September 29, 2019Artists’ reputations wax and wane. Only a few names boast a constant level of interest and admiration from the public, the market and the critical community — and even in these cases, art viewers enjoy looking away for a while and then, lo and behold, “rediscovering” a body of work.

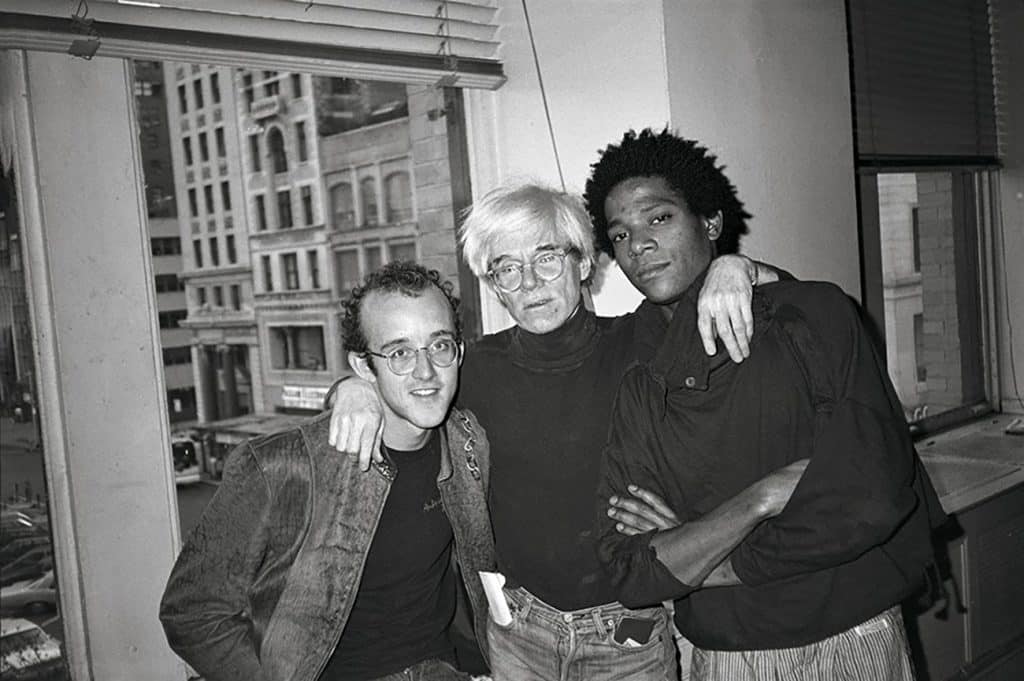

We are certainly living in such a moment of Basquiat mania, judging by the artist’s recent museum shows and auction records. The just-published Warhol on Basquiat: The Iconic Relationship Told in Andy Warhol’s Words and Pictures (Taschen) is but one more example.

