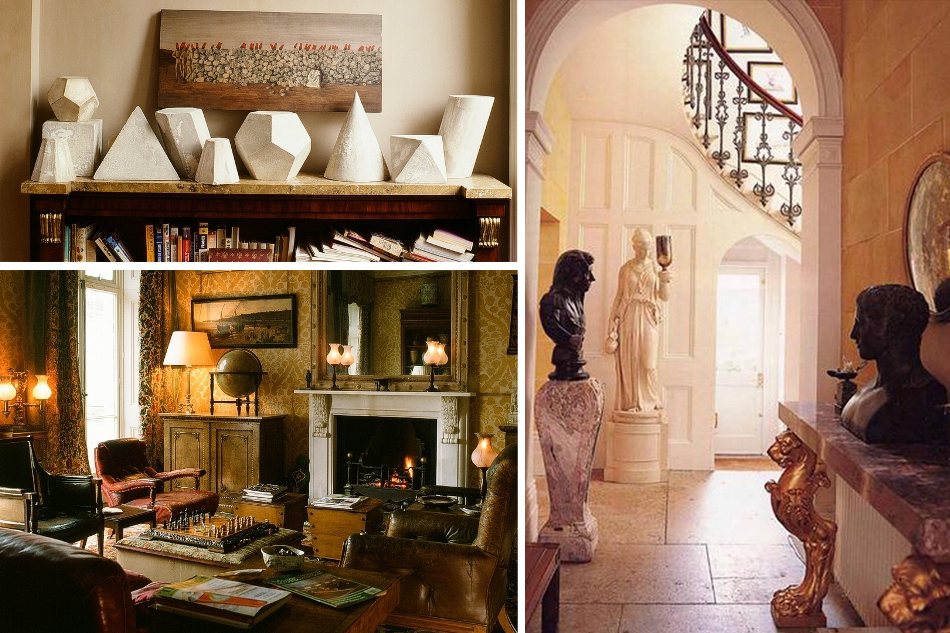

Whether Christopher Hodsoll is in London or L.A. — where he’s photographed in Kathryn M. Ireland’s new studio/showroom that showcases his antiques — he can often be found in a white shirt, navy blazer and khaki shorts (photo by Samuel C. Frost). Top: Hodsoll designed the rooms of this house-like tent for Prince Philip’s 70th birthday party in 1991 (photo by Peter Hodsoll).

September 17, 2014Although he has sold centuries-old treasures to Paul Simon and Paul Smith, Steve Martin and Sting and created sumptuous rooms for royals (Prince Philip; Princess Firyal of Jordan) and celebrities (Mick Jagger), the London antiques dealer and interior designer Christopher Hodsoll lives a bit more humbly. “I have a row house near Portobello Road in the poor part of Notting Hill,” he says, smiling. “I still haven’t found time to finish it.”

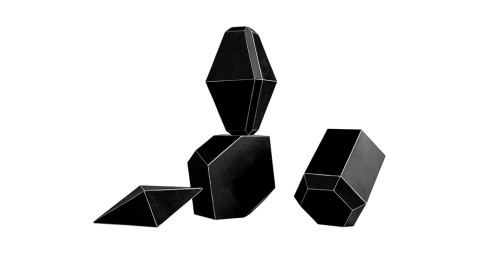

Pity him not. The designer, a co-founder with Lulu Lytle of Soane, the highly regarded classicist furniture collection, has been somewhat pre-occupied. Having recently established a beachhead in the U.S., Hodsoll, already beloved by Los Angeles designers Michael S. Smith, Rose Tarlow and Martyn Lawrence Bullard, has outfitted fellow Brit Kathryn M. Ireland’s new L.A. studio and showroom with some of his treasures: 1720s Venetian giltwood chandeliers, 1840s Scottish and Irish cabinets, a 28-foot-long 19th-century Sultanabad carpet and chairs from La Mamounia hotel in Morocco. “We met years ago working on Lorne Michaels’s apartment in New York,” says Ireland of the joint venture. “We were both dramatic Leos and rather frightened of each other but have come to be longstanding friends. And it’s great to share a space with the most knowledgeable antiques dealer there is.”

