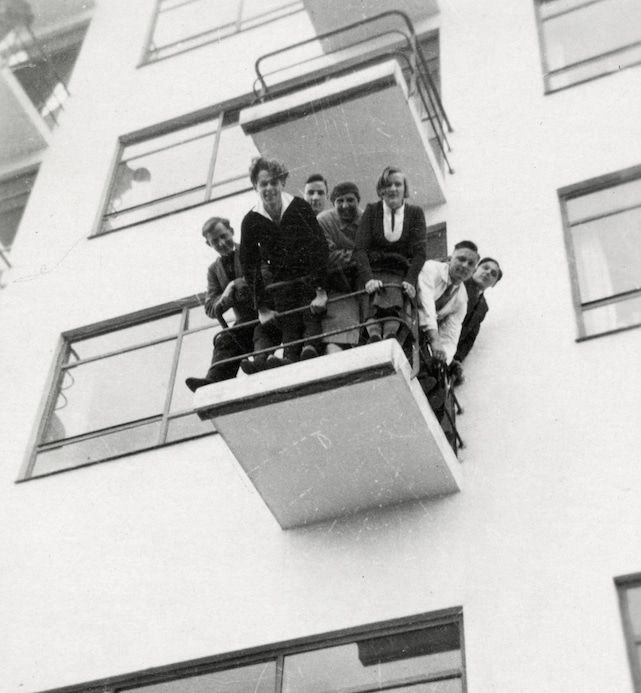

Bauhaus students on a balcony of the studio building in Dessau, Germany, ca. 1931 or 1932. Photo courtesy of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation

Who knew that you could sleep at the Bauhaus? I certainly didn’t when I began planning a trip to Dessau, Germany, to see its legendary school and architecture. But a few weeks later, there I was inside the Arndt studio, taking in the view of rooftops and sky through the same massive half-wall of windows that architect Alfred Arndt and photographer Gertrud Arndt once stared through.

The couple, along with Franz Ehrhlich, Marianne Brandt and Marcel Breuer (whose tubular steel furniture still adorns many of the rooms), were among the Bauhaus visionaries who inhabited the studio building’s coveted student ateliers during the school’s heyday. Today, these spaces are bookable accommodations, but the light-filled studios maintain the same spirit, with their no-frills furnishings and serene vibe.

“The idea that people working on a shared task, as at the Bauhaus, should have the opportunity to occasionally and undisturbedly withdraw from the community, led to the students’ atelier building being removed from the rest of the workplaces,” Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius said in 1930, “and to giving each atelier the greatest possible peace and each its own small balcony.”

Our intrepid writer slept in the Arndt Room, which was the quarters of Alfred and Gertrude Arndt when they were Bauhaus students. Photo by Yvonne Tenschert

It’s this one-of-kind atmosphere that sets the tone for the Bauhaus experience in its entirety. The Bauhaus building as a whole — now home to the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation — has the feel of its own little community within a community. (“A lot of our research is focusing on material studies, colors and traces of the various renovations in the past 90 years,” says director Claudia Perren.)

You can stroll around the grounds, as I did, to get the full perspective of the building. You can also have breakfast, lunch or dinner at the café bistro or a midday meal at the original canteen, and then head out at your leisure to explore the other architecture sites.

After all, Dessau, where Gropius was able to most fully realize his motto of “Art and Technology — A new Unity” is home to more original Bauhaus buildings that any other city in the world. It’s a thrill to walk in the footsteps of Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Josef Albers and so many others who shaped design, architecture and modern living.

“Although it was only a short period of time, the impulses for modernity and functionalism that were set during this period are still influential today,” says Frank Landau, a Bauhaus specialist who has an eponymous gallery in Frankfurt. “Even now, designers are faced with the task of merging aesthetics and functionality. Of course, new impulses have been set ever since, and of course the design is constantly changing, with one difference — the Bauhaus remains modern.”

The Bauhaus Building

Photo by Tadashi Okochi © Pen Magazine

For this design lover, seeing the famous Bauhaus logo on the former school building’s southwest side was something akin to seeing the Eiffel Tower for the first time. My elation continued when I rounded the corner and came face to face with the famous glass-curtain wall, through which the underlying construction is visible. The grid of small panes became a defining aesthetic for this modernist icon of glass, steel and reinforced concrete.

Following the Bauhaus’s move from Weimar, where Gropius founded the school in 1919, to Dessau in 1925, the then-industrial city commissioned him to design the new building on a municipal plot.

The four-story asymmetrical wings comprise the workshop wing, which today houses exhibition spaces, the visitors’ center and the café; the north wing, where the technical school resides; and the studio building, in which Brandt’s former atelier has been kept in its original state, complete with furniture by her classmate Breuer.

