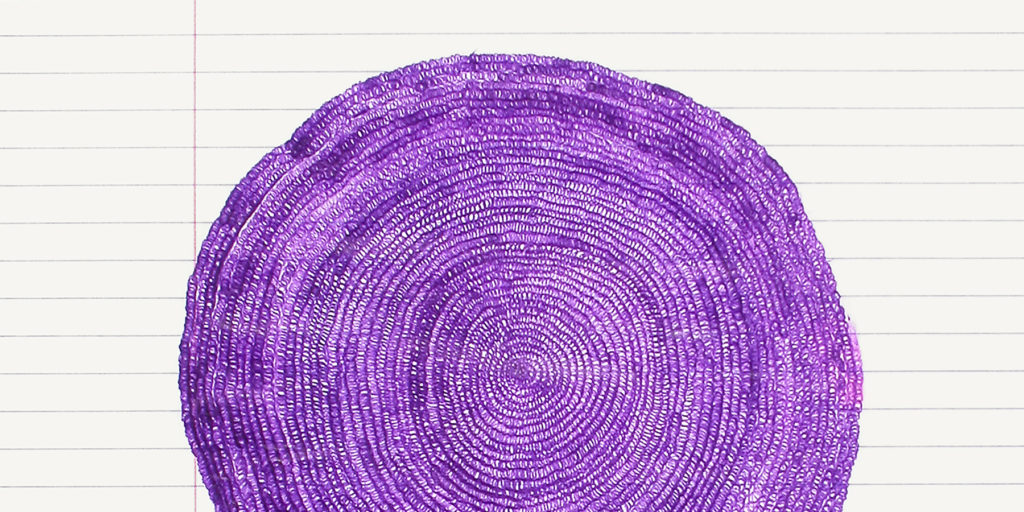

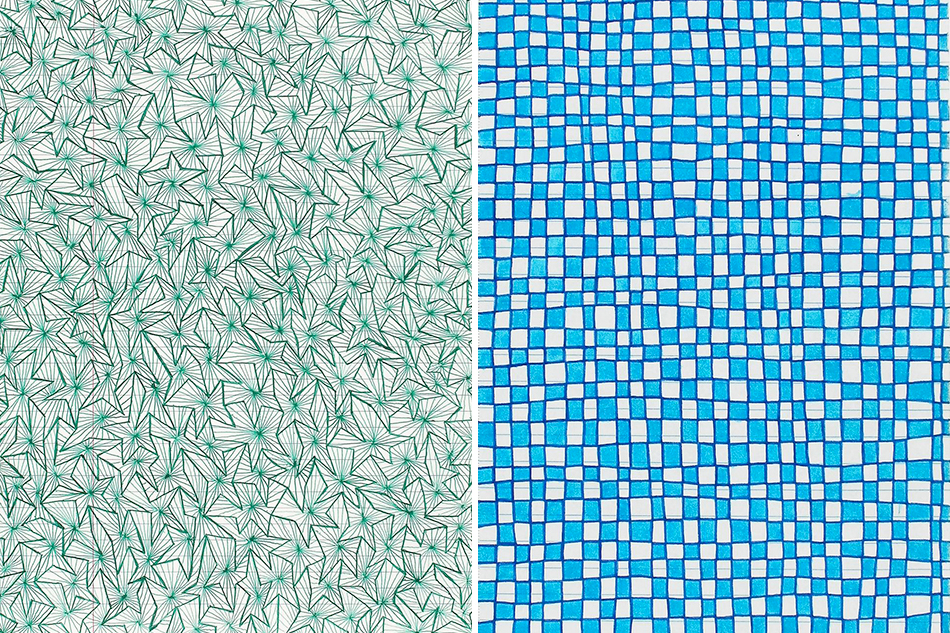

August 29th, 2016In Ballpoint Art, Introspective‘s managing editor, Trent Morse, profiles 30 contemporary artists who push the limits of the ballpoint pen, including Rebecca E. Chamberlain, whose ink painting Johnson Wax Factory Screen, 2008 (detail, above), depicts Frank Lloyd Wright‘s famous complex in Wisconsin. Top: Untitled, 2014–15, by Lori Ellison. All images copyright the artists; courtesy of Laurence King Publishing