While setting up shop with Ireland, Hodsoll rented a furnished, suitably storybook, early-20th-century cottage in Santa Monica, to which the 60-year-old father of four made only a few decorative adjustments. He had a shelf of personal books and DVDs, a pair of vivid watercolors by his visiting daughter and a small collection of dried cactus spines. “I’ve always been attracted to unusual things,” says the dyed-in-the-wool Englishman, who favors a white shirt and navy linen blazer (albeit with khaki shorts) even on the warmest California days. “Even when I was young, I’d scurry around antique shops, buying strange objects of natural history and old minerals in Victorian cases.”

In a 2004 project in Notting Hill, Hodsoll paired an Indian chest of drawers from 1750 with the painting Turkish Pilgrims En Route to Mecca by 18th-century Italian painter Francesco Zuccarelli. Photo by James Mortimer

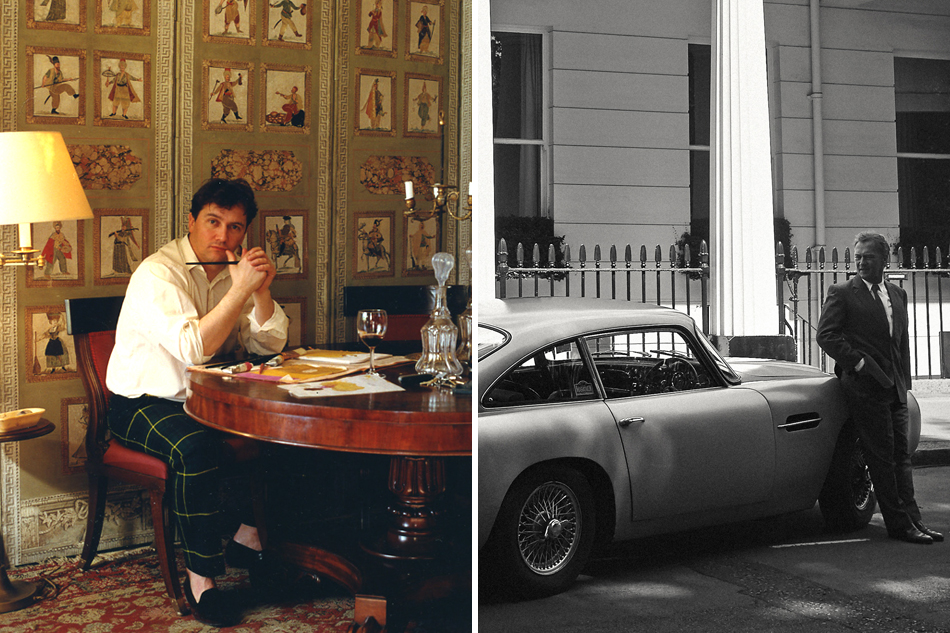

Hodsoll grew up in a rambling 17th-century brick-and-timber manor house in Sussex with a pub on the side of it, which his father ran after retiring from advertising. “He came from an ancient Kent family that went broke in 1803,” he recalls, chuckling. “There were antiques, but that was because old family furniture was much cheaper than buying something new.” Young Christopher studied liberal arts at an English public school, but he was far more interested in playing chess and racing Mini Coopers. When his parents divorced, he moved to London, and, at 17, he began working for a Mayfair dealer, researching antiquities, Renaissance artworks and early European antiques that were sold to old-money clients and institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York.

It was quite a lonely job,” he remembers. “A five-year monkish education in a solitary university.” Hodsoll then ran a gallery for “a rather eccentric” dealer named Peter Twining. “It was a very rough, beaten-up shop in Notting Hill, and he was the most impossible man with customers, but he was my tutor,” he recalls. “He taught me how to understand scale and that things didn’t have to be immaculate.” His next mentor was the antiques dealer, interior decorator and fabric designer Geoffrey Bennison, who created lavish residences for jetsetters like Guy and David de Rothschild in the mid-1970s. “They lived in such a grand style,” says Hodsoll, who sourced accessories for Bennison’s clients, “and he was obsessed with getting everything just right.”

