Originally published August 5, 2018Janinna Caverly (left) and Julie Charbonneau are partners in the quickly growing Toronto firm Julie Charbonneau Design (portrait by Alex Evans). Top: This library of a Toronto home features a custom JCD sofa with a Stella lamp by CTO Lighting on the right; the glass coffee table is by Fiam (photo by Naomi Finlay).

The lament “They don’t make things like they used to” has a special resonance for some interior designers. Julie Charbonneau — principle, along with Janinna Caverly, of Toronto-based Julie Charbonneau Design (JCD) — is unquestionably one of them. Charbonneau finds anything synthetic, precast or prefabricated unacceptable. “It’s about being true,” she says of her design philosophy. “I like natural colors and materials. I like real bronze or linen. I don’t believe in faux finishes. Things should feel alive.”

That devotion to the genuine characterizes the work of her firm, and one senses it — if only subliminally — in every JCD environment. Substance, weight, materiality, authenticity: these qualities have attracted an international roster of clients whom Caverly describes as successful people in business and sports, as well as families of means. JCD works in Canada from coast to coast, but it has also taken on projects in Europe and is now getting others under way in New York and Florida. At any one time, the studio might have between 20 and 30 commissions in the works — impressive for a company that’s been around in its current form for fewer than four years.

The living room of the Toronto home includes an Aldo Tura coffee table, R & Y Augousti bowls and a Porta Romana lamp. Photo by Naomi Finlay

Of course, its roots run deeper than that. Charbonneau’s mother “loved to move furniture around, and I became her design partner,” the Montreal-born designer says. She studied interior architecture and got her start working for a chain of fashion stores, where she headed up design and window display. When that company was sold five years later, she bought and renovated a house in suburban Montreal with the intention of flipping it. “I did everything,” she says, “even the runs to Home Depot. It taught me a lot about how construction works.” One couple who came for a look loved the house but not the neighborhood, so they bought elsewhere and gave Charbonneau her first interior design commission. She established her firm in 2002 and slowly developed a client base.

Charbonneau was introduced to Caverly by a mutual acquaintance in 2014. At the time, she remembers, “I was experiencing all the down sides of working by myself, designing only two hours a week because I had so much administration.” Caverly not only took that off her hands but also arrived toting a fat file of industry contacts. The Toronto-born management pro had already helped build another design business from the ground up, serving as vice president of the 30-person firm before connecting with Charbonneau. The pair joined forces in Toronto in late 2014; since then, JCD has more than doubled in size and currently has more than 15 employees.

A trio of Gabriel Scott Briolette pendants is mounted over the thick marble-topped island in the kitchen of a King City, Ontario, home. The artwork near the window is by James Lahey. Photo by Naomi Finlay

Charbonneau believes the firm’s insistence on quality and customization is an imperative, not a choice. “Every interior is different, and every client is different, so we have to adopt a bespoke approach,” she says. “We try to bring in new materials, new details. We spend a lot of time drawing completely new profiles for a door or finding new spindles for a stair and creating a baseboard that has marble insets.” The level of detail JCD achieves is impressive. The millwork is a tour de force, especially in the more classical projects. In one home, for example, a corridor is lined with baseboards that are a foot wide and stepped with a dozen levels. Above them are recessed panels and, at the hall’s terminus, a mirrored niche framed by elaborate pilasters. Meanwhile, the lintel over the kitchen range has about 20 hand-carved, stepped levels.

Integrity of materials is equally important to the designers. By fuming the oak they employ for parquet de Versailles floors, they bring out the wood’s beautiful figuration. Furniture and cabinetry are made of solid wood rather than of lesser materials masked with expensive veneers. Not only is the door of Charbonneau’s own Montreal loft constructed of solid rosewood but so is the generous paneling that frames it. When stone is used, whether rustic and honed or refined and polished, it is thick and substantial, and contrasting types are often juxtaposed, so that the characteristics of each are heightened. And there’s no bait and switch when it comes to construction components. “A lot of contractors use hollow beams and think you can’t tell the difference. But we can tell the difference!” Caverly says, adding, “Hand-painting the paneling in a library instead of spray-painting it takes double the time and double the money, so we’re very expensive.”

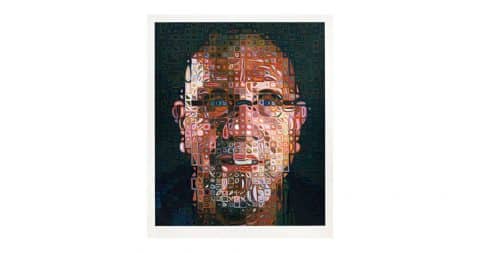

The entry hall of the Toronto home features artwork by Robert Longo, a Lindsey Adelman Branching Bubbles chandelier and a Collection Particulière marble vase. Photo by Naomi Finlay

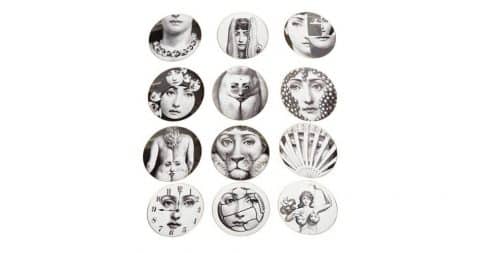

To allow these various elements to shine, the firm keeps its environments uncluttered and uncomplicated. “There should be one focus,” Charbonneau says. “I don’t do well with stuffy.” They are also generally monochromatic. “I like to work with a dark-light contrast,” she adds. Color and pattern show up only as accents. Not surprisingly, considering her firm’s emphasis on craftsmanship and quality materials, Charbonneau loves antiques. “It’s good to have a few signature pieces,” she explains. “It’s about how you put things together.” At the end of the corridor mentioned above, for instance, is a garlanded, gilt and marble-topped French Rococo table. A contemporary loft is graced by a vintage Arne Jacobsen Egg chair.

What can be said about all of JCD’s rooms — even the modern ones — is that they have a classical scale, order and symmetry. This rigor underlines the substantiality of the furnishings and materials, reinforcing the overall impression that these women respect and aspire to old-world design ideals. In other words, a historical orientation lends aesthetic substance to the material substance.

Julie Charbonneau Design is now exploring the possibility of licensing designs for interior door hardware, to be produced by one or more of France’s top manufacturers. But the more immediate plan, Caverly says, is to bring an architect on board, “so we can be fully turnkey.” That will likely make things even busier, at least in the short term. “Maybe I’ll clone myself,” she jokes.

“It would be nice to have more time in the day for both work and life,” Charbonneau adds. “But my past experience in this business? I wouldn’t change that for the world.”