January 19, 2025Rarely has an artist had an idea that was more successful than John Chamberlain’s crushed automobile sculptures.

Instantly memorable, they have all the qualities of great three-dimensional art — perfectly balancing weight, color and form — while also being witty: The twisted metal before the viewer is just a rearranged car, after all. They seem to relate both to Pop art, in their reference to American consumerism, and the 20th-century movements toward purely abstract work, while being ultimately sui generis.

But Chamberlain (1927–2011) was multitalented and had much more up his sleeve than his most famous sculptures. “He didn’t want to be defined as a one-medium artist,” says his stepdaughter, Alexandra Fairweather. “Photography was one of his favorite mediums, but people don’t think of him as a photographer.”

Fairweather runs the John Chamberlain Estate with her mother, the artist’s second wife, Prudence Fairweather. They are about to surprise and delight fans of her father’s oeuvre by debuting two lesser-known bodies of his work on 1stDibs, in an online curation called “Paris Rue.”

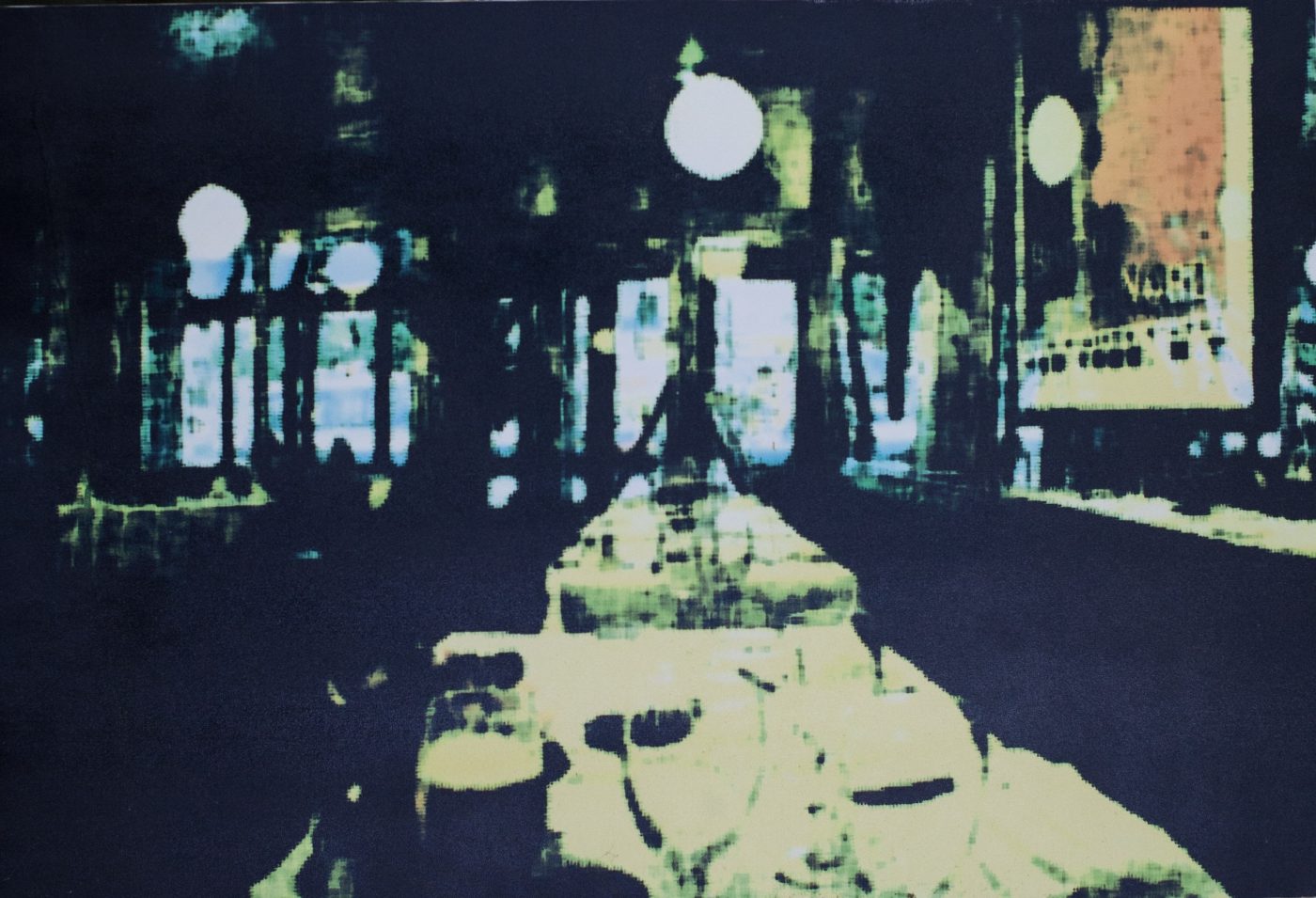

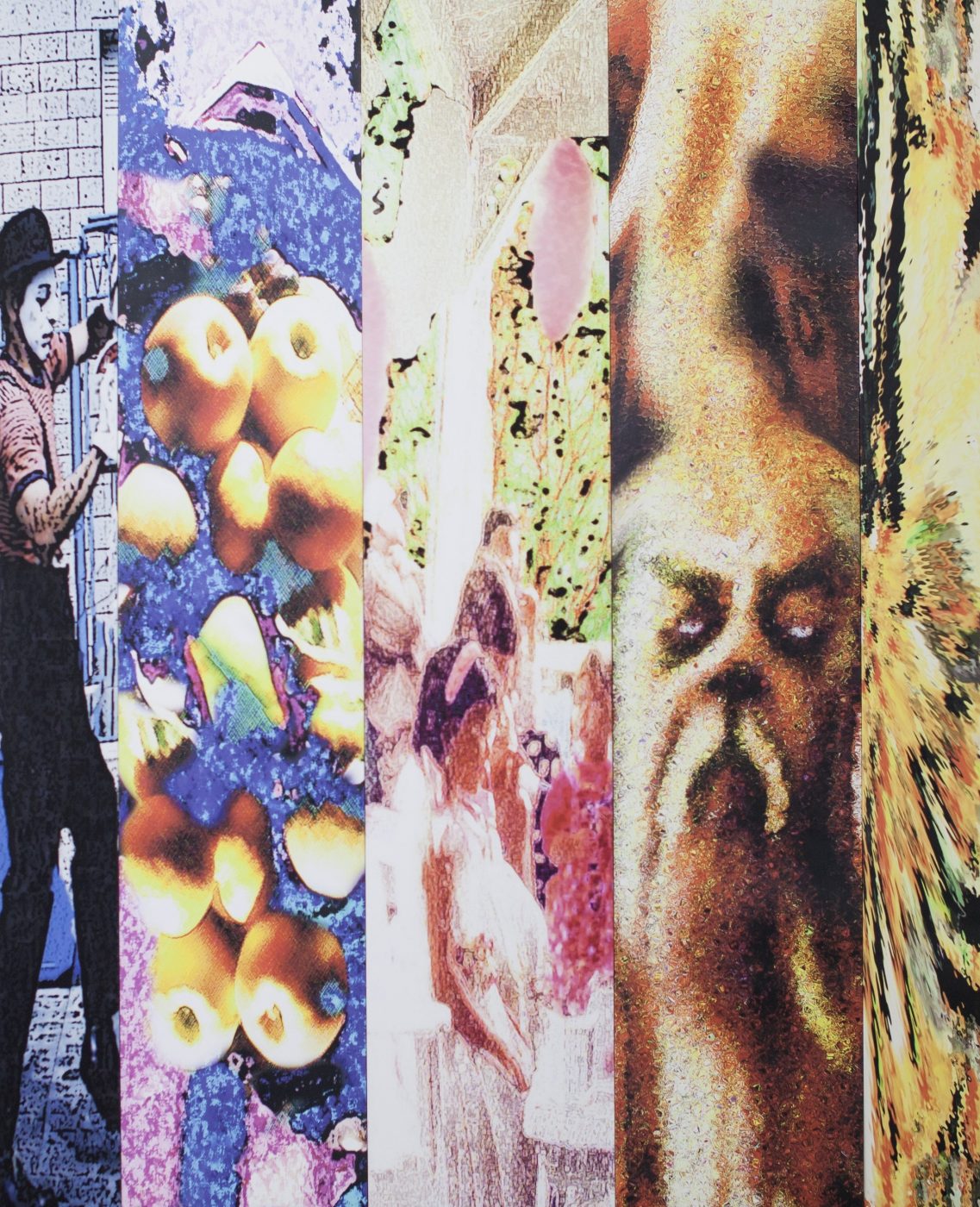

It includes 10 fanciful photographs made with a special Widelux camera and 13 ink-on-canvas works based on digitally manipulated versions of those photographs. There is also one small sculpture, PARISIANSUMMER (2006), made of strips of painted steel arranged in a circular pattern, which almost looks like a flower.

