October 22, 2023“I don’t want to scare you, Eric, but I’m ready to do a second book,” says Pamela Shamshiri. “And I won’t do it without the team.” The Los Angeles–based interior designer is speaking to Eric Hoffman, the creative director who helped produce Shamshiri: Interiors (Rizzoli), her first monograph since she founded Studio Shamshiri with her brother, Ramin, seven years ago. The team includes Michael Reynolds, Hoffman’s partner, who styled every room in the book; Stephen Kent Johnson, who took the photographs; and two colleagues of Eric’s at Hoffman Creative: art director Chris Paolini, who came up with the template that makes the book flow rhythmically, and graphic designer Rebecca Goldberg, who laid out every page.

All of them gathered recently in Hoffman’s light-filled New York office, where Shamshiri was posing for a portrait. The only team member who wasn’t there was Mayer Rus, the West Coast wordsmith who edited Pamela’s moving essays about each of the nine projects in the book. Reynolds wrote the volume’s afterword, in which he acknowledges the relationship between the people whose work is documented in the book and the people who did the documenting. “Simply put, this book is an expression of one family rightfully and lovingly lauding the achievements of another.”

The Shamshiri family’s interest in design goes back at least as far as Tehran, where Pamela’s father ran a chic furniture showroom. (Pamela says her mother was “his muse.”) The two children often hung out at the store, Ramin writes in the book’s preface, “playing on the furniture and subconsciously absorbing all the newest designs of the era.”

That changed in 1979, when the family was forced to flee the Iranian revolution. They settled in California’s San Fernando Valley. There, Ramin, three years younger than Pamela, recalls, “our mother sometimes forced us to dress in matching lederhosen and Italian loafers, making me the target of much ridicule in the sandbox. Somehow, Pam made it work for her.”

Is there anything she can’t make work for her? After college and grad school, she spent almost 10 years as an event designer par excellence. Then, she, Ramin, Roman Alonso and Stephen Johanknecht founded the design firm Commune, which went from a 5- to a 40-person office in three years and won a National Design Award. Since then, Studio Shamshiri has taken on some highly complex interior design jobs, working in environments that run the gamut from deeply traditional to boldly contemporary. (Ramin recently left to pursue other opportunities, including developing a hotel in Ojai.)

When it came time to capture the Studio Shamshiri magic in a book, the firm’s first, she turned to Hoffman, having discovered that their “processes” are similar: Both do lots of research before actually starting to design. In Shamshiri’s case, after learning as much as she can about her client, the client’s house, the people who designed it and its surroundings, she and her team put together a concept book, which guides their decision making at every turn and, Shamshiri says, “adds layers of detail informed by deep dives into history and archives.”

Rus sees the concept books as key to the firm’s success. Describing the Shamshiri-designed Maison de la Luz hotel in New Orleans, he writes, “Guests may enter the lipstick-red Bar Marilou from the lounge through a secret door built into a bookcase,” Then he waxes metaphoric: “The hidden door is also the embodiment of how Pamela Shamshiri and her team enter into every project: through a wall of books.”

“We couldn’t show the concept books themselves,” says Hoffman, whose firm has also worked with Studio Shamshiri on its website and visual identity, “but we used some of that historical material.” By placing older images alongside Johnson’s photos, Shamshiri: Interiors reveals how the designer manages to bring the past into the present. Her work, as Rus observes in another great turn of phrase, is caught “between the era of telegrams and Instagram.”