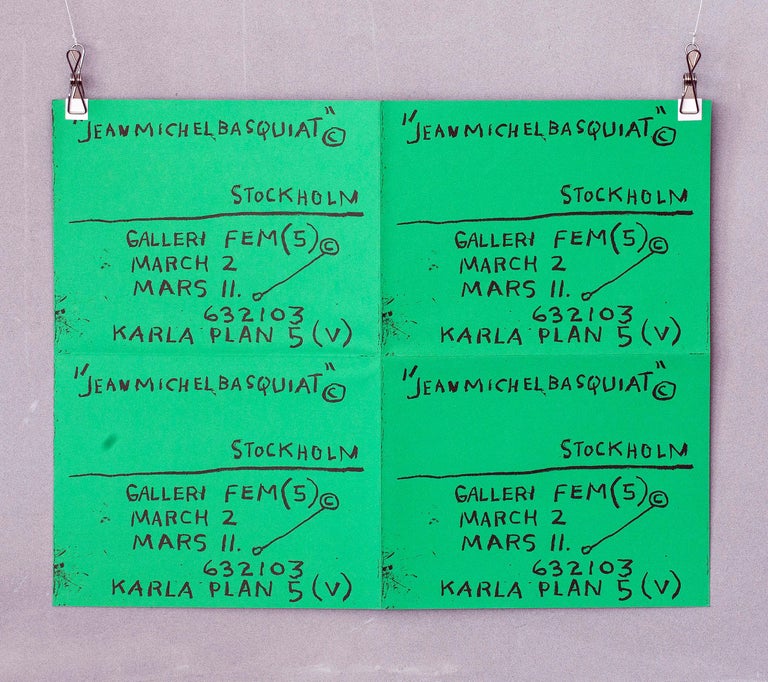

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–88) burned white hot during his short life, producing by one estimate some 900 paintings and still more works in other media. He rose from being a poet and graffiti artist who sometimes slept in a box in a park to the most sought-after artist in New York and Andy Warhol’s collaborator slash best friend.

Basquiat was among the first black artists to establish a top-level name in the market and with museums; he was included in the Whitney Biennial in 1983, when he was 22.

His large, riveting canvases were expressionistic but also somewhat Pop, filled with graffiti-like signs and symbols, mixing mysterious text and images. He wasn’t contained by any known categories: He was sui generis.

“He’s this incredible genius who cuts across cultures and categories — a poet, a musician, a writer, a performer,” says the private art adviser Liz Klein, of Reiss Klein Partners, who has worked in the past for billionaire collector Ronald Lauder and has bought more than one Basquiat canvas on her clients’ behalf over the years. “He created a unique and individual language, something musical and rhythmic, building on expressionism and AbEx, but also cave paintings at Lascaux.”

Eventually, the strain of containing multitudes took its toll in the drug use that killed him. Basquiat can be seen as representing the excesses of the 1980s, how the world could chew someone up with instant success. But his early death seems to have only burnished his reputation. His sense of style, bisexuality and general flouting of convention also offer entry points today for people to see what they want to see.

His myth has been well established for decades, but his current zeitgeist moment seems to have started in May of 2017, when Sotheby’s sold a roughly six-square-foot untitled painting from 1982 to a Japanese buyer for $110.5 million, which remains an auction record for an American artist. (His previous auction high was $57.3 million.) Anyone who wasn’t paying attention to his work before was now.

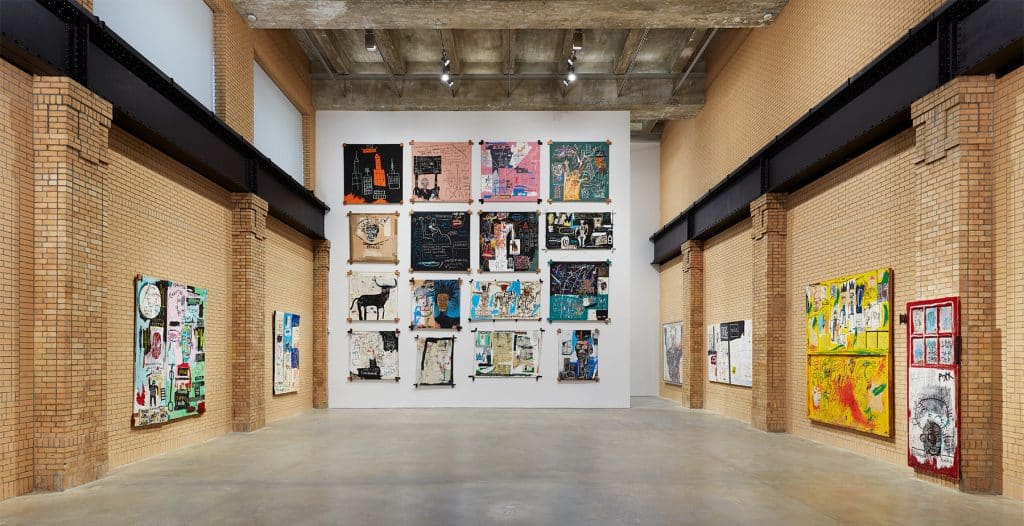

A little more than a year later, the mammoth show “Jean-Michel Basquiat” opened at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, sprawling over multiple floors and allowing for a consideration of his whole oeuvre.

A version of that exhibition appeared in New York this past spring, inaugurating the boffo new East Village space of the Brant Foundation (collector Peter Brant was an early buyer of the artist’s work), in a soaring former power plant off Avenue A. Fittingly, the show took place in the center of the neighborhood where the artist gained fame and spent most of his short adult life.

