April 7, 2019Trattie Davies and Jonathan Toews, of Davies Toews Architecture, designed the new 1stdibs Gallery (where they are pictured), a 45,000-square-foot space in West Chelsea showcasing furniture, art and objects from 50 international dealers (portrait by Emily Andrews). Top: The living room of an airy Fifth Avenue apartment the pair designed contains a Vladimir Kagan sofa and a Frank Gehry chaise longue (photo by Maya Alexander).

Trattie Davies and Jonathan Toews don’t take themselves too seriously. Their office isn’t in a high-rise office building in midtown Manhattan but in a storefront space in the East Village. And its light fixtures were made by the couple together with their 10-year-old son, Jack, using construction paper. But they’re also Yale-trained architects who have collaborated with Frank Gehry (and with whom Davies regularly teaches at Yale).

Since founding their firm, Davies Toews Architecture, in 2009, they have taken on some large institutional projects, such as a 72,000-square-foot Chicago charter school whose facade mixes light and dark bricks in Op-art-inspired patterns. And they have handled dozens of renovations, often making on-site decisions about what to save and what to discard, a process Davies calls “creative demolition.”

When 1stdibs was looking to convert a raw industrial space in a historic West Chelsea building into the first permanent 1stdibs Gallery, with room for 50 exhibitors, it turned to Davies and Toews for their ingenuity and design chops. The goal was to give each dealer a space that felt enclosed, but not too enclosed. Among the models the architects looked at were formal French gardens, where hedges serve as dividers, and the period rooms at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where divergent decorative styles coexist inches apart.

Although the West Chelsea space sprawls over more than an acre, it presented one constraint after another, including level changes and several immovable walls with narrow thresholds. Davies insists, however, that “we wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.” The couple obscured some features and preserved others, at one point even exaggerating the width of a stairway for effect. Those changes were subtle but self-assured. They also designed benches and platforms, in simple geometric shapes that read almost as sculptures.

The Fifth Avenue home, completed with the couple’s former partner, Frederick Tang, features Frank Gehry chairs surrounding the dining table. Most of the walls are painted white, which, Davies says, is “beautiful because you can see light and shadow.” Photo by David Land

Davies and Toews drew on their experience renovating a townhouse in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, that had been chopped up into four apartments. In turning it back into a single-family home, they created a beautiful central staircase whose railing is a sinuous ribbon of plaster. The pair based the stair’s design on details they found during the demolition process, including rounded coffin turns (niches said to make it easier to get caskets down winding stairways). The curves play out differently on different floors, depending on the room layouts, and culminate in a softly shaped circular skylight.

A powder room in the home required careful choices. With a pocket door that is often left ajar, it is visible to anyone in the kitchen, so “we wanted it to be beautiful,” Davies says. They gave that room a Fornasetti wallpaper whose clouds, seen through the door, seem to blend in a marbleized blur with the Calacatta turquoise stone of the kitchen backsplash.

Left: Davies Toews was tasked with restoring a four-apartment Cobble Hill townhouse to its original single-family configuration. Right: A half bathroom off the kitchen is visible whenever the pocket door is open, so they outfitted it with Fornasetti wallpaper that complements the Calacatta turquoise stone in the kitchen. Photos by Maya Alexander

The pair created a stair similar to the Cobble Hill one in a Fifth Avenue apartment, where the curves, Toews says, resulted from the need to plaster around structural encumbrances. New York flats often have inexplicable framing systems — “bananas beams,” Davies calls them, noting, “We used to be upset when we found an extra column. Now, we like seeing what we can let out or let loose, rather than trying for perfection.”

In enlarging the apartment’s living room, the couple removed a wall but couldn’t take down the columns it contained. So they created a colonnade and, behind it, a reading niche, which is clearly defined but open to the main living area. The result is a layering of spaces, with interior foreground, middle-ground and background vistas, something Davies and Toews try to achieve in every project.

Nearly all the home’s walls were painted white, but not because of a lack of imagination. “I think white is beautiful because you can see light and shadow,” Davies says.

In this case, the white hue responds to the light conditions and the colors of the trees in Central Park, whose tops appear practically outside the apartment’s oversized windows: Sometimes the walls are white, but sometimes they’re green, Toews notes, sometimes yellow, sometimes pink.

