August 29, 2021Given the diversity of the Chinese art scene, compressing 100 years of its recent history into a representative selection of 100 artworks is no mean feat. But this is exactly what two collectors, Hong Kong’s Adrian Cheng and Paris-based John Dodelande, have done in a new book, Chinese Art: The Impossible Collection, published by Assouline.

The powerful works featured in this hefty tome range from paintings by China’s modern masters, like Zao Wou-Ki and Chu Teh-Chun, to avant-garde pieces by the most exciting and provocative contemporary practitioners in a variety of media — including video and installation — such as Cao Fei and Zhao Zhao.

Most of the art is drawn from the past 30 years or so and thus reflects and responds to the enormous social, political and economic changes experienced in China during its emergence as a global superpower. Providing context and analysis are essays by experts like Philip Tinari, director of the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, making this book essential reading for connoisseurs and collectors alike.

Author Dodelande describes it as an “idealized tour of the Chinese contemporary landscape.” Choosing the artists was like “plotting stars, or placing markers in the landscape,” he says. “We had to draw attention to the brightest and most eminent and let readers join the dots or fill in the gaps.” This approach, of course, fits with the overarching theme of Assouline’s Impossible Collection, a series of books that bring together dream collections of objects chosen by experts in the field.

The criteria Dodelande and Cheng used to curate their list included how widely the artists were collected by institutions, as well as the works’ critical reception, art historical significance and market value. Addressing the last point, Dodelande explains, “We felt that we could not ignore the market, since — rightly or wrongly — that is one of the measures of the stature of an artist.”

Both Cheng and Dodelande know a thing or two about Chinese art, to say the least. Cheng is the founder of K11 Art Foundation, a Hong Kong–based nonprofit organization that incubates young art practitioners and promotes public art education. Dodelande, a businessman in his 30s, has been growing his collection since 2010, often loaning artworks to institutions and sponsoring exhibitions of his own.

Dodelande is particularly interested in artists born after 1970, because they came of age post-Mao and witnessed China’s economic transformation from a low-cost producer to a global leader in advanced technologies — in addition to all the social and environmental costs of these developments. “They have seen extraordinary change happen in their lifetime, and their art is in part a reaction to that: the excitement, the ambiguity, the disorientation,” he says.

Here, Introspective looks at seven artists included in the book who have shaped the course of Chinese art history.

Zao Wou-Ki

Marrying Eastern and Western painting traditions, Zao Wou-Ki (1920–2013) was the most prominent of China’s mid-century émigré artists. Born in Beijing and educated in Hangzhou, he moved in 1948 to Paris, where he lived most of his life.

Western movements such as Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism left their mark on him, but he also grappled with Chinese genres such as calligraphy and brush and ink, incorporating them with different emphases throughout his career.

Works from all stages of his practice — from the gestural, energetic canvases of the 1960s to his later pieces with light and gauzy washes of color — are highly sought after by international collectors.

Chu Teh-Chun

Another key Chinese-French figure in China’s modern art history is Chu Teh-Chun (1920–2014), who was known for Western-style abstract compositions rendered in bold hues. Born in Hangzhou and trained in Chinese painting and oils in his hometown, he moved to Taipei in 1949 and taught there for six years before relocating to Paris, where his career took off.

Chu’s contemporary and friend Wu Guanzhong described his art as “like Western paintings when looking from afar, but when examined closely, they look like Chinese paintings.” Indeed, Chu’s work toggles between worlds: the rugged landscapes of his childhood, American Abstract Expressionism and Chinese calligraphy.