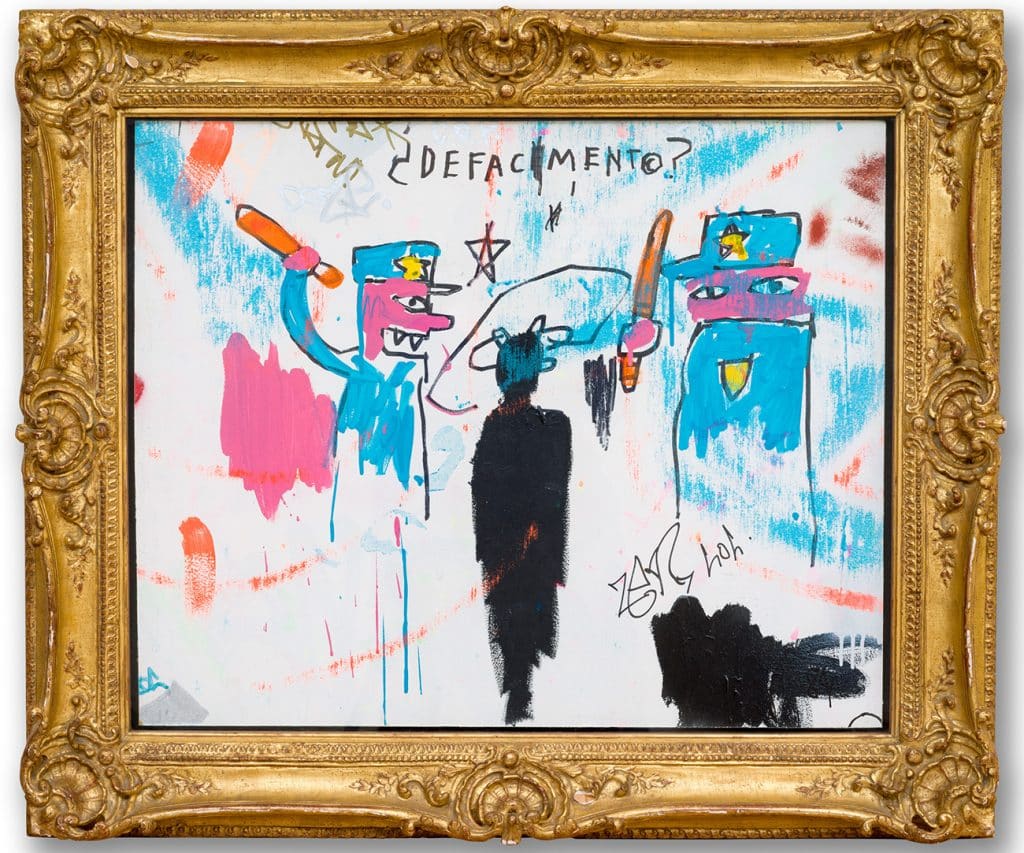

On view until November 6 at the Guggenheim Museum is yet another show, a small one: “Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’: The Untold Story.” This deep-dive exhibition focuses on the 1983 work The Death of Michael Stewart.

Stewart, a young black artist and a student at Pratt Institute, died at the hands of New York City Transit Police after allegedly tagging a subway station. The incident shook Basquiat and many of his peers — the show includes works that touch on Stewart’s death by George Condo, Keith Haring (in whose studio Basquiat painted his version) and David Hammons. Michael Stewart was the rare large-scale Basquiat painting that addressed a political issue of the day, and it feels especially relevant now, given the protests and controversies around the killings of black men at the hands of police in Staten Island; Ferguson, Missouri; and elsewhere.

No doubt we’ll continue to see major displays of Basquiat’s work at exhibition and on the auction block. “He’s as much of a blue-chip artist as anyone at this point,” says Alex Rotter, chairman of the postwar and contemporary art department at Christie’s.

Best of all for an auction house, his appeal cuts across collector categories. “Basquiat does not bring a stereotypical buyer,” Rotter says. “I’ve sold [his pieces] to very wealthy late-twenties types, and I know collectors in their eighties who have them.”

