July 23, 2023As befits a master classicist, Thomas Jayne believes that fine design travels well and makes itself at home in any architectural context. The designer had the opportunity to prove his point when a Philadelphia client for whom he had decorated a four-story 1864 townhouse 20 years previously decided to downsize. He engaged Jayne, who has won interior design awards from the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, to reimagine their pedigreed collection of 18th-century European antiques, Asian ceramics and lacquer, as well as 20th-century art and design, in an apartment in a new glass and steel tower. Measuring 4,300 square feet, the flat occupies an entire floor — and it offered a fair share of challenges.

“It has a magnificent view of Independence Hall, and in order not to block other people’s views, the building is triangular,” Jayne explains, with a laugh. “So, trying to make traditional square rooms was folly.”

Purchased as a raw, loft-like space, the apartment needed logic and energy, the designer says. “Our working model is about creating harmony between the old and the new. We had to fit the ancient into this triangle with a big dose of modern.”

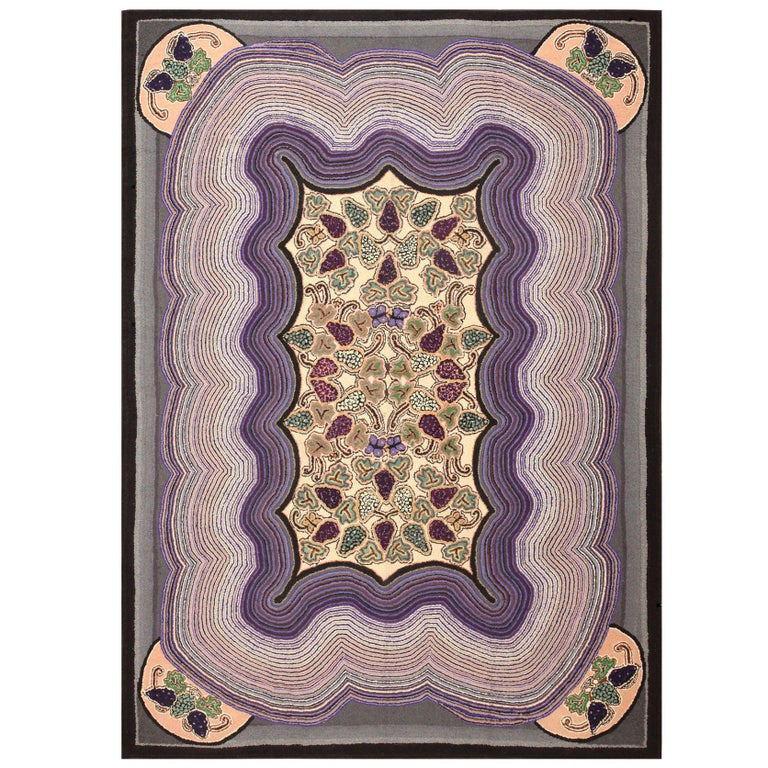

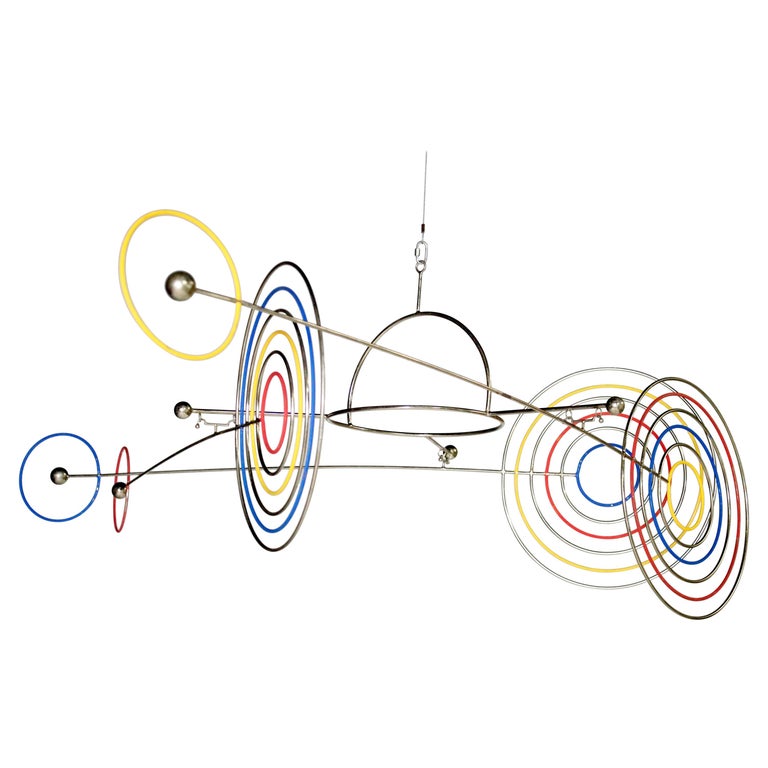

Jayne and the client, a trustee on the European Decorative Arts Committee at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, began from the ground up, laying oak in a Regency-style herringbone pattern with an ebonized border on the concrete floors, painting enormous structural support columns in a soothing shade of cinnabar and adding walls to define spaces. The walls were also key to accommodating an array of artwork, including an 18th-century neoclassical oil, a mid-century Francis Picabia watercolor, a 1980s tapestry produced by Ateliers Pinton Frères after a design by Alexander Calder and a contemporary Bo Bartlett portrait.