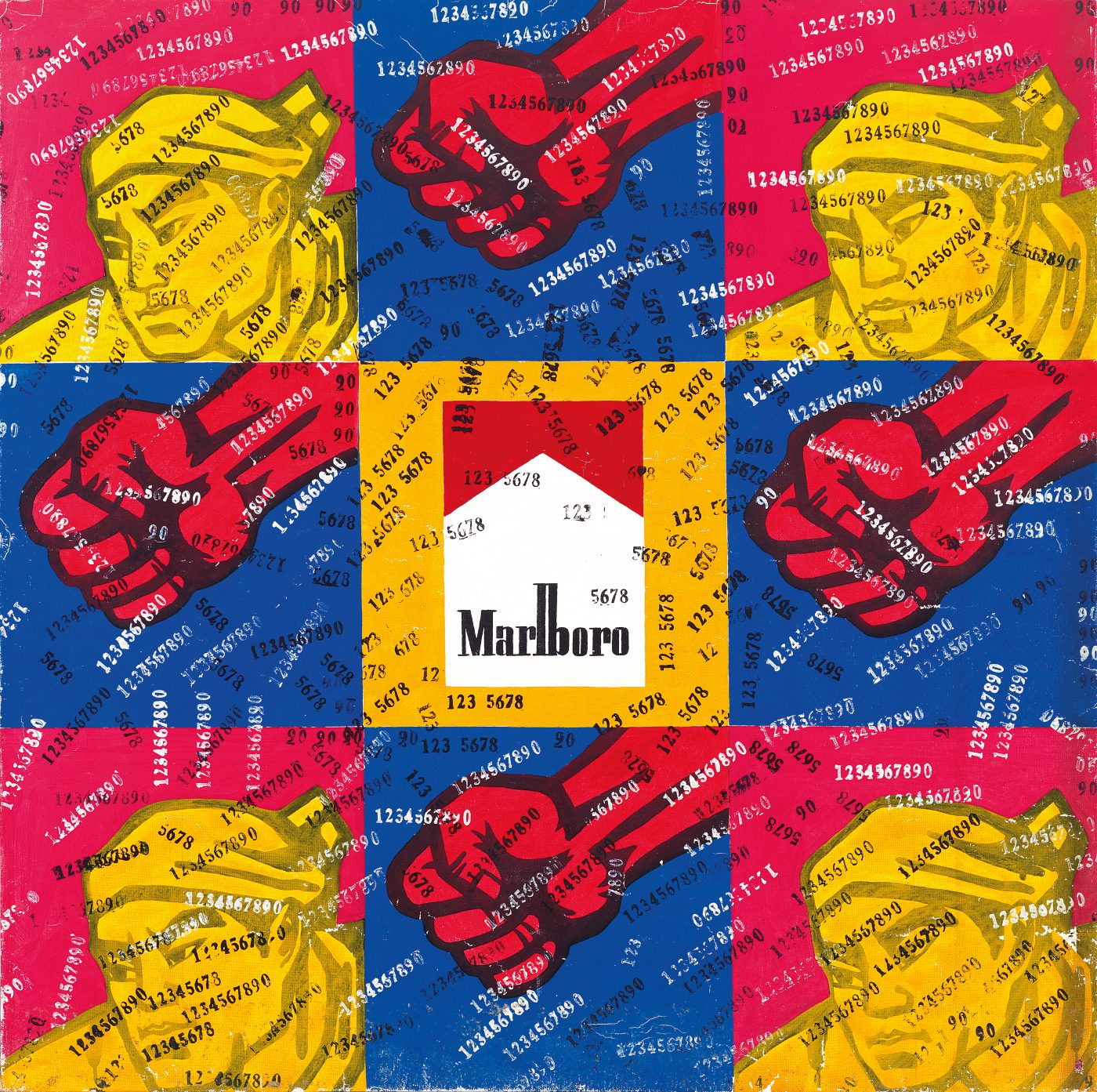

Wang Guangyi

Born in 1957 in Harbin, Heilongjiang Province, Wang Guangyi rose to fame in the early 1990s for his syntheses of Maoist iconography with Western advertisements for brands like Coca-Cola and Marlboro. His most famous series, “New Criticism,” created from 1990 to 2007, dramatizes the opposing forces of Communist ideology and commercialism.

Hailing from the working class, Wang was rejected by several art schools before being accepted by Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, in Hangzhou, in 1984. Now one of China’s most commercially successful talents, he lives and works in Beijing.

Zhang Xiaogang

Family portraits in the style of 1950s and ’60s studio photographs are a recurring motif in ZHANG XIAOGANG’s oeuvre . Rendered in monochrome, the human subjects are stiffly posed and have flat, unreadable expressions. Maoist propaganda often claimed that China was one big family, but these faces suggest the tensions underlying the collectivist ideals.