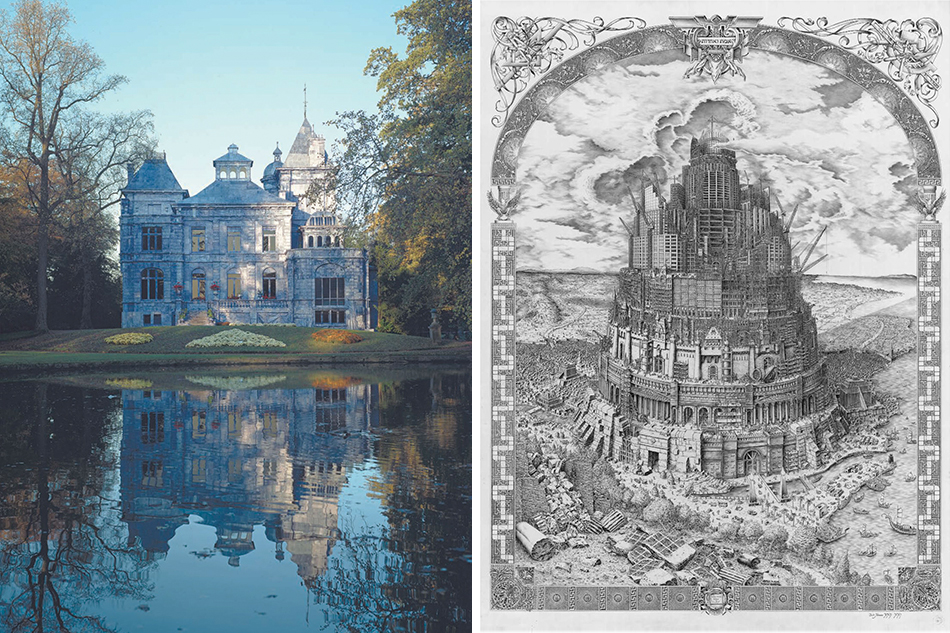

My new book, Ballpoint Art, plays host to 30 contemporary artists (plus many 20th-century luminaries) who perform mind-bending feats with the lowly ballpoint pen. Among the earliest of these are Alighiero Boetti’s 1970s collaborative works, which required helpers making cumulative marks to fill giant sheets of paper with coded messages. In the 1980s and ’90s, Jan Fabre took his collaborations a step further by coating bathtubs, dining tables, sculptures and the outer walls of a Belgian castle in the majestic blue of Bic ballpoint ink, which he likens to lapis lazuli. The Paris-based Iranian artist Ghazel, on the other hand, creates personal performances with ballpoints, covering Persian-language world maps with symbols of displacement until her pen runs dry, leaving unfinished pictographs of houses, tree roots, suitcases and hearts on the map’s surface.