Like nearly everyone else, Rotter has high praise for the work, as well as Basquiat’s role as a pathbreaker for black artists, a sort of Jackie Robinson of the art world. But he acknowledges that Basquiat’s early demise is what makes him endlessly fascinating.

“He has the artist myth,” Rotter says, making an analogy to another tortured creator. “Van Gogh wasn’t a better artist than Cézanne. Most people know that he cut off his ear more than anything about his paintings.”

He rose from being a poet and graffiti artist who sometimes slept in a box in a park to the most sought-after artist in New York.

Basquiat’s signature style is by now quite recognizable, which has helped enhance his cachet and his market. “Like any artist, he had good days and bad days, and the work is uneven,” Klein says. “I don’t think the highest prices always correlate to the best work.”

Not that he didn’t hit the heights of artistic achievement. “His best works riff on the past, but they bring art history forward in some way, too,” adds Klein.

Rotter notes that at least lately, the museums that have championed Basquiat are private ones, like the Vuitton; New York’s Museum of Modern Art still does not own a single Basquiat painting, although it has some works on paper. Museum audiences — composed mostly of people who aren’t buying high-priced paintings, of course — have especially responded to shows that document Basquiat’s early years, when he was full of potential in different media and before his tragic fall.

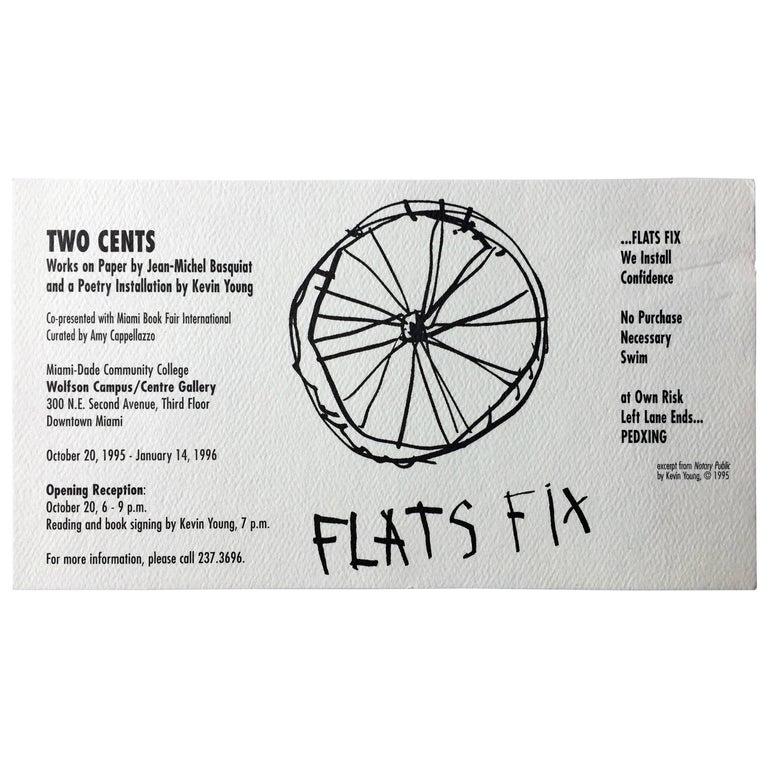

One of those was the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver’s 2018 “Basquiat Before Basquiat: East 12th St. 1979–1980,” composed of works he made while living with girlfriend Alexis Adler.

“He was going in so many different directions all at once,” says Nora Burnett Abrams, the show’s curator and now the MCA’s director, who cites in particular the strength of the writing in his notebooks. “He got channeled into being a painter.”

One of the most appealing aspects of Basquiat’s career, as seen through the lens of today, in our era of working from home, quality time and the rise of “maker” culture, is “the lack of distinction between artistic practice and just living your life,” says Burnett Abrams.

With Basquiat, the elusive quality that people say they’re looking for in politicians and everyone else — authenticity — comes through like a beam of midsummer sunlight. The works in the MCA show, Burnett Abrams says, “had this rush of realness. And that’s why the masterpieces are in such high demand.”