Davies and Toews helped friends combine two apartments on the Lower East Side and created a “reading cube” in its living room for the family’s two daughters. The custom millwork is by N.E. Perrin. Photo by Maya Alexander

The Fifth Avenue apartment, furnished with fine art and antiques (and a stunning corrugated cardboard chaise by Gehry), was a high-budget job. But Davies and Toews have done far less expensive renovations. On the Lower East Side, for instance, they helped friends combine two affordable units. After knocking down walls, they patched the parquet floors, but imperfectly, so you can still see the old layout, almost archaeologically. They designed a kitchen using Ikea cabinets, Heath tiles and plywood. And they used plywood to build the home’s most distinctive feature: a “reading cube” for the book-besotted family. The eight-cubic-foot space has round openings that let in light and air and the family’s two daughters.

Left: The designers outfitted the Lower East Side apartment’s kitchen with Ikea cabinets, Heath Ceramics tiles and plywood shelves. Right: The family of avid readers needed plenty of shelving for their books. Photo by Maya Alexander

The pair operated on a larger scale in turning part of the basement and subbasement of New York’s Plaza Hotel into a gym called La Palestra. A collaboration with Gehry, the project involved incorporating massive ducts and huge steel columns. In this setting, requiring grand gestures, they created pyramidal recesses in the ceiling that read both as skylights and as complements to the column’s flared bases.

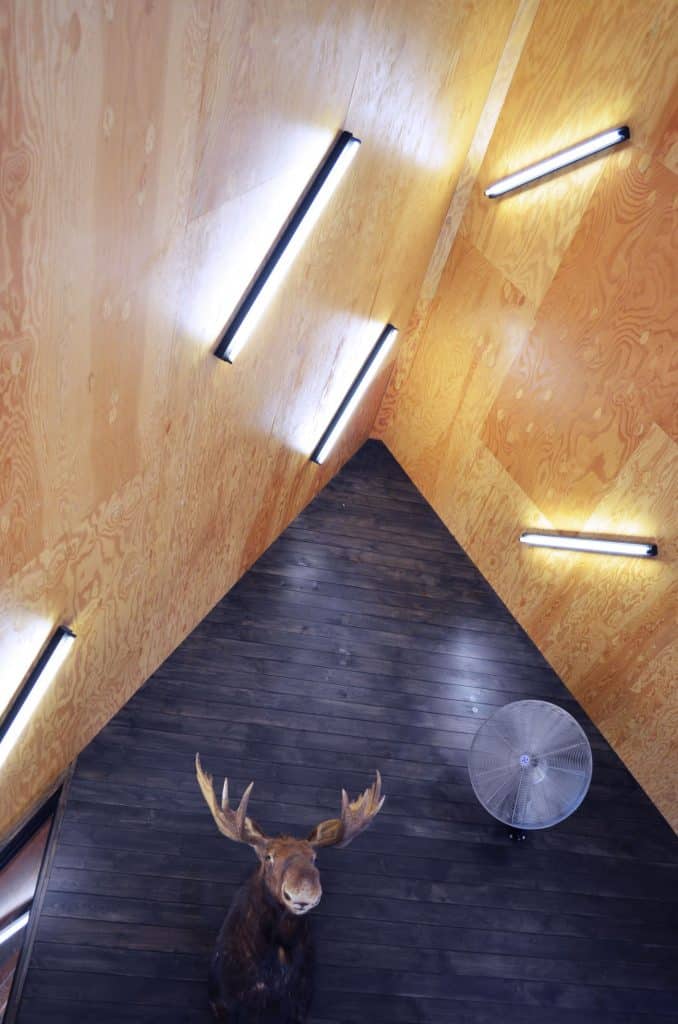

Davies Toews’s range is wide. The not-for-profit PARC Foundation brought them in to design several small buildings in an old campground it is restoring in northwestern Maine. The newest such structure contains a general store and a manager’s apartment. Given a strict budget and stricter schedule, the couple decided to build an A-frame, but to make it unlike any other A-frame in the world. The outside is made of corrugated fiberglass over “building felt,” creating a fuzzy, otherworldly quality. Inside, the architects installed fluorescent lights with black-painted housings that turn them into bold punctuation marks on the angled ceilings.

Davies and Toews converted a raw industrial space in a historic West Chelsea building into the 1stdibs Gallery. The goal was to accommodate 50 exhibitors, giving each a space that felt enclosed, but not too enclosed. Among the models they drew on were formal French gardens and the period rooms at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On the right is the installation The Line of Beauty by The Archers, which features portrait busts and pedestals from the 17th to 21st centuries. Photo by Maya Alexander

Now, they are working in a far more urban setting, turning an old factory building in Ridgewood, Queens, into an arts center.

With projects ranging from apartments to galleries to school buildings to gyms, the firm has yet to specialize. “It might hurt us at some interviews,” says Toews, meaning there are advantages to having a particular area of expertise. “But we also hope it’s a strength. For us, each project is about seeing things with new eyes.”