June 11, 2023First, there is Hadspen House, a beautifully restored, classically proportioned Georgian mansion of honey-colored stone. A half a mile away is the Farmyard, a former dairy farm whose buildings are now occupied by guest suites.

Scattered across 800 acres of exquisitely planned and designed gardens and woodland are not just these accommodations but also restaurants, cafés, a spa and sumptuous indoor and outdoor swimming pools. And, in addition to these: a Roman villa, a bee sanctuary, a vegetable garden, a butchery, a bakery, a food shop, a croquet lawn and a cider press fed by the hundreds of apple trees on the estate.

This is the Newt in Somerset, an idyllic, English country estate that is both contemporary and rustic, extraordinarily ambitious and utterly laid-back. But when its South African owners, Karen Roos and Koos Bekker, bought the property, in 2013, the couple had no plans for anything other than an English country home. “It’s all Koos’s fault,” Roos says with a laugh. “He thinks big.”

Roos, a former editor of Elle Decoration South Africa, and Bekker, the chairman of the Naspers technology and publishing group, had already created the extraordinary, similarly expansive Babylonstoren, the impossibly gorgeous estate in the Winelands, outside Cape Town. That multipurpose (winemaking, rice-growing, honey-producing, scent-fabricating) site is a magnet for design obsessives, foodies and gardeners worldwide. “The Versailles of vegetable gardens,” wrote a reviewer in Britain’s Sunday Times.

At Elle Decoration, Roos “established a new aesthetic that reinterpreted South African design through a contemporary prism,” says Aspasia Karas, the former editor in chief of Marie Claire South Africa. “She gave old tropes a makeover.” Roos brought the same skills to Babylonstoren and the Newt, creating a distinctive look by combining a pared-down, Scandinavian simplicity (whitewashed beams, chalky walls, fine linens) with unobtrusive luxury and textural contrast. She topped these off with idiosyncratic arrangements combining bold contemporary pieces from Tom Dixon or Moooi with antiques and quirky objects.

“I come from the point of view of someone who always had to think about the photographs,” she says, referring to her editorial eye. “I am always looking at the composition of a space and — most crucial! — the lighting.”

The couple discovered the Somerset property as part of a broader search. “Koos was thinking about food for the future, a sustainable farming project,” Roos explains over lunch at the London offices of architect Richard Parr, who designed the Farmyard. “We looked at a few places around the world, and I thought, ‘I would like to be in the English countryside.’ ”

That desire sprang from reading English literature, particularly the novels of Jane Austen. “And the school stories of Enid Blyton,” says Roos, who was born and raised in Pretoria, South Africa, and also cites another, less literary influence. “In my head, I grew up in the Sixties in London! My sister and I would draw all the Carnaby Street clothes and try to make them.”

After spotting an advertisement for Hadspen House in Country Life magazine, Roos and Bekker went to see it. “We walked in, and that was it,” Roos says. “We loved this southwest part of England immediately, and we loved the scale of the house. But we didn’t think about a hotel at that point.”

The house and estate, situated about a two-hour drive southwest of London, had been occupied by members of the Hobhouse family for 230 years, most recently by the famous garden designer and writer Penelope Hobhouse. But as with many large estates, the costs of maintaining the house and the land were challenging.

“The house had been divided badly, some other properties rented out, and a lot of the beauty had been lost,” Roos says, explaining that the gardens, including ones designed by Hobhouse, had been flattened. Adds Parr, “Where the Farmyard is now, there was a modest farmhouse and an amazing collection of buildings, but many on the point of deteriorating. When I met Karen and Koos, around 2017, they were still sort of camping in the main house.”

After living in the house on and off for around two years, Roos and Bekker started to consider turning it into a hotel. “Unless you have a very big life, with lots of parties, you aren’t really sharing it,” Roos says. “It made sense that it be lived in up to its capacity.”

They called in the landscape architect Patrice Taravella, who designed the Babylonstoren gardens, and began to work with the Bath-based architect SIMON MORRAY-JONES on restoring the house. The idea was to emphasize the period detailing while opening up the partitioned areas to create airy and handsome living spaces that look out on the sweeping lawns and garden.

The Newt opened in 2019. (The name came from a year-long delay occasioned by the discovery on the property of great crested newts, a protected species of salamander that had to be carefully relocated.) But well before then, Roos and Bekker were thinking about the dairy farm buildings half a mile away from the main house. Or at least Bekker was.

“I say no to everything,” Roos says. “And it was all these different buildings, impossible to imagine how to make it into a hotel. We needed a very smart architect.”

Enter Parr, who had experience with converting barns and historic buildings but had never designed a hotel. In fact, it wasn’t clear that it would be a hotel, Parr says. “I went away without a brief.”

