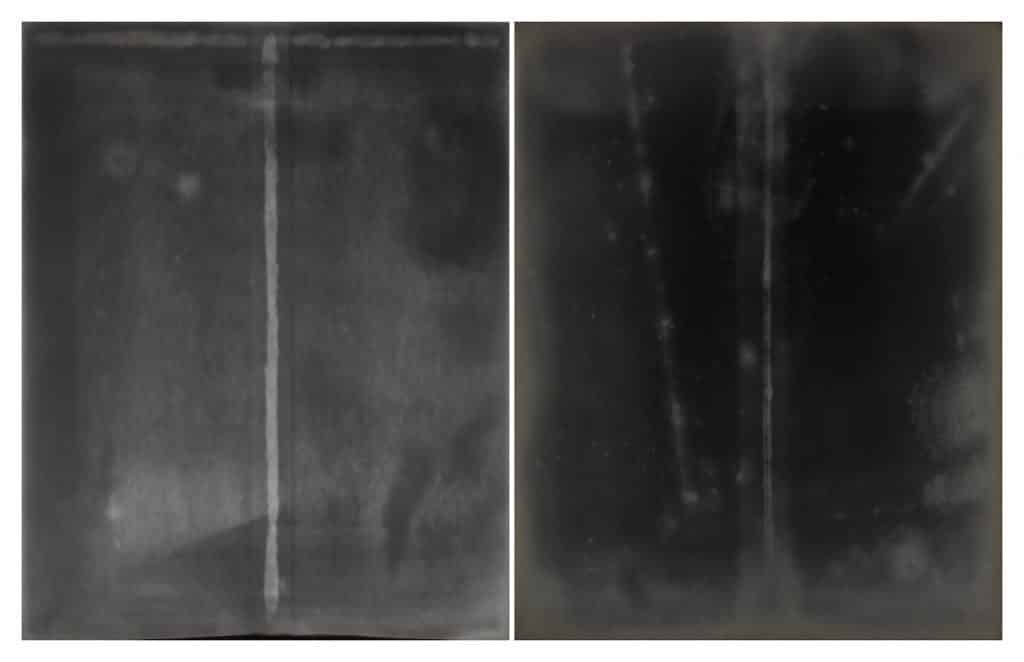

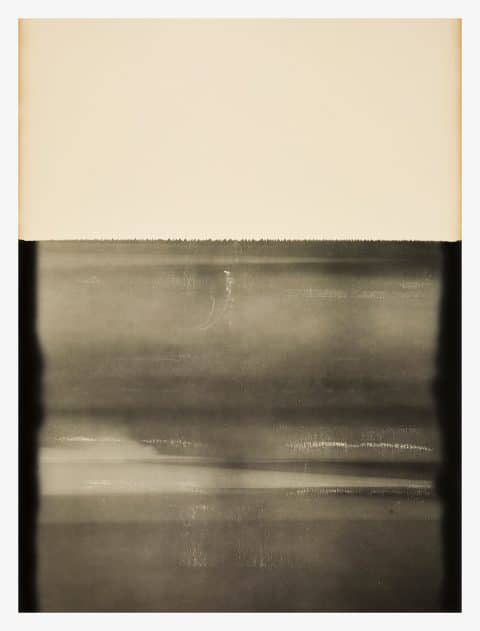

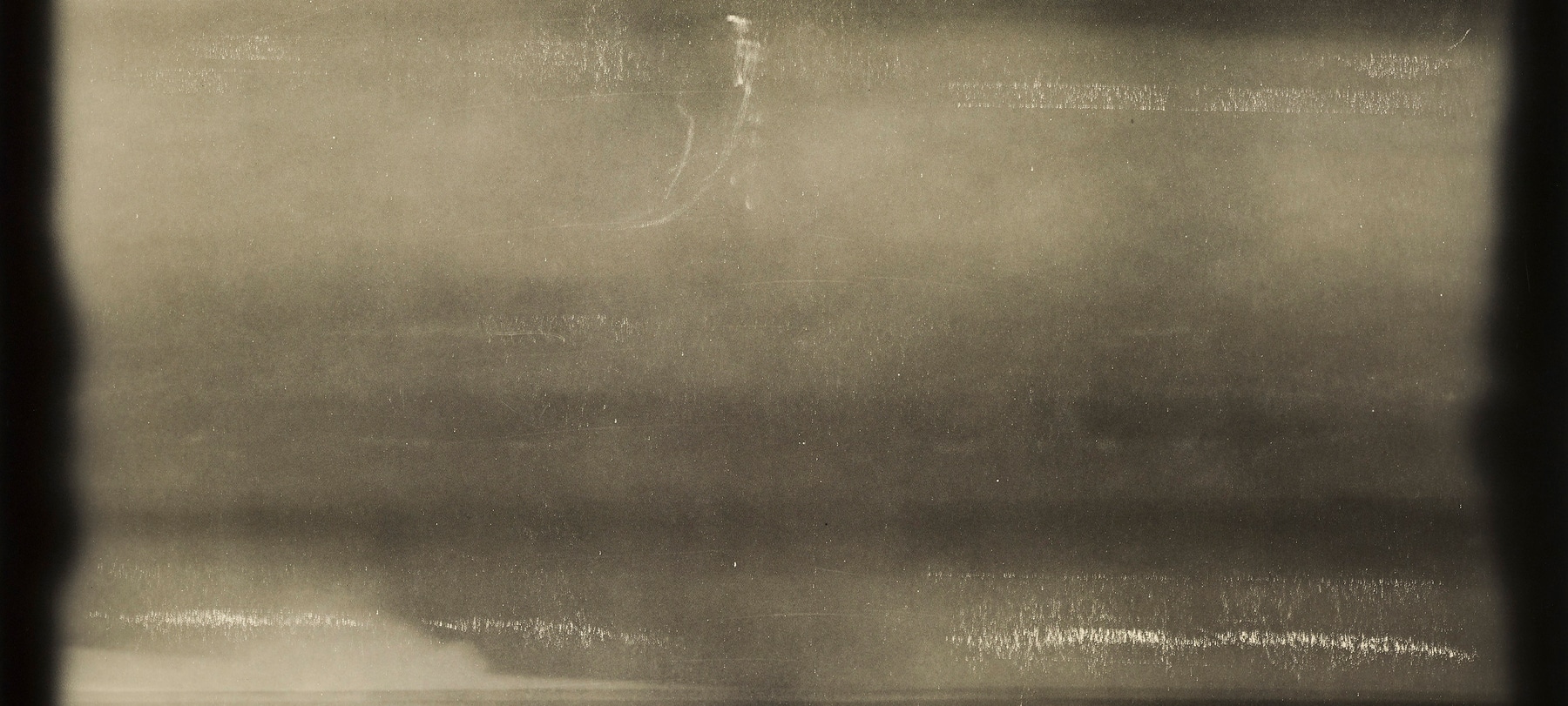

For some of the pieces Alison Rossiter made using the 1930s Gevaert Gevaluxe Velours paper — including Gevaert Gevaluxe Velours, exact expiration date unknown, ca. 1930s, processed 2020 — she dipped only the lower section in developer, creating the suggestion of a horizon line.

“Alison collects the discarded, going back into history, and celebrates the physicality of her materials,” says Yossi Milo, THE GALLERY’S EPONYMOUS FOUNDER, noting that Rossiter’s photograms are sought out by collectors of all stripes, as well as by curators from such institutions as the MUSEUM OF MODERN ART in New York; the NATIONAL GALLERY, in Washington, D.C.; and the ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO. “Each of her unique works is a record and witness of the wear and tear of time.”

Alison Rossiter’s Surprise Shipment of Expired Photo Paper

Rossiter, who was born in Mississippi in 1953 and studied photography at the ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY in New York and the Banff School of Fine Arts (now the BANFF CENTRE FOR ARTS AND CREATIVITY) in Alberta, Canada. She discovered the potential of expired papers within fine art photography by chance in the late 2000s.

Buying old film online for photograms she was making, she received a box of paper from 1946 thrown in with her shipment. As a test, she ran a sheet from the center of the stack through darkroom chemicals. “If it was a good paper, it would turn out to be a white sheet at the end, meaning there was no exposure,” Rossiter says.

Instead, because of the sheet’s deteriorating emulsion, the process produced what looked like graphite rubbed over a rough surface. It had the ethereal quality of a Vija Celmins drawing of a night sky, and for Rossiter, it was a like a bolt of lightning.

“From what I saw, my hunch was that failure of the emulsion could be happening in every single package of old paper,” says Rossiter, who had spent two years volunteering in the MET’s photography conservation department. She has since dedicated her darkroom practice to uncovering the small miracles embedded in these materials, while always leaving some paper in each package to keep it “alive,” as she puts it, for future study by conservators. “It’s a history of the industry,” she says.

A detail of Alison Rossiter’s Gevaert Gevaluxe Velours, exact expiration date unknown, shows the marks of time revealed by her process.