Given the show’s Paris theme, it seems apt that Fairweather sat down to chat with Introspective about the exhibition and her father’s work while taking tea in a glittering salon at the Hôtel de Crillon, one of the city’s iconic historic hotels. She arrived in town for Art Basel Paris and the installation of his sculpture BALMYWISECRACK in the park between the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais.

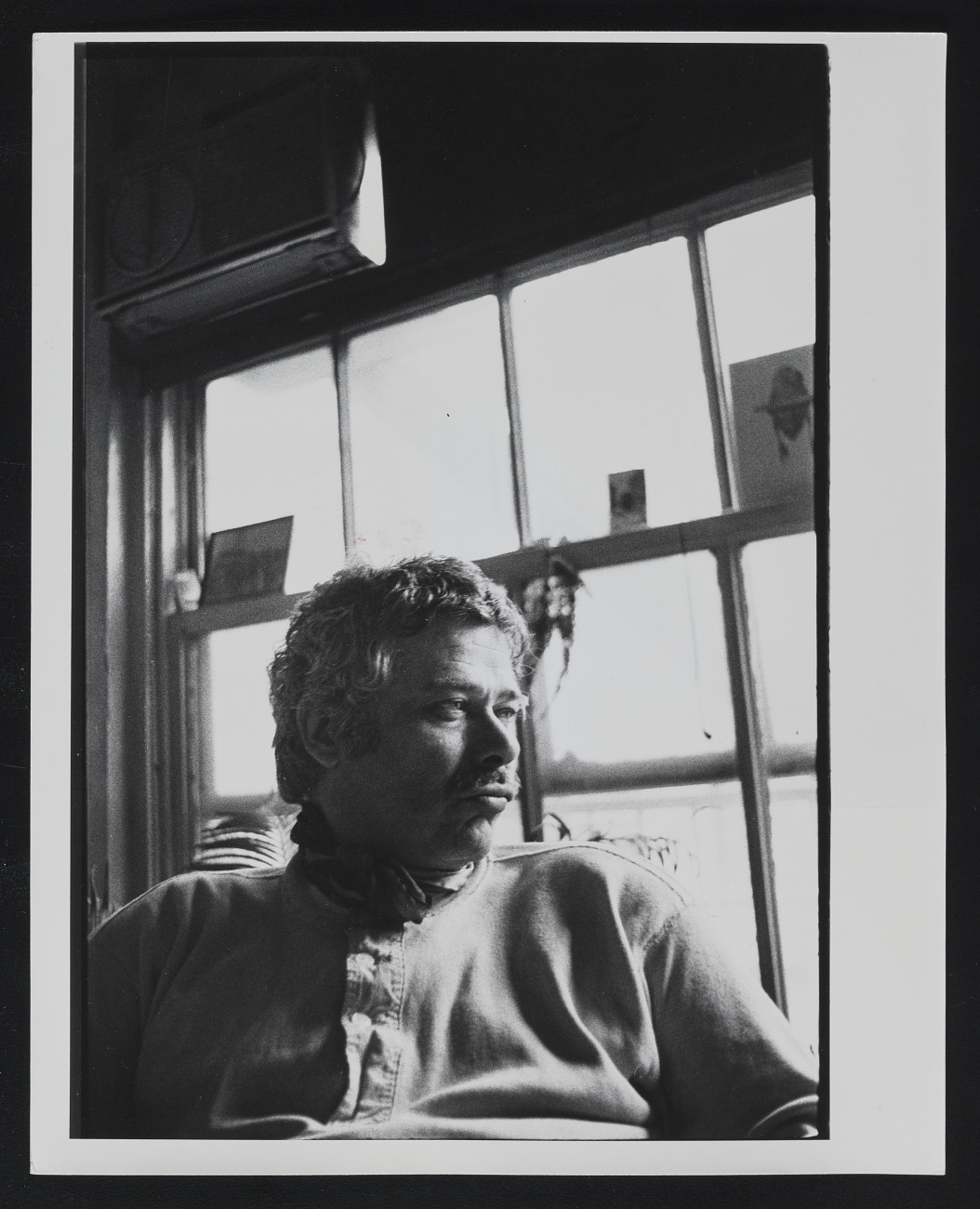

