March 10, 2019Hubert Le Gall’s monumental mirror, Epoca lamp and rabbit gueridon furnish the salon at Saint-Calais, collector Pamela Mullin’s 17th-century home in Normandy. Top: A herd of Le Gall’s Odette l’autruche lamps in patinated bronze illuminates the garden. All photos © Pascaline Noack from Hubert Le Gall, Flammarion 2018

An elegant bronze side table depicting the starry dream world of a sleeping dog, a wingback chair that evokes oversized rabbit ears (with a powder-puff tail to match) and a glass-topped coffee table filled with ball bearings that invites magnetic play — the fantastical creations of French designer Hubert Le Gall marry beauty and whimsy in a way that is so unexpected the results could be confused for hallucinations.

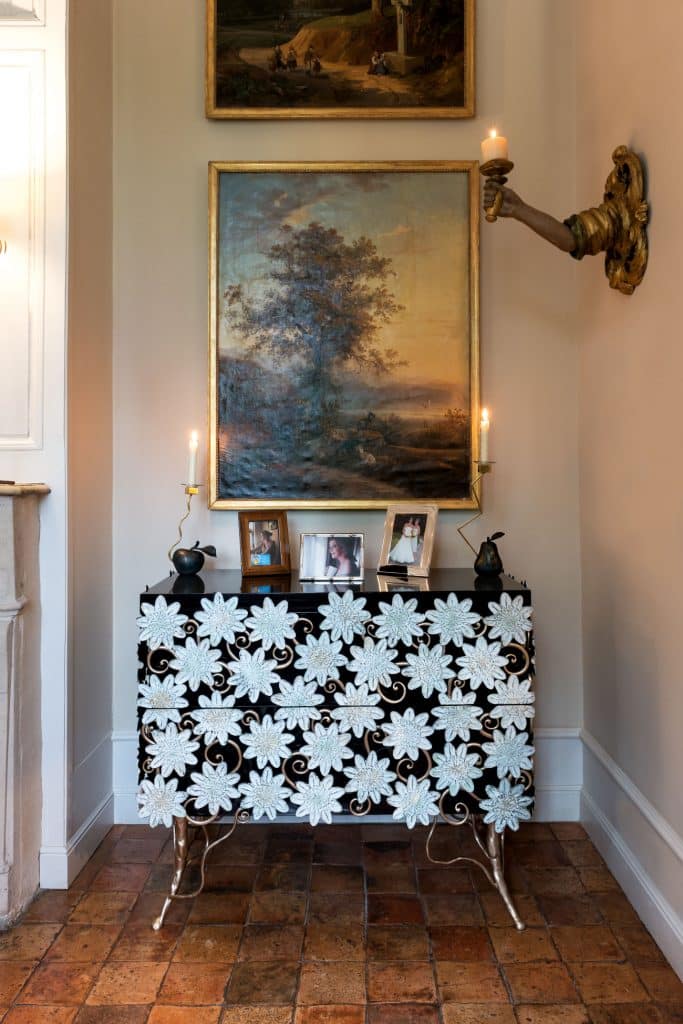

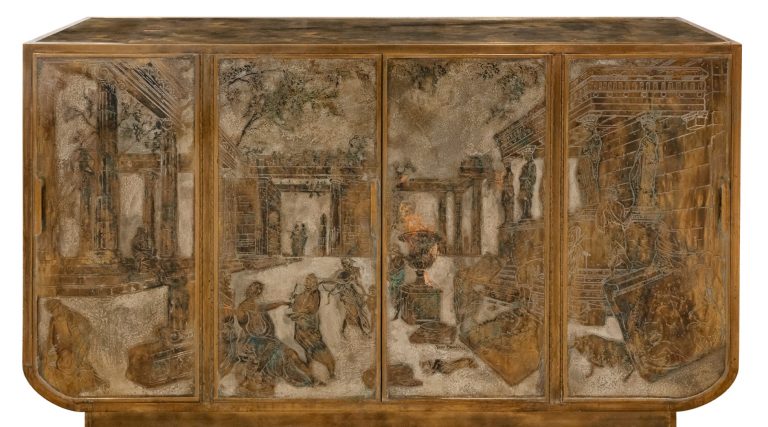

Even more surprising is finding this exuberant work installed throughout a stately 17th-century hunting lodge in Normandy, France, that is otherwise stuffed with 18th-century furniture. At the proud manor of Saint-Calais, owned by the American collector Pamela Mullin, Le Gall’s rabbits sprout from the branch-shaped frame of a monumental mirror above a fireplace, candleholders grow out of bronze pears and apples, and a saw-toting Pinocchio stabilizes a console table with his severed nose.