Photo by Tadashi Okochi © Pen Magazine

Including joinery, weaving, metal, wall painting and typography, the Bauhaus workshops were behind most of the building’s furnishings. A skybridge, appearing to float above the ground, connects the workshop wing and the north wing and has a replica of Gropius’s office, which he occupied until his departure in 1928.

A single-story building just beyond the bridge links the workshop wing to the studio building, and it houses the auditorium and canteen. I spent a lot of time walking around the building, both inside and out, discovering all of its design details, from its subtle color accents to its sunny vestibules to how light changes the appearance of its facade throughout the day. It’s true what Gropius said: “The observer was to go all around this building to comprehend its corporality and the function of its subdivisions — there is no central aspect of the building.”

The Masters’ Houses

Reconstructed Masters’ Houses of Walter Gropius and László Moholy-Nagy. Photo by Yvonne Tenschert

Following my first look at the main Bauhaus building and lunch at the café, I headed down Gropiusallee and took a right on Ebertallee, where the complex of Masters’ Houses are located. Set within a quiet wooded plot of pine trees, these four white, cubic forms were designed by Gropius to embody his principles of modern living.

Each house bears the last name of the Bauhaus master who lived there, which included the aforementioned László Moholy-Nagy and Lyonel Feininger, Georg Muche and Oskar Schlemmer and Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, some of whom departed from Gropius’s design by adding interior colors that harmonized with their work.

Together comprising the quintessential artist colony, these homes — modular juxtapositions of horizontal and vertical lines with strong interior-exterior connections — were later occupied by the Alberses, the Arndts and Mies van der Rohe. (The Gropius house is a contemporary interpretation of the original, which, along with the Moholy-Nagy house, was destroyed in World War II.)

The Pump Room (Trinkhalle)

The Pump Room, or Trinkhalle, designed by Mies van der Rohe. Photo by Yvonne Tenschert

Built into the wall surrounding Gropius’s own Master House, this refreshment kiosk was the only building in Dessau realized by the third and final Bauhaus director, Mies van der Rohe. Although today’s structure is a contemporary interpretation (the original was demolished in 1962), it maintains the same clean form that seamlessly blends into the wall.

Kornhaus

Kornhaus, designed by Carl Fieger. Photo by Doreen Ritzau

After my visit to the Masters’ Houses, I headed down the street to the Kornhaus. (If you’re not up for the walk, look out for the Bauhaus bus.) Situated in a pleasant spot on the bank of the Elbe River, the curving building was designed by Carl Fieger in 1929.

Feiger worked as a draftsmen in Gropius’s firm, and taught technical drawing and descriptive geometry at the Bauhaus between 1927 and 1930. He also played an integral role in the planning of the Bauhaus building and the Masters’ Houses.

If you come upon the Kornhaus from the east side, like I did, it doesn’t look much at first. But when you come around the back to the west side, you see that the area that was originally supposed to be an open balcony is now a striking semi-circle covered in paned glass. On the back terrace, which faces the water, the original mushroom-shaped ferroconcrete dome still stands. A semicircular terrace down by the water offers an inviting place to cool off in summer.

Dessau-Törten Housing Estate

Walter Gropius-designed housing in the estate. Photo by Yvonne Tenschert

Slightly farther afield is this terraced housing estate, which was the Bauhaus’s solution for cost-effective mass residential living. Composed of three different housing types, Gropius’s light-colored homes included a garden to grow food and keep livestock.

His two-sectioned Konsum building (today a visitor center and exhibition space) functioned as the center of the estate. Providing an opportunity for the Bauhaus building department to experiment with housing construction, the estate is also home to a brick complex called Houses with Balcony Access (1929–30) by the second Bauhaus director, Hannes Meyer; a prototype of the Steel House by Georg Muche and Richard Paulick (1926–27); and the round-meets-boxy Fieger House (1927), by Carl Fieger.

Bauhaus Museum Dessau

A rendering of the Bauhaus Museum Dessau, set to open next year. Courtesy of © Gonzalez Hinz Zabala

In 2019, Bauhaus will mark 100 years since its founding. Festivities are planned in the three major Bauhaus cities — Weimar, Berlin and Dessau — and there will also be new museums opened in each location, including the Bauhaus Museum Dessau, which is set to open next fall.

The new museum, designed by Barcelona-based architects González Hinz Zabala, will display the second-largest Bauhaus collection in the world. Its 40,000-plus items include early furniture by Breuer, the main estate of Meyer, architectural drawings by Feiger and photocollages by Brandt, ensuring that the Bauhaus legacy will live far into the future.