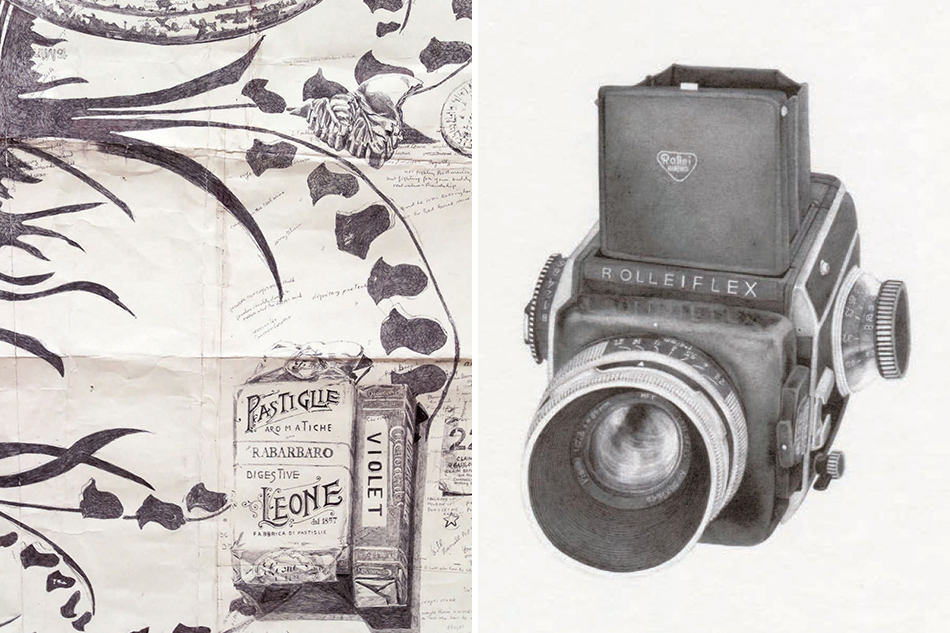

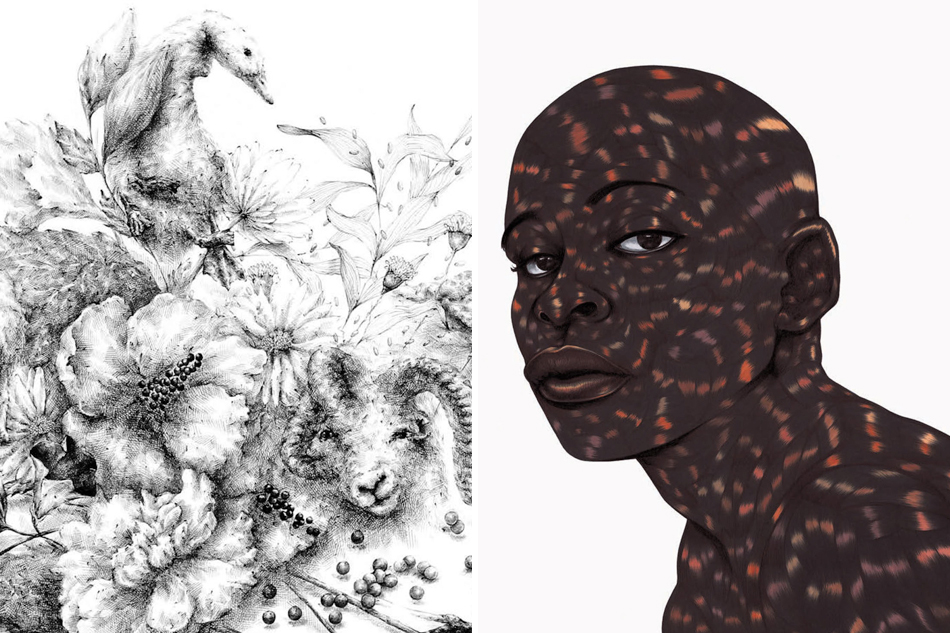

Among the works that could more easily be classified as drawings are strange and surreal compositions by master draftsmen and -women, such as Rita Ackermann, Marlene McCarty, Butt Johnson, Claudio Ethos, Joo Lee Kang and Wai Pong Yu. Meanwhile, Dawn Clements and Renato Orara use ballpoints to draw realistic likenesses of household objects, like gum packets and T-shirts, bringing these ordinary things to life with the equally mundane pens. And Rebecca E. Chamberlain siphons the ink out of ballpoints to repurpose it as paint for her ghostly renderings of mid-century interiors, including Frank Lloyd Wright’s radiant S.C. Johnson headquarters in Wisconsin.