This unlikely, illuminating mash-up of periods is the result of a multiyear collaboration between Le Gall and Mullin, one of his most ardent supporters, who commissioned the designer to create a large mirror for the lodge. Several other pieces from his collection were chosen for the project, which is featured in the new book Hubert Le Gall: Fabula, published by Flammarion.

Twenty First Gallery, in Manhattan, is hosting an exhibition of the same name through April 15. It is Le Gall’s first retrospective in the United States and, in many ways, the show that gallery founder Renaud Vuaillat has been waiting his whole career to present.

Formerly a Paris-based dealer of 18th-century antiques, Vuaillat credits Le Gall’s work with his decision to shift his focus to contemporary design. Specifically, he cites Pic Poisson, a combination table and floor lamp shaped like a long-necked bird jabbing its beak through the table’s rippling surface to catch fish on the floor. “It was a beautiful piece, very high quality yet playful,” recalls Vuaillat. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh, people are really starting to do exquisite things.’ ” He was reminded of the masterful furniture makers of centuries past. “I decided I had to get into this world,” he says. Vuaillat moved to New York in 2006 and opened Twenty First Gallery two years later. Le Gall was, of course, among the first designers he represented.

Pinocchio and his tell-tale nose are the inspiration for several pieces in the designer’s collection, such as the lamp above. “I thought I was Geppetto, the furniture-maker who created him,” says Le Gall in his new monograph, “but I then realized that I had the wrong character. I was Pinocchio himself.”

Today, Vuaillat continues to see parallels between Le Gall and the French furniture makers who preceded him. He points to the ebony Ferriere cabinet Le Gall designed in 2017, which sits on golden vine-shaped legs and is wrapped by painted bronze flowers. The flowers refer to the work of Andy Warhol, Vuaillat notes, adding, however, that “to me, it’s the contemporary version of the Louis XV chests of drawers that I used to seek.”

Le Gall’s creativity has earned him many other high-profile admirers, including architects and designers like Peter Marino, Jacques Garcia, Brian J. McCarthy and David Scott. “Hubert creates the most exquisitely crafted functional objects,” says Scott. “His elegant menagerie delights with its whimsy and diversity. I’m drawn to its innate happiness.”

According to Le Gall, conjuring that sense of joy is exactly the point. “That’s my personality,” he says. “I’m very sincere in my work and try to make things that reflect me. I try to be happy in life and to make others happy. I don’t think we buy things only for their function. We buy them because there is a story. I work from this idea of the affection we have for the objects surrounding us.”

Mullin’s furry friends settle in on the couch behind Le Gall’s Pica and Pica d’or tables.

Growing up, Le Gall spent his childhood consumed by the act of drawing and initially wanted to study architecture. Discouraged from this pursuit by his father, he studied finance in Paris instead. He earned his diploma but almost immediately gave up the world of money management to try his hand at something more creative. “I just decided to come back to my real nature,” he says. “I wanted to express myself, and painting was the easiest way. I began making a lot of portraits.”

“Between sculpture and furniture, there is just the question of function,” says Le Gall, pictured in his Paris studio.

While delivering those paintings to clients’ homes, he began fielding questions about where they could find artistic furniture. “I was intrigued by this idea of function,” says Le Gall. “I thought of the Arts and Crafts movement at the end of the nineteenth century in England, with William Morris. They mixed furniture with painting and sculpture. Between sculpture and furniture, there is just the question of function.”

To Le Gall, furniture seemed somehow less constraining than sculpture. “I felt even more free to say, ‘No, I’m not an artist — I’m just doing furniture.’ ” In the late 1980s, he partnered with a trained carpenter, established his Paris studio and began sculpting plaster maquettes for pieces like his flower tables, whose horizontal surfaces are formed by individual bronze blossoms supported by stem-like legs. “The furniture I wanted to make was between sculpture and furniture, so I wanted to use bronze, which is a material of sculpture,” he says.

By the early ’90s, he had stopped painting entirely. He began expanding the network of artisans he worked with to produce pieces that now include glass, stone, gold leaf, resin, embroidery and wood. “I think it was good for me not to have been at school for this, because I am really free to do what I feel,” says Le Gall, who continues to plumb his emotions and dreams for inspiration.

Describing the console at Saint-Calais, he says, “The Pinocchio is a portrait of me. In the beginning, I thought I was Geppetto, the carpenter. But I’m not a carpenter. I’m just a liar. A designer is a nice liar who is trying to make your life better. We try to seduce people.”

Shop Hubert Le Gall at Twenty First Gallery on 1stdibs