A native of Kunming, Yunnan, Zhang was born in 1958 and was sent to a reeducation camp in the countryside at the age of 18. In 1977, after the Cultural Revolution, he was accepted into the Sichuan Institute of Fine Arts, in Chongqing. He now lives and works in Beijing.

Yue Minjun

Exuding cynicism, hilarity and grotesquerie, YUE MINJUN’s laughing men rendered in radioactive pink are among the most iconic images of Chinese contemporary art. With large, gaping mouths and tightly closed eyes, these figures appear individually or in hordes, placed in settings that comment on Chinese society and, more broadly, the human condition.

Born in 1962 in Daqing, Heilongjiang Province, Yue trained at Hebei Normal University in the 1980s. During the politically turbulent period leading up to the Tiananmen protests, he began using art to chart the changes taking place in China.

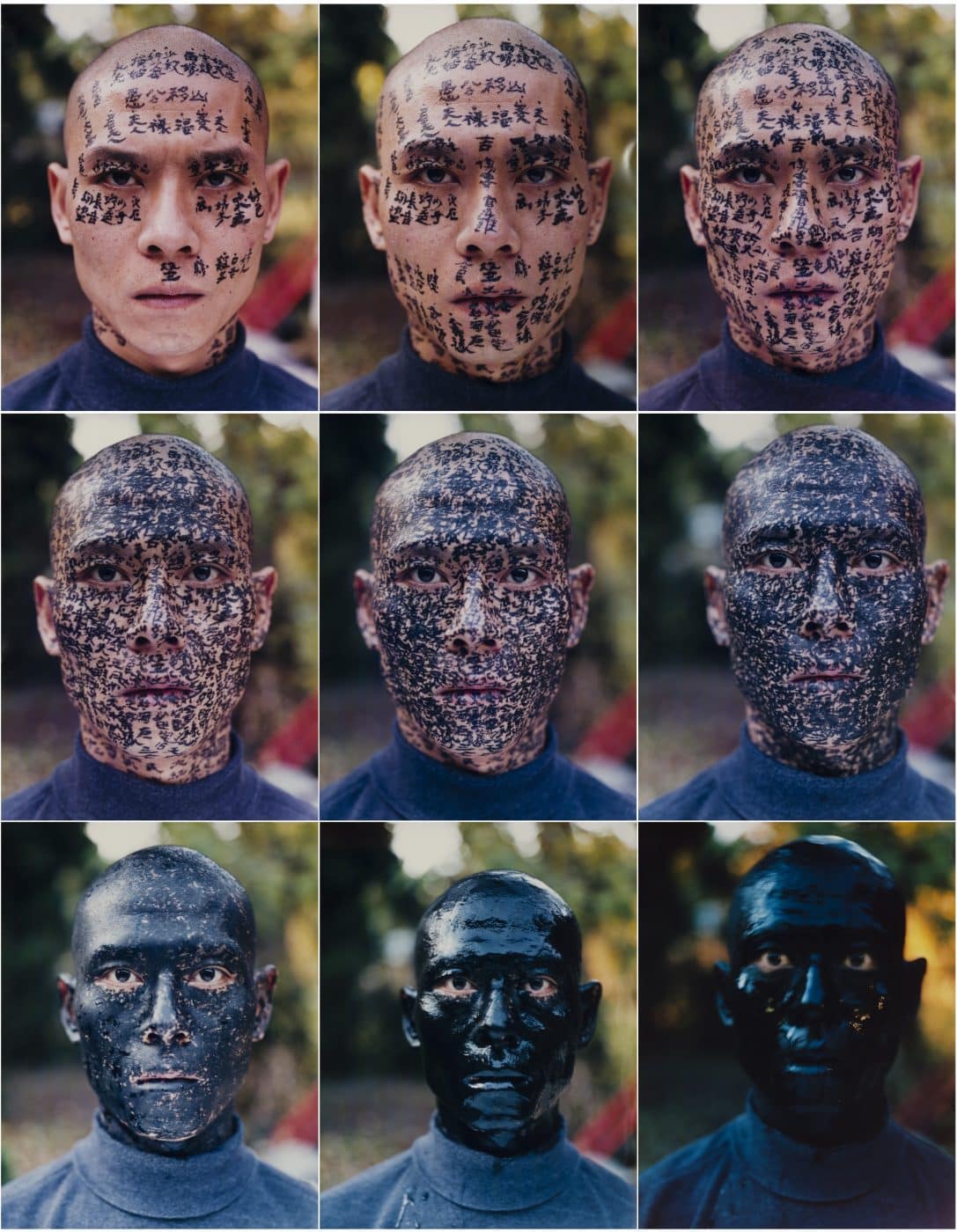

Zhang Huan

Born in 1965 in An Yang, Henan Province, Zhang Huan has an evolving practice that spans performance, photography, installation, sculpture and painting. In the early 1990s, the multidisciplinary artist created visceral performances that tested the limits of his physical endurance and what the authorities found acceptable.

After living in New York for eight years, he returned to China in 2006, set up a studio in Shanghai and started making works reflecting on Chinese heritage and history. Incense ash is a recurring material in his monumental sculptures and paintings exploring themes like spirituality, death and rebirth.