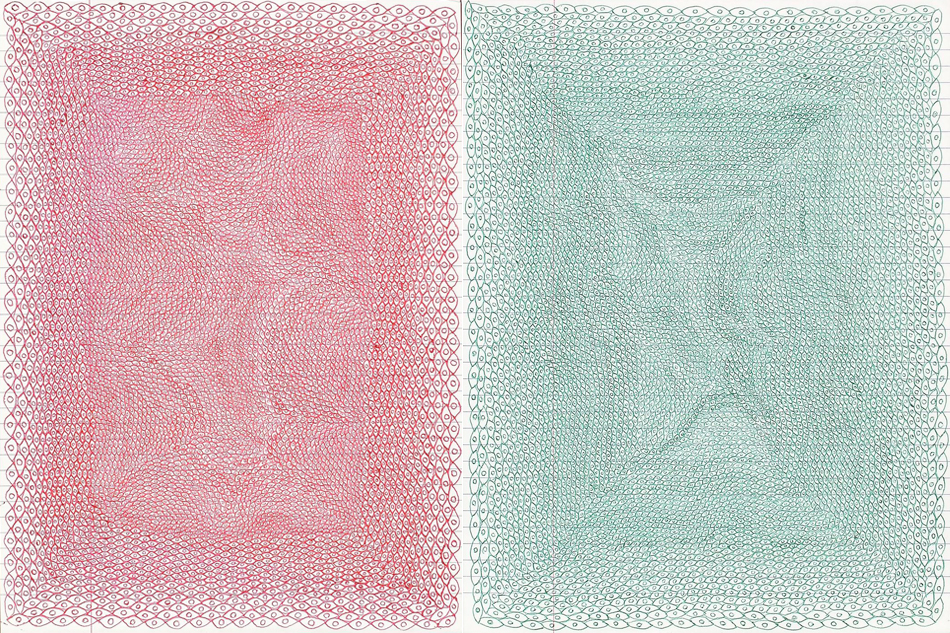

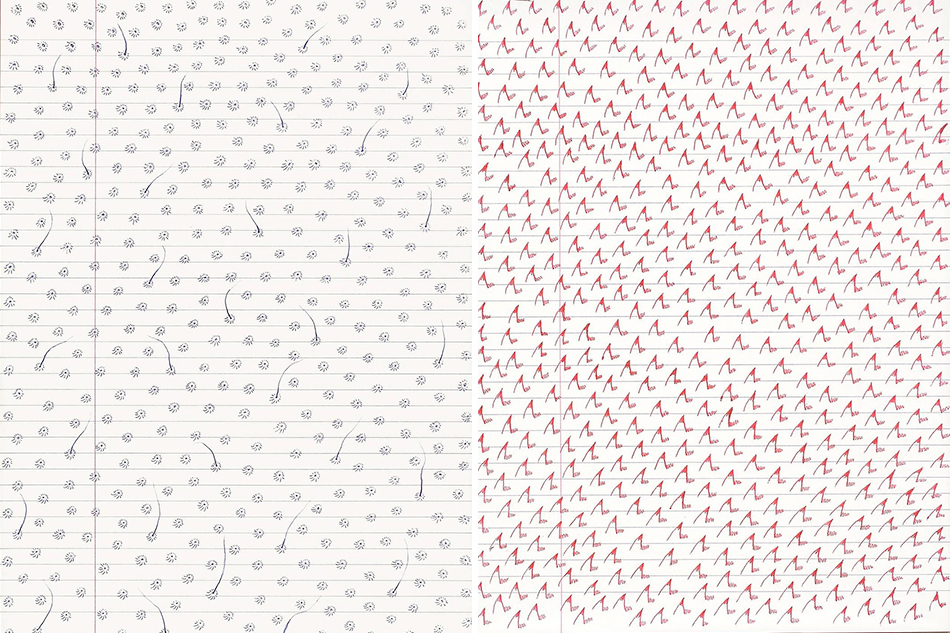

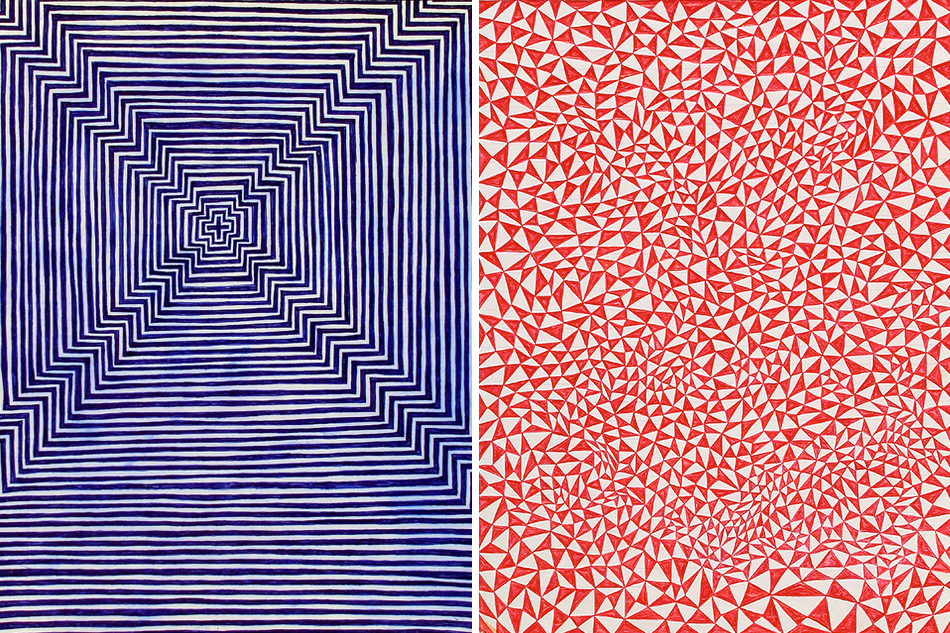

But one artist stands out for her extreme humbleness. Lori Ellison made little abstractions on notebook-size paper and actual notebook paper, often with the ruled lines visible behind the art. She even wrote a short treatise called “On Humility: Or Small Work.” To be sure, her compositions of endlessly repeated checkers, diamonds, triangles, squiggles and cellular shapes are trippy optical illusions that took great skill to make. Yet they also celebrate the limits of ballpoint.

In Untitled, 2010–11, Ellison mingled ballpoint with marker.

Ellison showed the pen for what it is in the hands of non-artists: a doodling device. She usually worked in only one or two colors at a time, although she was a prolific painter as well as a drawer, having earned a BFA from Virginia Commonwealth University and an MFA from Temple University before settling in New York and finding representation from McKenzie Fine Art.

Ellison almost didn’t make it into Ballpoint Art. I’d long been aware of her work, but by the time I sent my final list of international artists to my London-based publisher, Laurence King, I already had too many Americans on the roster. Still, her name kept coming up whenever I mentioned that I was working on a compendium of ballpoint art. New York artists and art lovers would say that I must include her. And I’m glad I did. I spoke to Ellison in the spring of last year, a few months before she died of cancer, at age 56. She leaves behind these insights into her ballpoint drawings, as well as a quietly powerful body of work.

How did you start using ballpoint pen, in your life but especially in your artwork?