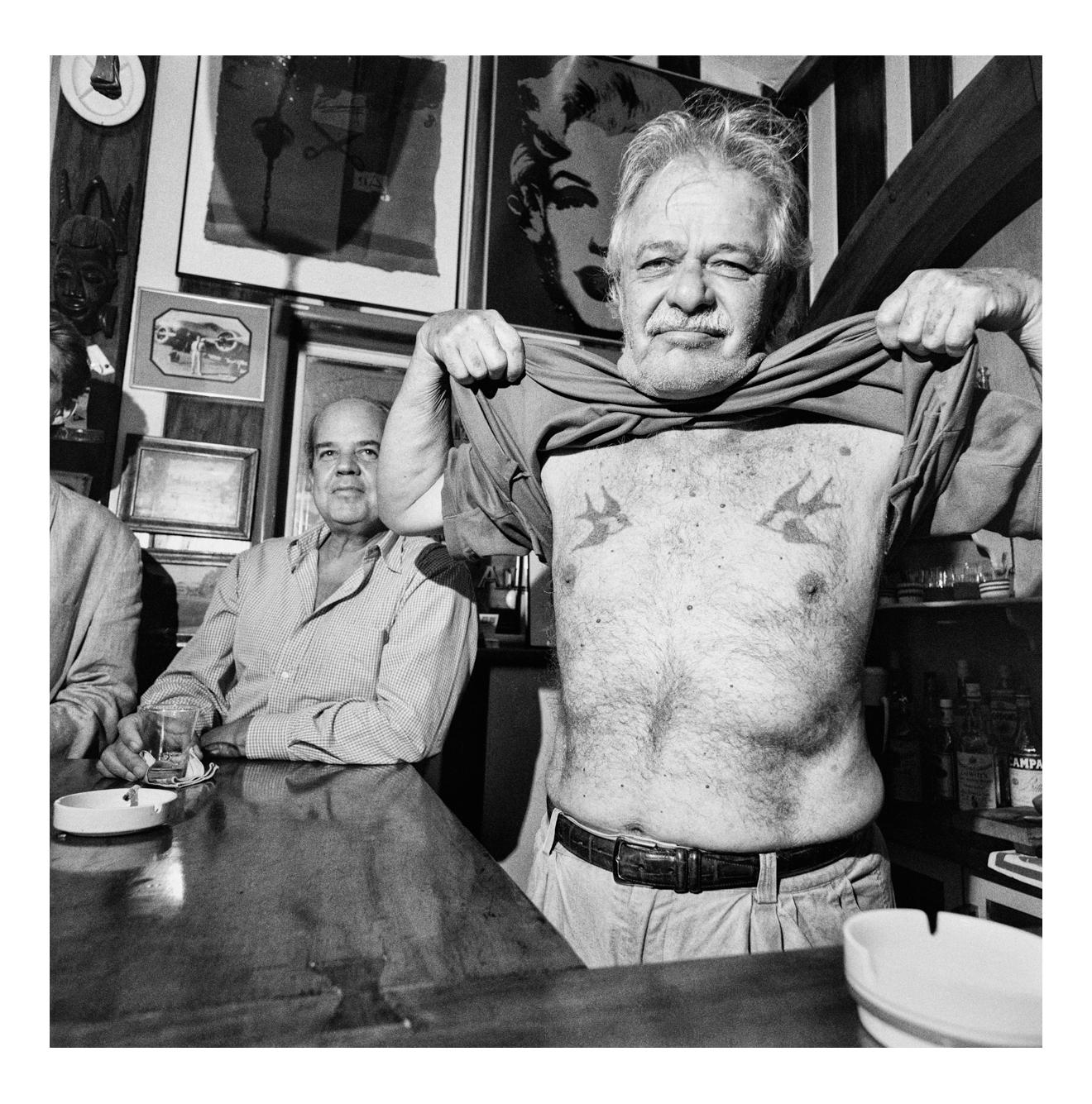

“He loved it here, and he shot a lot of Paris,” says Fairweather. “His photographs were very autobiographical in nature, showing friends, family and his favorite places.” Chamberlain took many images of himself — anticipating selfie culture, Fairweather points out — as well as of his favorite restaurant, Lapérouse, overlooking the Seine, not to mention train stations and street scenes.