To add warmth and drama to the architecturally stark space, Jayne employed inventive theatricality. Guests enter from a gold-grasscloth-clad vestibule through gates created by jeweler and sculptor Albert Paley, which are flanked by panels commissioned from the New York–based decorative painter Pierre Finkelstein, a longtime Jayne collaborator. These are meticulously rendered to give the appearance of a floral pattern seen through sheer draperies, a trompe l’oeil effect that adds depth and an updated old-world delicacy to the living area’s walls.

Finkelstein’s painting references the folding dressing screens popular in the Victorian era, says William Cullum, senior designer at Jayne Design Studio, who worked on the project. “It’s a way to decorate sheetrock walls while creating a backdrop that unfolds through the space.”

Jayne also designated one of Finkelstein’s painted panels for an alcove built to showcase a nearly nine-foot-tall 18th-century Italian Rococo secretary, which serves as a foil to the modern architecture. “As furniture, secretaries were real statements of position,” says the designer, who gained expertise in antiques while studying and working at museums (Winterthur), historic estates (Drumlin Hall) and Christie’s. “The upper cabinets were for account books, and the amount of space you had for them indicated your wealth.”

Across the room from the secretary, Jayne placed an equally imposing 1890s wrought-iron candelabra near a 1940s Steinway grand piano. “There is a great Philadelphia tradition of ironwork,” he notes. “We added gilding, so it’s pretty crazy, and I thought it might look Liberace. But it’s taller than I am [Jayne is six foot seven], and I love the reciprocity of this floral candelabra and the painted walls.”

His most audacious flourish was dividing the vast living room to create a dining area that is semi-enclosed by floor-to-ceiling architectural easels. Inspired by shoji screens and kimono stands, these room dividers are composed of panels set into chamfered oak posts rising from a plinth base, offering a place for hanging artwork. Inside the defined space, more than a dozen guests can gather around a Karl Springer table that Jayne relacquered in lapis lazuli blue — a thoroughly modern counterpoint to a suite of late-18th-century Portuguese Chippendale-style chairs with ball-and-claw feet. (The table and chairs, photographed in the client’s former townhouse, were featured on the cover of Jayne’s 2012 monograph, American Decoration.)

“The idea of having a dining room is old-fashioned,” Jayne declares. “Making this a discrete space gives the luxury of a place where everyone can sit down and focus on each other. And it allowed us to show more of the art collection.”

The designer happily admits that the effect is like a film set. “A lot of what I do has a movie underlay,” he says. “Even though I’m thought of us as being Eastern and old-fashioned, I grew up in Los Angeles. I went to a school designed by A. Quincy Jones, and my friends whose parents were in the movie business had period furniture carved on the back lots. So, I’ve always been drawn to the combination of modern and old.

“We don’t practice traditional design because we lack imagination,” he continues. “It’s because it makes people feel comfortable. So, we can riff on it, but comfort is always on our minds.”

As a result, the kitchen and primary bedroom and bath feel more contemporary than traditionalist — “light and functional,” as Jayne puts it — with decorative touches such as a large shell-framed mirror commissioned by the client in Spain and 1920s Chinese lotus jars. By contrast, the library — a cozy cocoon of pale blue with sheer cinnabar curtains — has the bohemian air of world-traveling hunter gatherers. The room mixes Bellini leather armchairs and a post–World War II glass and steel coffee table with a neoclassical parquetry card table, an Oriental carpet, a Turkish-style sofa, an early 20th-century wicker floor lamp and a pair of 1870s English Midland pottery garden stools.

“I have three or four sets,” the client says. “The shapes and sizes are different, but the decoration, whether Chinese or English, is always gorgeous. I even have a pair of miniature garden stools.”

Cullum sees in such pieces evidence of a sense of humor enhancing the client’s keen eye, adding that he is not “looking for the textbook example of a design. Each object is not exactly what you expect at first glance.”

Jayne concurs, pointing to a pair of living room side tables that combine traditional oval tops with gilded bases in the form of cranes, which the client acquired in London. “They are so beautiful and odd. Who would’ve bought them?” he asks with admiration. “And they add a special organic quality in this rigidly modern architecture.”

The tables also coordinate with a pleasingly symmetrical layout of sculptural antiques, including English Regency chairs with gilt lions’ heads and feet, ca. 1780 Italian marquetry commodes in the style of Giuseppe Maggiolini, matching sofas based on an Edwardian silhouette and two Diego Giacometti–influenced iron coffee tables fabricated by Paul Ferrante with frog finials. On the glass top of one of the tables, a ceramic frog keeps company with a prized 1730s Chinese cinnabar-lacquer box.

“Thomas Jayne requires something red and a frog in every room,” the client’s wife jokes. Jayne takes such gentle ribbing in stride. “We help collectors form livable settings for their decorative arts, using history in a contemporary way,” he says. “This apartment proves you can live well with old things.”