“I see the funny side of ostentation,” Hodsoll explains. “Whenever i bought something that made me smile, it sold immediately.”

In Edmond Safra’s office from Hodsoll’s 1985 Berkeley Square bank project, silk Fortuny curtains and a 16th-century Flemish tapestry help create a sophisticated aura that’s rare for a workplace. Photo by Peter Hodsoll

Hodsoll left Bennison in 1982 and opened a small shop on Pimlico Road, London’s famed antiques destination. When Bennison died in 1984, he left Hodsoll with partial ownership of his successful shop nearby and Hodsoll eventually expanded to five storefronts, attracting an international crowd besotted with the English look. “It was the time when there were only twenty or thirty billionaires in the world,” he notes, “and everyone was trying to outdo one another.” Along with Italian Baroque furniture, he specialized in quirky pieces. “I see the funny side of ostentation,” explains the owner of a vintage Aston Martin that prompts onlookers to make James Bond jokes. “Whenever I bought something that made me smile, it sold immediately. Bill Blass would come in the shop, see something and burst out laughing and then ten minutes later he’d buy it.”

Hodsoll’s discerning eye led to interiors commissions. “I’d been window dressing for so long,” he says. “We’d do tableaux of dining rooms, sitting rooms and studies. I had years of practice, so I could do them pretty quickly.” He designed residences and London offices for the late international banker Edmond Safra and advertising mogul Charles Saatchi. “He’s fabulous, but the most impatient person I’ve ever met,” Hodsoll chuckles. “I did a vast apartment for him in Eaton Square and he was having the ceiling plastered at the same time as the carpet was being laid.” In 1991, Hodsoll decorated a party space for Prince Philip’s 70th birthday in the garden of Windsor Castle. “It was a stately home in a tent. That was the height of my extravagance,” he demurs. “I do love that over-the-top outrageousness, but who would do that today? I can see why the French nobility had their heads chopped off; they pushed it too far.”

Now, Hodsoll strives to creates a timeless, yet livable look, rich with Old World materials, luxurious Continental fabrics and antiques, plus his favorite colors — British racing green, saffron yellow, pale aqua, Wedgwood blue and what he calls “dry, dusty pink.” “Bedrooms should be as empty as possible,” maintains the designer, who admires the work of Peter Marino, Thierry Despont, Bunny Williams and, of course, Kathryn Ireland. And Sir John Soane is such a hero of his that he named his furniture collection after the English neo-classicist architect.

Hodsoll sits at a monumental desk in the office of fellow designer Kathryn M. Ireland’s new L.A. studio, which he helped design. Photo by Samuel C. Frost

“I don’t mind a dramatic living room for guests,” Hodsoll continues, “and a dining room should be slightly theatrical, because you are not going to spend that long in it.” He is quite happy to mix periods and materials, furnishing a conservatory room in London with a Louis XVI–style bergère by Syrie Maugham, a Bloomsbury Group solid-bronze console with horse legs and a 1940s table that appears to be draped and skirted but is made entirely from wicker.

In the 21st century, the antiques market has evolved, Hodsoll says. “After 9/11, tastes changed,” he observes. “Minimalism became fashionable, and clients started going to auctions. Business was going downhill, but 1stdibs was one of the few saviors.” As a result, his enterprise has become more mobile, and he has used his expertise as an antiques dealer to build upon his profile as a global interior designer.

“I just did a job with a lot of fabulous chintz in Australia, a New York apartment with a white lacquer-and-nickel table based on a nineteen-thirties yacht and a modern loft in Chicago,” he explains. “And I recently finished a house in Virginia that is thirty-thousand square feet on one floor — so enormous that you practically have to cycle from one end to the other.”

No matter the size of the commission, or the taste of the client, Hodsoll’s design process is rooted in his own non-traditional traditionalism. “When I walk into houses, my first reaction is panic,” he says, laughing. “I pad around for ages, thinking, What the hell am I going to do here? I like to lurk for as long as possible and think about the practicalities of how people want to live. But even when I do contemporary homes, the emphasis is on luxury and quality.”