“That sounds like us!” Roos adds. “We just knew we were going to do something.”

That something is now the Farmyard at the Newt, comprising nine existing farm buildings, set in formal gardens, that have been converted to contain 17 hotel suites, along with a spacious restaurant, a sumptuous indoor pool and spa and a bar and lounge that provides an inviting spot for guests to gather.

“There was a threshing barn, a cheese-making barn, stables, a granary and more,” Parr says. “Many had become obsolete as farming changed. Some walls were derelict, there was rusting metal, chains hanging, and at first, you couldn’t work out what was what. But I went away buzzing at the beautiful setting and the possibilities.”

The project soon defined itself as an extension of the existing hotel. The original Newt at Hadspen House, Roos says, “is like a gentleman’s country estate, and the Farmyard is more casual. You are surrounded by farmland and can see the farmer bringing in his sheep. It depends on what you want as a guest.”

The Farmyard is also more contemporary in its design, while remaining every bit as stylish and luxurious as Hadspen House. For the suites that he created in the outbuildings, Parr took his cue from the original function and character of each space and stuck to local materials: golden Hadspen stone, Blue Lias stone and Forest Marble limestone, mostly from a quarry just a mile away.

“We could have made many more smaller rooms or fewer huge ones,” he says. “But we simply tried to use each building to its maximum potential, creating the right views, the right light. Each one has something of interest: the original flagstone floors, incredible beams overhead, amazing views over fields, a bread oven, a dark atmospheric space.”

Parr also added two new structures to the property: a horseshoe-shaped buggy shelter near the entrance to the Farmyard and a building containing two suites. In addition, he created a contemporary version of an English barn to house the swimming pool, with one side composed of a huge sheet of glass that brings the outside in.

“The idea behind the Farmyard was to reimagine a use for traditional buildings, and a barn is a big gathering space,” Parr says. “We decided it would be wonderful to swim in a barn, with light streaming in and flickering on the beautiful blue of the pool.”

It was important to everyone not to create a pastiche. “The structure is a really crisp, zen-like building with a really contemporary feel,” Parr explains. “But then, Karen will throw in an eighteenth-century engraving and blow it up to cover an entire wall.”

At the center of the Farmyard is the Garner Bar, a communal honesty bar, library and games room created in a derelict storage building. A tall circular brick chimney holds a crackling fire, alluding to both a forge and a bakery, “where people gathered and worked,” Roos says. “A lot of all this for me was to do with farming: Thomas Hardy, George Elliot, Austen. It was important to me that there was a heart in the middle of the buildings where you feel at the center of the community.”

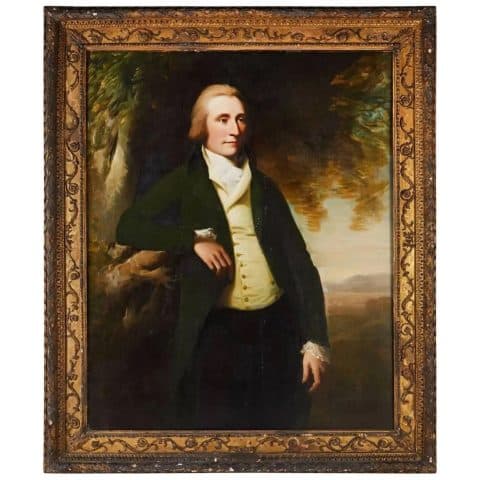

Despite the scale of the project, Roos took on responsibility for all the interiors. “I’m a bit of a dictator about what it will look like and where there will be a painting,” she says, noting that many of the late-18th-century and 19th-century portraits that adorn the bedrooms were sourced through 1stDibs. Parr designed much of the furniture, including the metal bar in the games room. Bekker’s favorite thing, Roos says, is to choose the books for every room.

“Karen is very good at trawling design fairs, and often she will find a contemporary reinterpretation of what might have been there at the time the buildings were constructed,” Parr says, pointing to the updated version of a roll-top bathtub in one of the rooms and a modern Magis rocking horse that references an old-fashioned child’s toy.

The gardens were designed with equal care, with a stream running through the formal lawns into a large pond that reflects the huge willow drooping over it.

“Even the way the water flows is carefully thought about acoustically and visually,” Parr says. “There is a step cascade, a still water trough, a curved rill, a ripple over steps and a final waterfall. It’s a contemporary version of a natural stream that might have run over sticks or logs, and it’s very musical.” Each area of the property, he adds, “has as many dimensions of enjoyment as possible.”

The ultimate goal was for everything to have a purpose and provide pleasure. “There must be no white elephants,” Roos says. “Everything should be used and every place feel good to be in.”