March 14, 2021Earlier this month, fashion brand Chanel proved it could also compete at the most elite level of fine jewelry: The house announced it had cut a rough diamond into a D-color flawless gem with a carat weight of exactly 55.55, in honor of the Chanel No. 5 fragrance, whose centennial is being celebrated this year. An extraordinary lapidary achievement, the stone has been set in a triple-strand diamond necklace.

Although there would certainly be a waiting list of clients for such a special jewel, the firm isn’t selling. “For Chanel, the design and production of this necklace represents a decisive and major step in the history of fine jewelry,” Frédéric Grangié, the company’s president of watches and jewelry, told WWD. “By joining our Patrimoine [the house’s archive] at 18 Place Vendôme rather than being sold, this necklace will forever bear witness to this chapter in the history of Chanel fine jewelry.”

The first chapter in that storied history began at the other end of the materials spectrum, in the costume-jewelry category, with the maison’s founder, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel.

Chanel established her business as a Paris hat shop in 1910 and started selling clothing in 1913. She introduced her costume jewels in the 1920s, when the economy was roaring and fine jewelry was the main mode of adornment among her clients. Fearless about giving offense, Chanel proclaimed, “I love fakes because I find such jewelry provocative, and I find it disgraceful to walk around with millions of dollars around your neck, just because you are rich.”

Then, in 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression, Chanel dramatically switched gears and designed her first and only diamond jewelry collection, Bijoux de Diamants. When the jewels were shown to clients and the press at an exhibition in her Paris home, Chanel explained that her concerns about ostentatious displays had “faded into the background during the economic recession, when, in every sphere of life, there emerged an instinctive desire for authenticity.

“If I have chosen diamonds,” she added, “it is because they represent the greatest value in the smallest volume.”

What she never talked about was the fact that the diamond jewelry was commissioned by the International Diamond Corporation, overseen by Ernest Oppenheimer, who controlled the De Beers diamond-mining company. The organization retained Chanel’s services — providing the gems and paying for the collection’s publicity — to infuse the diamond-jewelry landscape with some excitement during a bleak economic period.

Before the collection debuted, a controversy erupted when the men of the French haute joaillerie industry — among them, representatives from Chaumet, Van Cleef & Arpels and Mellerio — learned that Chanel had been hired for the job. They forcefully expressed their firm belief that a fashion designer, and a female one at that, didn’t have the talent to make important jewels.

At the same time, they were worried that Chanel’s diamond creations would compete with their collections and cut into their profits. They insisted that the pieces be broken up after their initial display. The jewelers’ diamond-buying power gave their demands some weight with the International Diamond Corporation, but the conglomerate decided to proceed with Chanel anyway.