The Widelux camera was a typically outside-the-box choice. Images are made by panning horizontally, and Chamberlain’s unsteadied approach produced a distorted, fun-house effect. The resulting pictures are lyrical and whimsical, perhaps not surprising from someone who could find poetry in a smashed-up Chevy. Streaks of light bend and curve through some of the scenes.

Chamberlain followed his impulses in art, and he was spontaneous in the rest of life, too. When Fairweather was a child growing up in the New York area, he would say, “ ‘Okay, we’re going to Paris today,’ ” she recalls. “There was no planning, we would just go — that was the spirit.”

Donna De Salvo, a curator at Dia Art Foundation in the 1980s who is working there again, remembers talking to Chamberlain about the photographs at his compound in Sarasota, Florida. Chamberlain was based in New York and had a large studio on Shelter Island as well as in Sarasota.

“He was never interested in straight photography,” says De Salvo, who has also served as a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York. “It was a tool for him. It’s analogous to metal bending in the way he understands space intuitively.” Her current position at Dia affords a useful perspective, as it has the largest collection of Chamberlain’s oeuvre in the world and specializes in artists of his generation.

“He worked in abstraction for so long,” she says. “But when he picked up figural elements in the photos, they were almost surreal, with just a bit of recognizable image.”

Chamberlain treated the Widelux images as experiments, “almost like sketches,” she adds. “It’s a very Bauhaus way to look at materials.”

That resourceful approach had an unlikely beginning and followed a long, winding road to arrive at the masterful works we’re familiar with today. Chamberlain grew up in Chicago but left home at 16, in 1941, to travel with a friend. “They ran out of money in Nevada,” Fairweather recounts. “They went into a restaurant and ordered everything on the menu, totaling eighty-nine cents.”

Unable to pay the bill, and having had their offer to work it off by washing dishes turned down, they got thrown in jail. There Chamberlain saw a U.S. Army recruitment poster with the classic “I Want You” design featuring Uncle Sam.

“He lied about his age and went into the navy,” says Fairweather. When he got out of the service, he used the GI Bill to study makeup and hairdressing, which he did for several years before deciding to study art.

He enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago but did not graduate, fleeing for the unstructured and bohemian educational pastures of the now famed Black Mountain College in North Carolina, one of the greatest hotbeds of 20th-century creativity, emanating from the likes Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage and Merce Cunningham, among other luminaries who studied and taught there.

He studied poetry at Black Mountain, which Fairweather says inspired the lyrical titles he gave his creations. Chamberlain moved around the country and worked in various places before settling in New York in the late 1950s.

The series that made him famous got its start in 1959 at the Southampton home of a painter friend. “He was at Larry Rivers’s house, and there was an old car, and he decided that he was going to use that old car to make a piece,” says Fairweather. “He didn’t ask Larry first. Really, it was about finding accessible art supplies. He didn’t have any money.” That appropriation resulted in the work Shortstop, which sold at Sotheby’s for $1.8 million in 2013.

It was another Larry — Light and Space artist Larry Bell, now 84 and famous for his glass-box works — who sparked Chamberlain’s interest in photography in 1977, when he was already a mid-career star.

Chamberlain had made several feature films back in the 1960s that starred some of Andy Warhol’s “superstars,” yet another unexplored facet of his long career, but hadn’t really explored still photography until Bell gave him a camera. “After that gift, he was off and running,” says Fairweather.

He began making ink-jet prints based on the Widelux images only around 2000, she says, a late-life tack that shows his restless mind still looking for new ways to elaborate on his ideas. In some of these works, he digitally combined the photographs to create collages of sorts.

Fairweather already has a sense of how the “Paris Rue” show will be greeted. “When people find out these photographs are by him, they’re blown away,” she says. “It just feels like the world is ready to see them, understand them and embrace them.”