Taking Inspiration from Modern Art

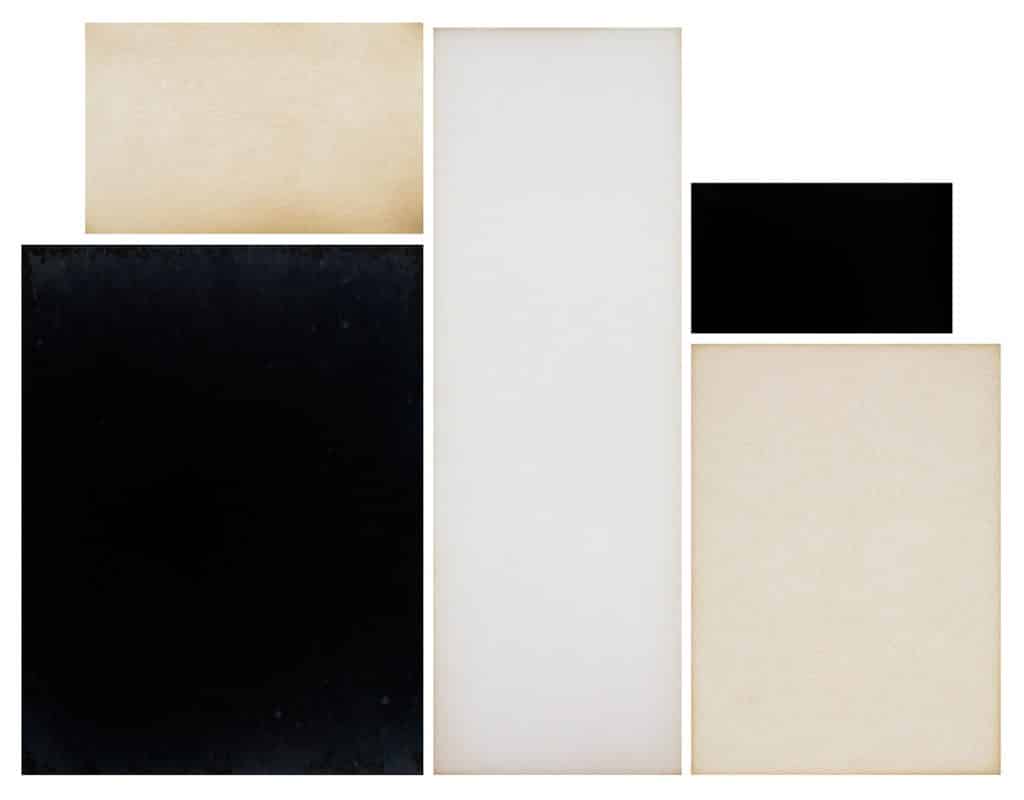

Rossiter’s photogram Density 1922 (2019) — titled, like all the works in the show, with the expiration date on the package of paper used — consists of a large off-white and a smaller black sheet positioned next to each other, the former containing a tilted rectangle of a brighter white the size of the black sheet. The work resulted from Rossiter’s observation in the darkroom that the smaller sheet, a test print that had lain at an angle for almost a century on the stack of paper, had created an image on the top sheet akin to Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918). She put the larger sheet in fixer, to maintain the whites, and developed the test print, which came out black because of the air that had seeped into the package over time.