I started using ballpoint pen when I was a teenager in school, I believe, though it could have been earlier. When I was in graduate school, I would spend so long on these dense five-foot-by-three-foot paintings that the motifs of the drawings would appear before my eyes when I went to bed at night. So I found myself doodling with ballpoint pen in my notebook. When I first came up to New York, I didn’t have studio space, and so I concentrated on the drawings. That makes a nearly twenty-year commitment to ballpoint-pen drawings.

How does the pen itself shape your abstractions of repeating patterns?

It has turned out to be a remarkably adaptable medium — I can do so many different things with it. I find that ballpoint pen can make a very fine line, and then I can layer it to get the width and consistency I want. There is always that small lack of control that keeps things interesting.

Untitled, 2007, is one of Ellison’s more organic abstractions.

What is your process? Are your drawings plotted and laid out, or sporadic and “automatic,” or something in between?

They are controlled spontaneity. I never know what either my paintings or ballpoint-pen drawings will look like until I finish them.

How does ballpoint pen compare with other mediums you use?

I go back and forth between painting and drawing. A long period of drawing will move into painting for a long time. I like gouache’s sensuality and the ballpoint pen’s directness.

What kinds of pens do you use?

Paper Mate, always. In blue, green, red and purple. I swore a long time ago that I never would use black, and then I remembered how engaged I have been with Ad Reinhardt [the abstract painter who was famous for his all-black canvases].

Is it possible to correct one of your ballpoint drawings, or do you have to start over after making a mistake?

I would have to start over, but that rarely happens.

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore