March 28, 2021Asked to describe her style as an interior designer, Heide Hendricks pauses, then says, “I do houses where you’d want to spend a pandemic.” In fact, she says, during the past year, “I’ve had many clients reach out to me and say, ‘Thank you, because we’re completely comfortable, and we feel so fortunate to have this home right now.’ That means the world to me, because it’s my art.”

Hendricks, the principal interior designer of the firm Hendricks Churchill, has become known for a kind of house that a grandma or a hipster (or a hipster grandma) would feel comfortable inhabiting 24-7. Always on the hunt for vintage and antique pieces, she finds distinctive objects that may not “match” but somehow bring out the best in each other.

She arranges these items in groupings that appear to have developed over time. “It never looks like the designer was just there,” she says. And she doesn’t crowd items together. “I try to find the harmony, but I don’t like clutter. I still want things to breathe. I want you to appreciate them and experience them individually.”

For years, Hendricks was a publicist in Manhattan. But she and her husband, Rafe Churchill, renovated houses at night and on weekends. Starting in Williamsburg and then moving up to northwest Connecticut’s Litchfield County — where the couple is now based — they completed eight flips, with Hendricks’s interiors often helping the bottom line. (Some of the houses were sold fully furnished.)

Churchill built new houses, too, including one for the cookbook author Jessie Sheehan and her husband, Matt, also in Litchfield County. While that house — its unadorned facades reflecting the Sheehans’ love of Shaker architecture — was underway, the clients lived in an Airstream trailer on the site, and on very cold days, Hendricks would invite them over to her home nearby. They came to love Hendricks’s style — and eventually hired her to do the interiors of what she came to call “the New Farmhouse.”

Hendricks kept things spare; if she got too fussy, the clients would remind her of “our Shaker friends.” Indeed, avoiding anything extraneous, she decorated mainly with color, including the hues of the wildflowers that line the driveway to the house. “I think of color as a kind of furnishing,” she says.

On the ground floor, the only window treatments are the Farrow & Ball colors she applied to the windows’ trim. Those colors vary widely. On the other hand, all the sashes and muntins are painted dark blue. “I find if you have a dark-painted sash and muntins, they disappear as you look out to see the view. It’s one of our signature devices.”

The house itself is very green, and not in the Farrow & Ball way. It was designed with solar and geothermal systems. So, when it came to furnishings, Hendricks wanted to do her part for the environment. “I sourced a lot of vintage or antique pieces,” she says.

Among them are the brass floor lamps in the living room and the iron daybeds on the front porch, bought from Berkshire Home and Antiques. “And if we did have to use, for instance, a new sofa, we made sure it was free of toxic chemicals,” she adds.

By the time she was finished with the New Farmhouse, Hendricks considered herself an interior designer. “It was a labor of love that launched my career,” she says. Opening an office in the Litchfield County town of Sharon (and another in New York), she “hit the ground running,” creating houses so cozy and comfortable that clients sometimes tell her, when she turns over the keys, “It feels like we’ve already been living here.”

Four years ago, she merged with her husband’s design-build firm to form Hendricks Churchill, although, she recalls, “everyone thought we had been partners for years.”

Hendricks and Churchill live with their kids and their wheaten terrier, Daisy, in a late-18th-century farmhouse on 33 acres (the remnant of what had once been a 1,500-acre dairy farm). They had been admiring the house for the 15 years it was on and off the market, watching as the price dropped, incredibly, from $2.4 million to $775,000 in 2018. That’s when they made their move.

The building is a mash-up of architectural styles dating from the 1760s to the 1920s. Some rooms had fine period details; others had no details at all.

“The day we closed on the house, we walked through it room by room and made a list of what we were going to do,” Hendricks says. “Astonishingly, it didn’t change.”

That list included everything from removing extra doors (the result of 200 years of ad hoc additions) to installing crown moldings, for “stylistic consistency with the Greek Revival window trim and the tall baseboards,” Hendricks says. To create a double-height sunroom, she and Churchill removed some old chestnut wood from the loft of a small barn attached to the house, repurposing the lumber as the handsome floor of the front entry.

Hendricks used wallpaper in many of the rooms, including an abstracted pine tree design by Fayce Textiles in the living room, block-printed local fauna by Mark Hearld in the dining room and Marthe Armitage’s chestnut leaves in the powder room. “The patterns we selected were playful nods to the views outside,” says Hendricks.