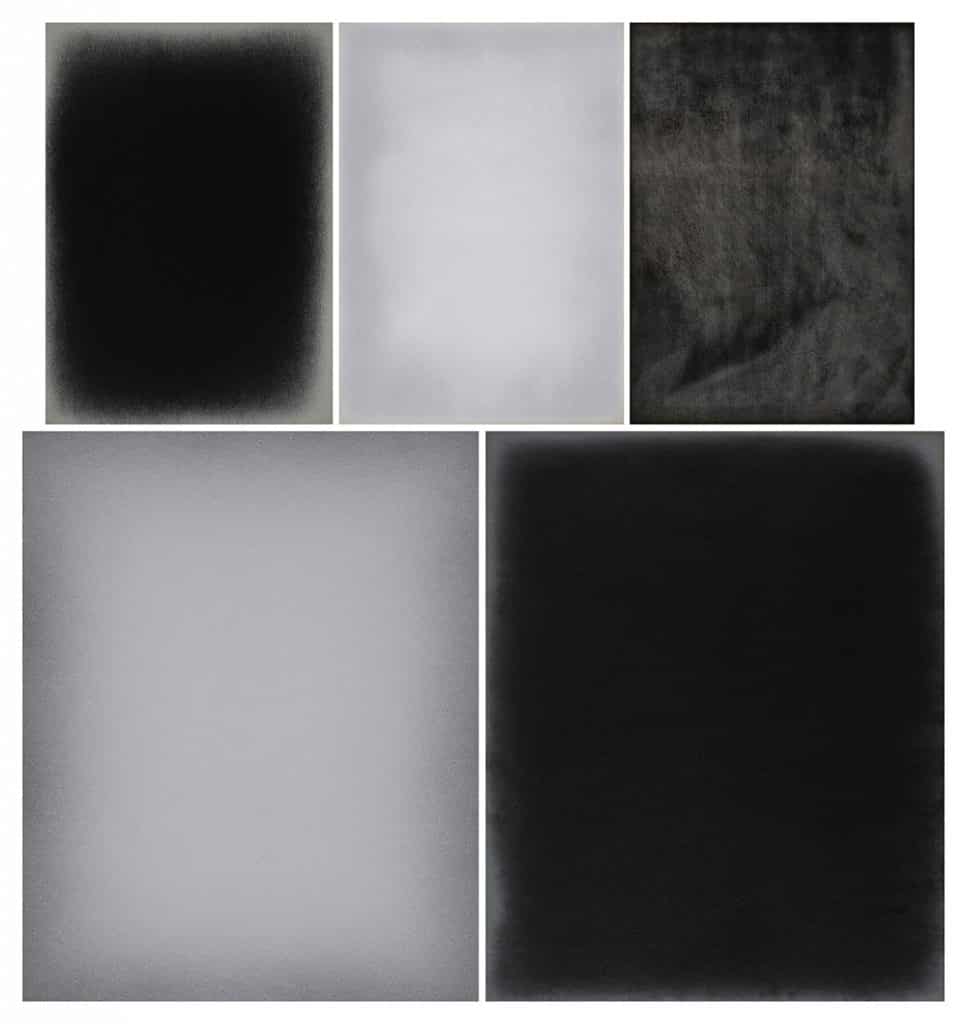

For another grouping of photograms — which used papers from 1919 to 1923, the EARLY YEARS of the Bauhaus — Rossiter assembled a geometric patchwork of five rectangles in shades of black and white. “It looks like it could have been somebody’s homework project at the Bauhaus,” she says, noting the sooty smudges on one sheet. “Somebody took the thing out of the package and put it back for some reason. I come along, and it’s like forensic fingerprinting. It’s a communion of sorts, photographer to photographer, printer to printer.”

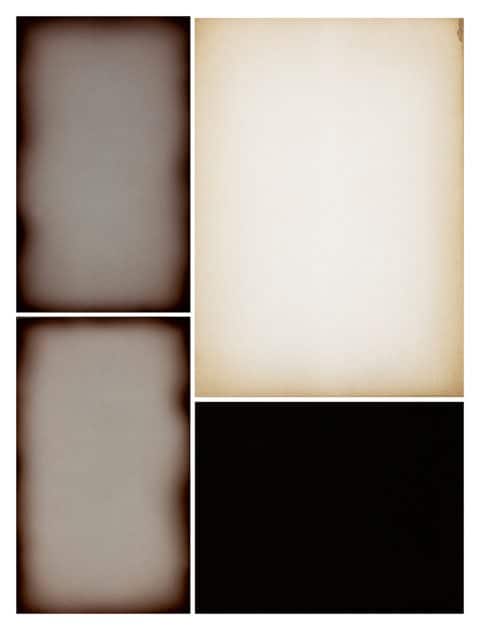

Alison Rossiter’s photogram Density 1936 (2020), like all the pieces in the show, includes in its title the expiration date on the package of photo paper used to make it.

Rossiter doesn’t typically set out to echo modern or contemporary artists, but she likes the dialogue that often occurs organically. She remembers being inspired by a show at MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY of ELLSWORTH KELLY’s small black-and-white paper works from the 1950s. “I thought, this is exactly what I’m seeing in my papers,” she says. “Ellsworth Kelly has given me permission to put my little prints together and call that a piece of art.”

Although Rossiter considers most of her works to be found images and puts the whole sheet used for each in either developer or fixer, she makes deliberate marks on some, especially when the paper is particularly special. Several pieces in the show are made from a wide roll of 1930s Gevaert Gevaluxe Velours, which was designed to look like velvet. The paper was passed down from one Belgian photographer to another, who saw Rossiter’s work and contacted her with a gift of half his roll.

Fine art photographer Alison Rossiter creates photograms from some 2,000 packages of photo paper she’s collected. Photo by Alison Rossiter

For two 68-by-53-inch works, Rossiter wet the whole sheet with water but dipped just the lower sections in developer, thus creating implied horizon lines. In each, the bare creamy paper of the upper section reads as sky while the inky washes streaking across the lower half suggest an ethereal landscape at dusk. Those streaks reveal that the paper was unfurled and briefly exposed to daylight at some point in its history.

“Because I know THE RARITY OF THE PAPER and the fact that a man in Belgium sent it to me because he liked what I was doing with papers, this is hugely thrilling,” Rossiter says of the story embedded in these pieces. “It is the most exciting thing that has ever happened in this entire project for me.”