A century ago in Weimar, Germany, architect Walter Gropius established the Staatliches Bauhaus, a novel type of design school that united art, craft and technology. Gropius’s ambition — shared by the diverse crew of architects, artists and designers who signed on to be a part of the experiment — was to shape a new, modern way of living.

The school moved in 1925 to the city of Dessau, where it enjoyed its heyday under Gropius, then Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The period from 1932 to 1933 when it operated in Berlin under Mies was its final chapter, but it was not by any means the end of its influence. Although it existed for just 14 years, the Bauhaus left a tremendous legacy whose impact is still felt today.

A yearlong celebration marking the centennial of the school’s founding is now in full swing. “100 Years of Bauhaus,” which kicked off in January with a nine-day festival in Berlin, encompasses a dizzying schedule of events throughout Germany and around the globe, including a slate of major exhibitions and the launch of new museums in each of the three main Bauhaus cities.

The Bauhaus-Museum Weimar, set to open April 6, will house the world’s oldest collection of the school’s works, combining an examination of the movement’s history with an exploration of ways its principles might be applied in the future. “Bauhaus Imaginista,” a traveling exhibition and research project tracking the global dissemination of Bauhaus ideals, culminates in a show at Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt that starts its run in March. And the Grand Tour of Modernism takes visitors around Germany to view examples of Bauhaus and modernist architecture, from the Haus am Horn, in Weimar, to a pair of Le Corbusier houses in Stuttgart that have been added to the Unesco World Heritage list.

From textiles to typefaces, furniture, objects and architecture, Bauhaus creations continue to have an outsize influence on design. Here are a few of our favorite examples.

Marianne Brandt, known mainly for her products in metal and glass, began as a student at the Bauhaus in Weimar in 1923. She became a master at the school in Dessau, directing the metal workshop from 1928 to 1929. Brandt designed this minimalist paperweight in green- and black-lacquered metal for German manufacturer Ruppelwerk.

The Bauhaus Lamp, as this piece is known, was designed in 1924 by Bauhaus student Wilhelm Wagenfeld, along with Carl J. Jucker. Among the icons of the style, it is noted for its functional simplicity and geometric structure (à la László Moholy-Nagy, Wagenfeld’s teacher). The circular base is blue Lucite, and the stem supporting the domed glass shade is chrome. In other versions, the body and base are nickel-plated steel.

One of the Bauhaus’s greatest figures, Marcel Breuer pioneered the use of tubular steel in furniture design. His B3 chair, designed in 1925, later became known as the Wassily chair, after painter and fellow Bauhausler Wassily Kandinsky. In this version, produced by Knoll and featuring brown leather straps, the timeless frame is steel with a chrome finish. Fun fact: Breuer’s inspiration for the chair, part of the collection designed to furnish the Dessau school, was the bike he rode around campus.

Although their creator is unknown, the design of this pair of cotton wall or floor rugs was influenced by Gunta Stölzl. Originally a student at the Bauhaus, Stölzl was the director of its Weaving Workshop from 1926 to 1931.

These classic tables, designed by Breuer, embody the Bauhaus principles of simplicity in function and form, balance, proportion and harmony.

Wassily Kandinsky, considered by some the father of abstract art, was appointed by Gropius to teach in Weimar in 1922 and remained with the school until its closure in Berlin in 1933. This drypoint print on wove paper is part of his “Small Worlds” portfolio. Created the same year he joined the Bauhaus, the group comprised four lithographs, four woodcuts and four drypoint works, in color and black and white.

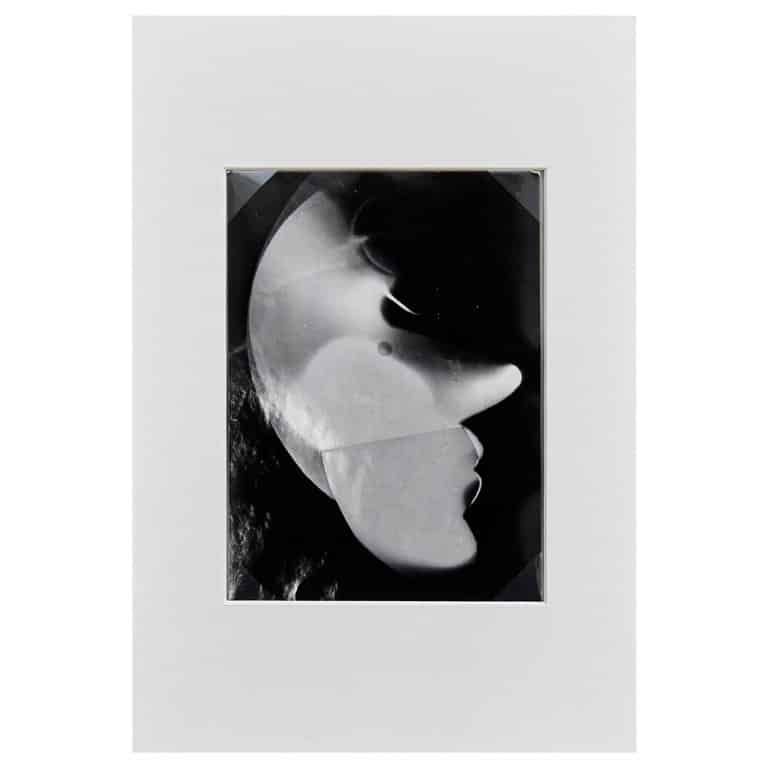

This untitled camerless photograph, or photogram, was taken by Bauhaus master Moholy-Nagy, who experimented with the format throughout his appointment at the school.

Another of the movement’s icons, the Barcelona chair was designed in 1929 by the school’s third and final director, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Bauhaus master Lilly Reich for the German Pavilion at that year’s Barcelona International Exposition. This version was produced by Knoll in the 1960s.