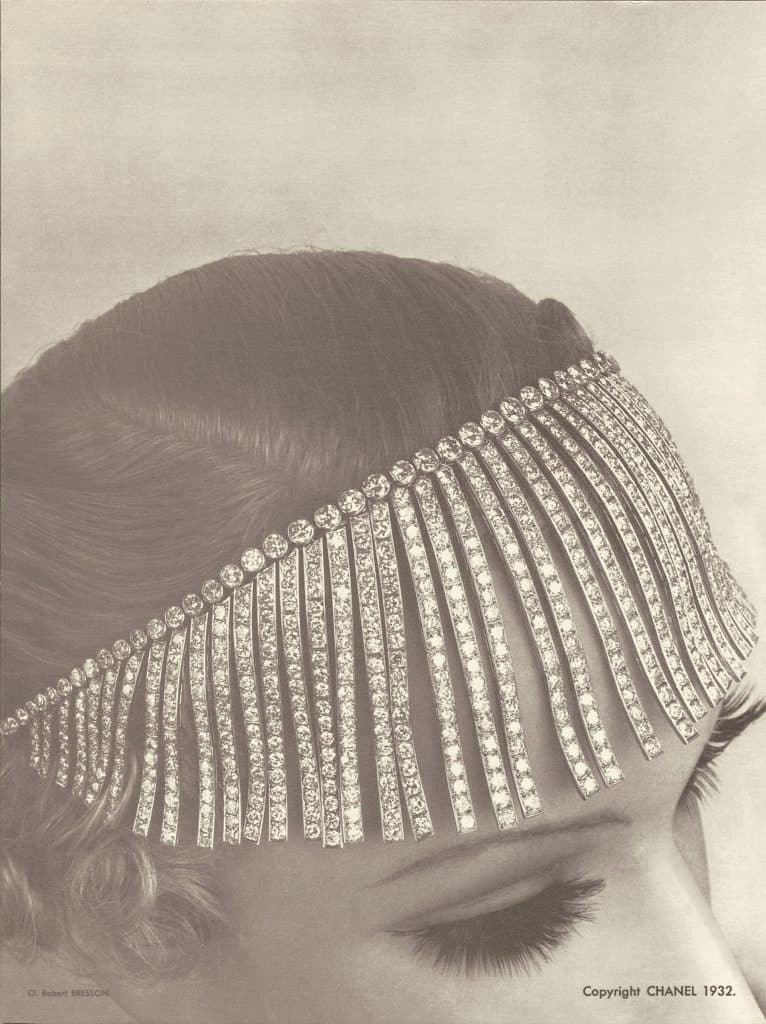

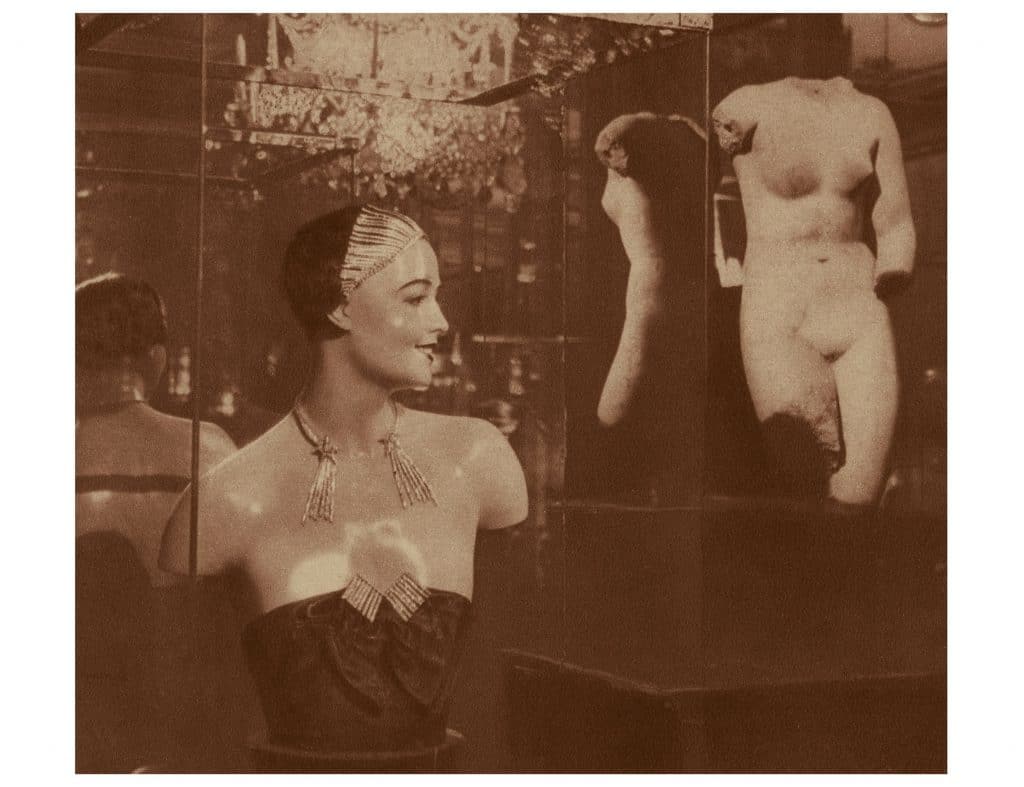

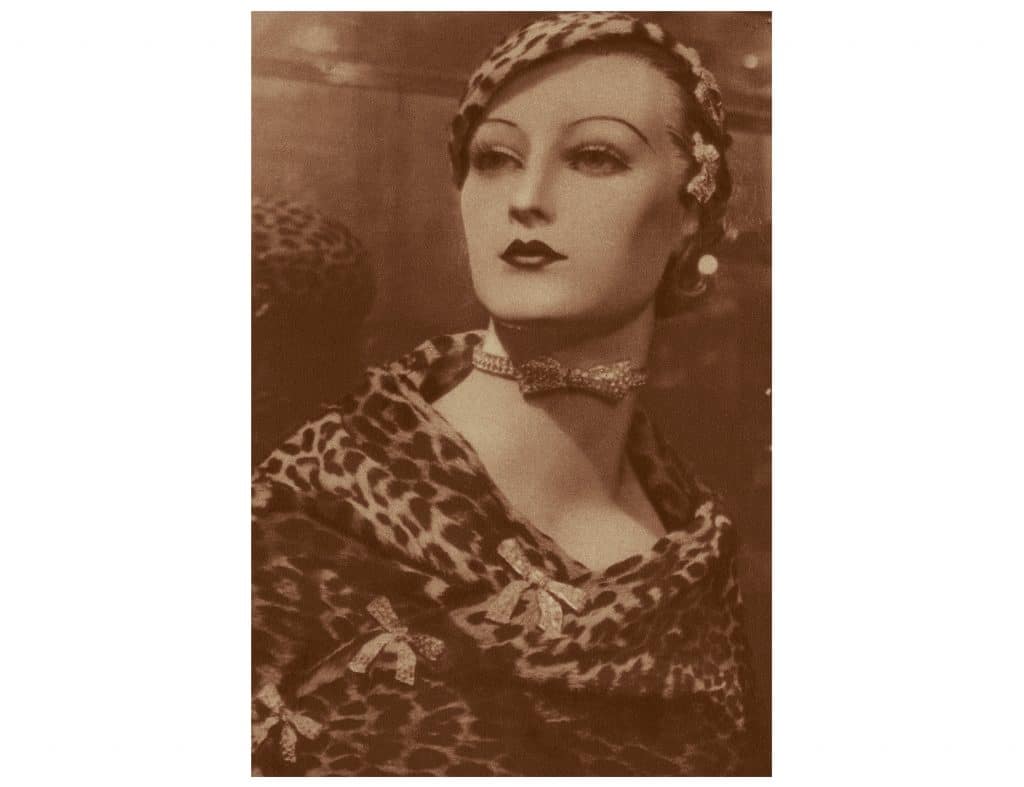

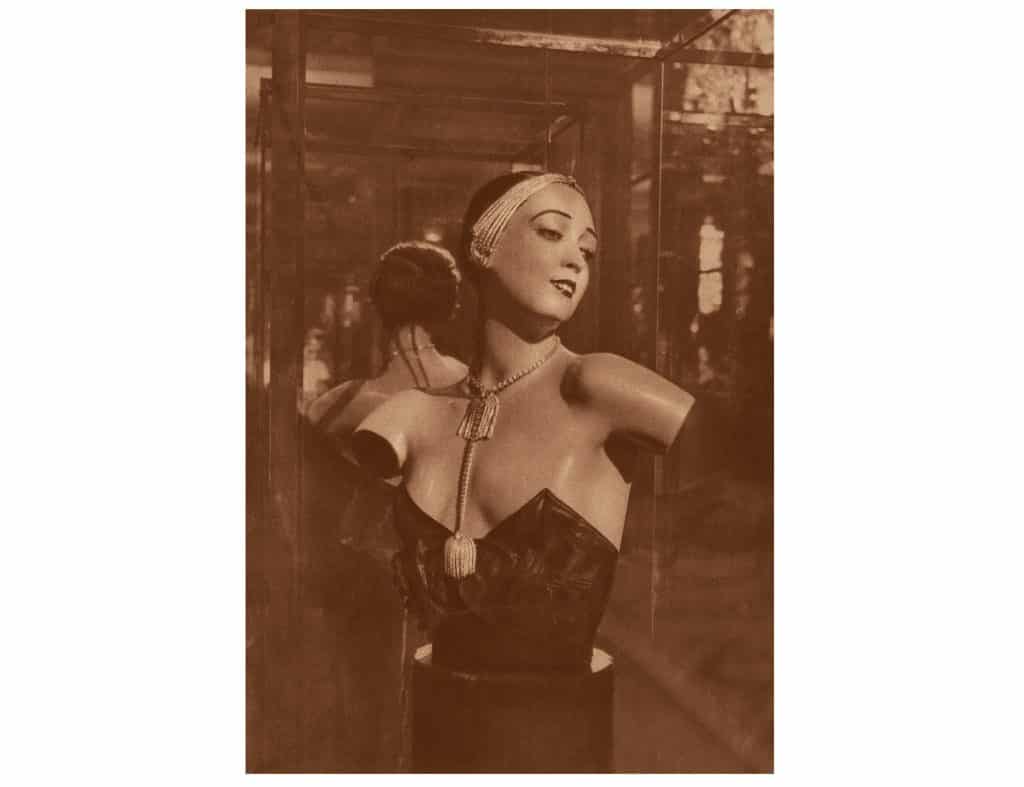

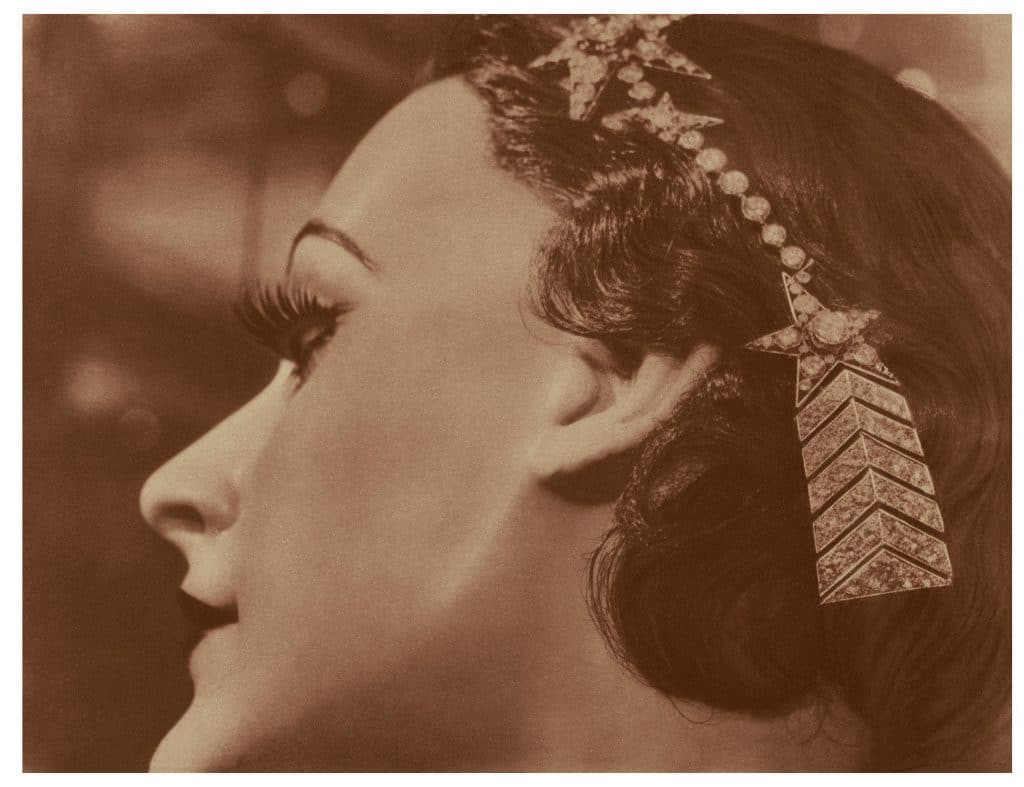

The lyrical and bold Chanel designs centered on five motifs: fringe, ribbons, feathers, the sun and stars. A dramatic diamond fringe headpiece was worn over the brow, while a fringe bracelet draped down the palm. A ribbon was tied in a bow at the front of a necklace and the top of a headband. These textile motifs linked the collection to the couturier’s clothes.

An oversize feather brooch, which could be worn over the shoulder or as a headpiece, represented the freedom of birds. One almost four-inch-wide sunburst brooch featured a large yellow diamond in the center. According to the journalist from Women’s Wear Daily who attended the 1932 press event, it was a tribute to the luxe decor of the Sun King, Louis XIV, and echoed a crystal sunburst clock on display in Chanel’s apartment.