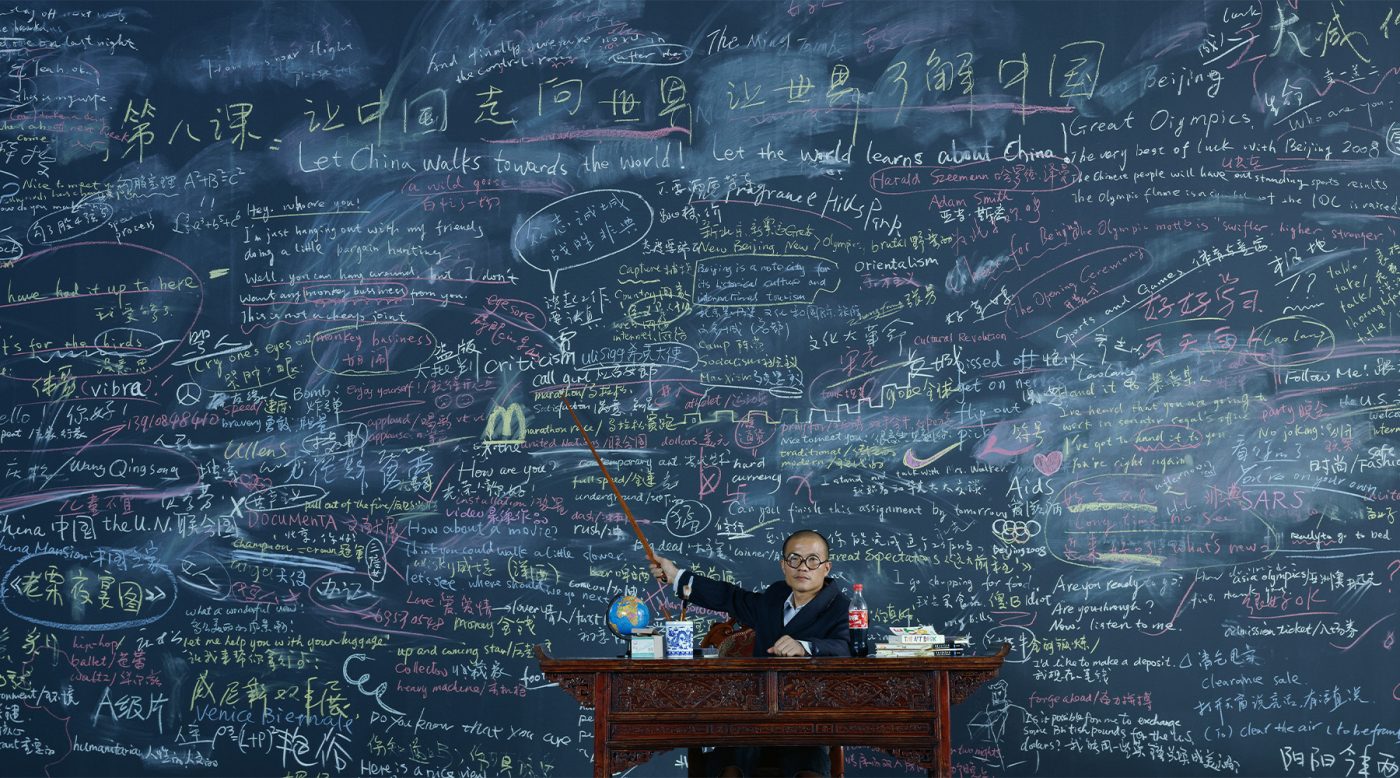

Wang Qingsong

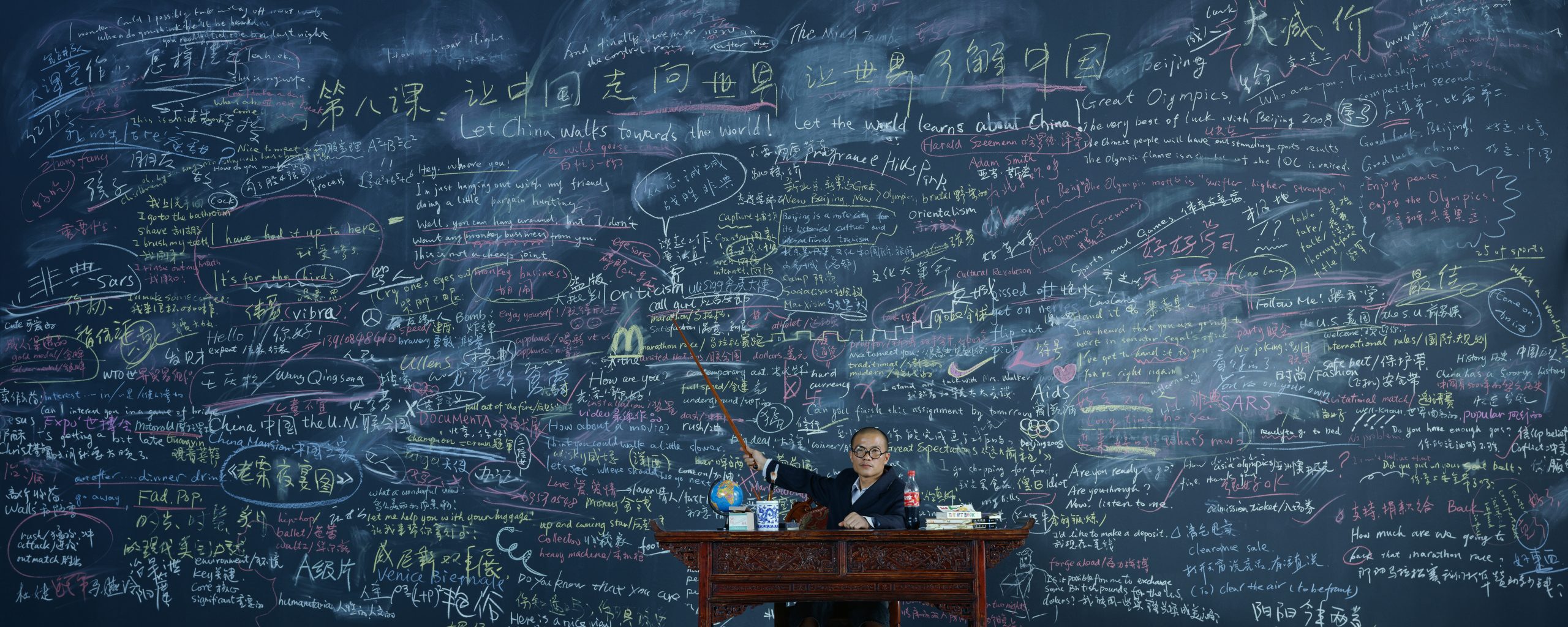

Staging elaborate tableaux involving up to 300 extras, Wang Qingsong creates large-format photographs that critique the rise of consumerism and rapid urban development in China. His mise-en-scènes often refer satirically to canonical Chinese and Western artworks.

Born in 1966 in Daqing, Heilongjiang Province, Wang studied painting at the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts. In the 1990s, he began taking photographs that responded to China’s social changes. Calling himself a journalist, he has said that he does not see his work as conceptual art but as having the attributes of news photography.