Then, she began mixing new, vintage and antique furniture. In the dining room, she hung a new brass fixture from Lambert et Fils over a custom tiger-maple table surrounded by Børge Mogensen chairs.

The ceiling fixture in the living room is a David Weeks Cross Cable chandelier. One of Hendricks’s rules is that, if a piece is contemporary, it should look contemporary. (She doesn’t like new pieces that try to appear old.) By the same token, she vows, “You’ll never see a faux finish in any of my projects. Authentic is very important to me.”

She uses her own house as a kind of laboratory for her ideas. And though it’s never quite done, she says, “ I feel like, because of Covid, we really broke it in as a family home.”

Hendricks grew up in Western Connecticut, where both of her parents were artists. She moved to New York after studying art history at Syracuse University and, despite relocating back to her home state in 2003, hasn’t left the city entirely. Many of her projects are apartments there, including a charming Greenwich Village flat for a repeat client.

“The homeowner already trusted me, and I knew that she wanted a soft palette, almost monochromatic,” say Hendricks. Her paint selections start out dark — the entryway is painted Farrow & Ball’s deep gray Mole’s Breath — and get lighter and lighter as one moves through the apartment. That way, it feels as if the space is opening up to you, she explains. The kitchen in the back is bright and airy.

Hendricks also knew that the client was ready to invest in a few important pieces of furniture. She looked for them on 1stDibs, in one case simply entering search terms like “highback,” “leather,” and “armchair.”

“It’s amazing that you can just describe what you want in plain English and get this whole selection,” she says. That particular search led her to a 1960s lounge chair in the original leather by Norwegian designer H. W. Klein, which she purchased from MORENTZ and placed near the living room fireplace.

Photo by Chris Mottalini

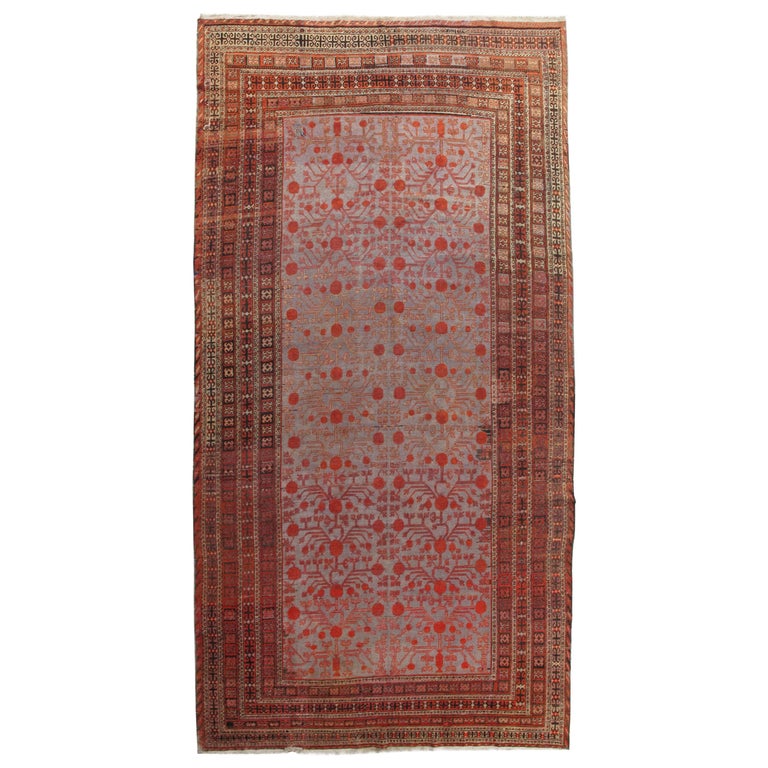

The chair, she says, “helped the whole room come together.” An antique Turkish Berber rug picks up on the red leather, as does a B&B Italia sectional sofa covered in a Zak+Fox fabric. Next to the chair is a dark-blue lacquered library table she designed herself. An Apparatus chandelier hangs above a BDDW dining table next to a Mogensen sideboard from 50/60/70 and a shield-shaped mirror from the Netherlands.

One of the trickiest things for an interior designer is knowing how, and how much, to charge. Hendricks bills by the hour, but potential customers can’t help wondering how many hours their job will entail.

Luckily, Hendricks says, “by now, I’ve figured out that when all is said and done, most jobs work out to about the same amount per square foot. So I tell them that amount. I like to be very transparent. Because the most successful projects are based on a great relationship.”