A constellation mosaic on the floor of the orphanage where Chanel grew up was one of the inspirations for the stars in the collection. The most dazzling among them was the Comète necklace, consisting of a star with a long diamond tail that wrapped partway around the wearer’s neck, remaining open at the front.

“With the exception of one ring and one brooch made of yellow gold, the collection’s forty-seven monochromatic pieces were made of platinum and diamonds,” notes Fabienne Reybaud in her book Chanel Jewelry and Watches, part of a three-volume set about the house released by Assouline in December. Reybaud also points out that the jewels were designed to fit a woman’s body comfortably and be worn in different ways, practicalities Chanel was sensitive to as a dressmaker and a woman herself.

Rave reviews flowed in from the members of the press who attended the collection’s single showing. The journalist for L’Officiel wrote, “The exhibition of jewels now being held by Mlle Gabrielle Chanel at her home in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré is one of the most remarkable artistic manifestations in a city so noted for its artistic achievements.”

Nonetheless, the International Diamond Corporation ultimately caved to the demands of the men in the French jewelry industry. The pieces were broken up after the exhibition, and a planned London showing was canceled.

As steely as Chanel was, she was clearly bruised by the experience. She never designed another diamond jewelry collection. Instead, she focused on costume and the demi-fine pieces she made in collaboration with Fulco di Verdura, when he worked at Chanel during the 1930s.

In 1993, the House of Chanel revived its fine jewelry business. Over the years, it has made near-exact renditions of the 1932 designs and imagined new silhouettes incorporating the original five motifs, as well as other themes beloved by Chanel, such as the lion, representing her Leo zodiac sign, and camellia flowers. Notes Eric Naor, owner of Eric Originals and Antiques LTD, which specializes in signed jewels, “The jewelry has been perpetually popular with clients since it was launched because it is so beautifully made and people know the name Chanel.”

It has also been perpetually popular with celebrities. One of the first high-profile moments for the resurrected line occurred at the 1997 Oscars, when Celine Dion wore a reproduction of the 1932 Comète necklace, along with newly designed star stud earrings. More recently, at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, Tilda Swinton sported a feather brooch based on one of the 1932 designs. At the 2021 Golden Globes, Andra Day, Margot Robbie and Unorthodox star Shira Haas all sparkled in Chanel diamonds.

Clearly, the men of the French jewelry industry were wrong when they said Chanel couldn’t create beautiful fine jewelry, but they were right that she would have been competition. Few if any fine-jewelry collections have withstood the test of time like the one designed by Coco Chanel.