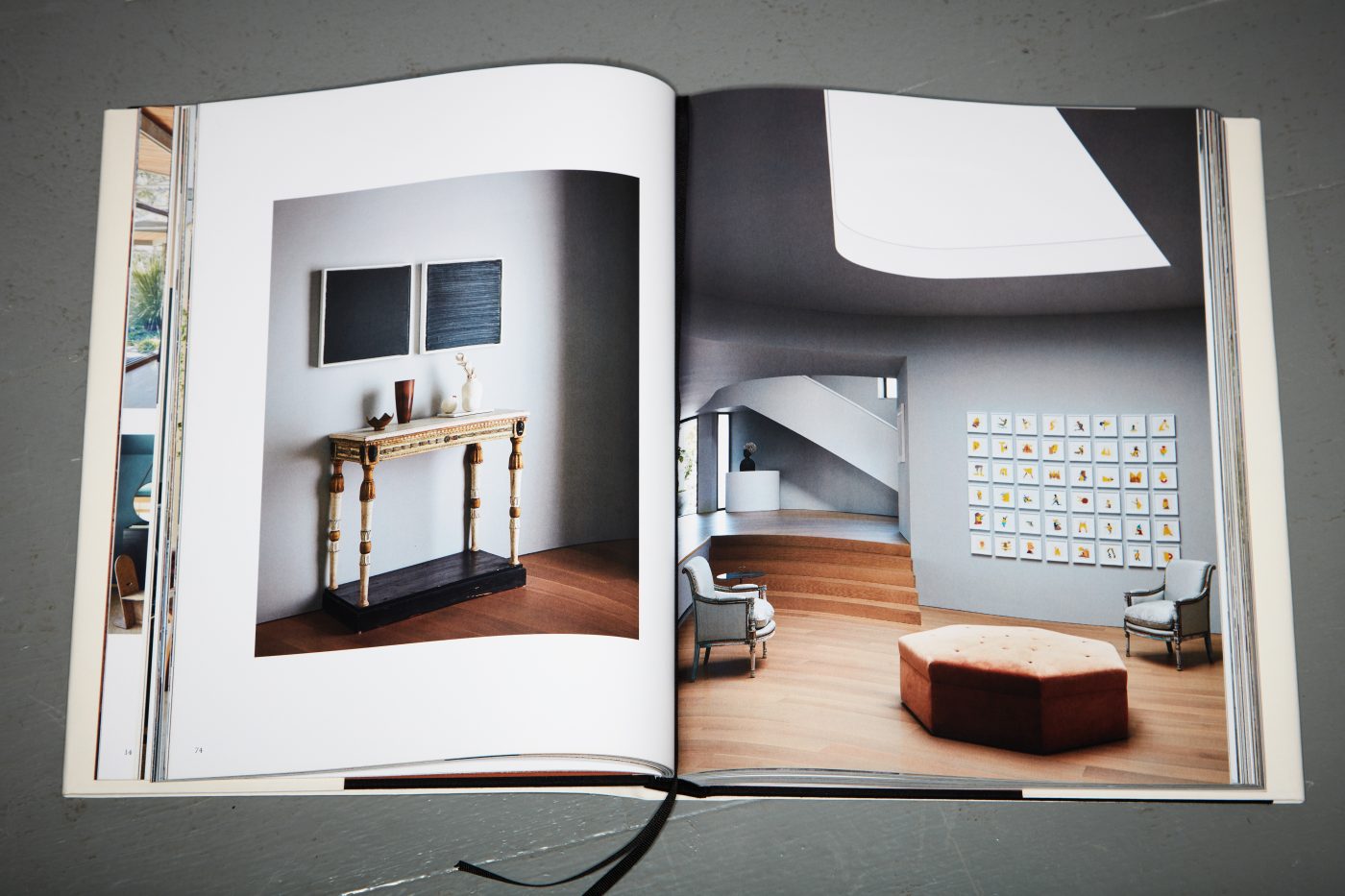

Architects Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee brought Shamshiri a decidedly Instagram-era project. A couple of Houston-based collectors had asked the partners’ firm, Johnston Marklee, to design a new house in Pacific Palisades. The architects, in turn, reached out to Shamshiri, who set out to create rooms that, while sparse (so pieces by artists like Ed Ruscha, Cindy Sherman, Gerhard Richter and Robert Irwin had room to breathe), were also cozy, “since this was a house first and a gallery second.” As she writes, “we planned islands of comfort and repose, with furniture and memorabilia firmly planted in each space.”

She started by giving every room an anchor: an unusual seven-sided ottoman in the gallery, stone bookshelves by Afra and Tobia Scarpa in the den and a curved double sofa inspired by the seating at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington in the living room. Throughout the house, furniture groupings suggest home-scale installations within museum-scale interiors.

Shamshiri has many repeat clients. One family whose New York apartment she had designed came back to her when they decided to decamp to Montecito for “greener pastures and a quieter life.” As the move to California approached, she observes, “their hair got longer and unruly, their clothes less formal, their manner more relaxed. Joni Mitchell always seemed to be playing in the background. The clients were looking at both sides now.” They had picked out a 1950s house by Cliff May, “the father of the California ranch.” Although the two were not at all alike, Shamshiri moved many pieces from the Manhattan apartment to the new residence. “I am not a fan of waste,” she explains, “and I consider this kind of adaptive reuse one of the noblest forms of recycling. It’s always fascinating to see how furniture can take on a new life and a new look in an entirely different context.”

Leaning into the clients’ desire for a retreat, she designed what are essentially treehouses for the children’s bedrooms — places for “the kids to unplug, wind down and read a book.” Maybe some of them will read this book and decide to become designers. You couldn’t blame them. It’s hard to think of another where a designer’s voice comes through so clearly.

This is true even when her clients are larger-than-life figures. Take the house Shamshiri designed for Hollywood titan Ryan Murphy (whose name isn’t used in the book but who wrote an article in Architectural Digest about working with Shamshiri on the project). Murphy’s sprawling Spanish-style compound had been renovated by one of Hollywood’s favorite designers, Stephen Shadley, with the precision Murphy requested.

When he approached Shamshiri to help furnish the house, he asked her to use only black and white. She almost complied, bringing in large objects without much color but with other compelling traits, starting with an unmissable gorilla bust by François-Xavier Lalanne. In the primary bathroom, a monochromatic plywood cabinet by Ettore Sottsass is intriguing in its extreme asymmetry. In the center of the room is a bathtub designed by the Haas Brothers that defines “showstopper.” It is carved into a shape that suggests, entirely in marble, droplets of water splashing out of the tub.

An even more challenging job was making a very large house by A. Quincy Jones, one of California’s first modernists, comfortable for a single mother of grown children. The original architecture, Shamshiri writes, “felt fixed, heavy and perhaps even oppressive at times. I wanted to do the opposite. I had a client with a strong point of view that needed to be acknowledged inside her historic landmark.” Accordingly, she chose elements that were “bold in scale, soft in shape and feminine in color.” Those words perfectly describe the plush, rose-hued, round sectional sofa in the living room, where it rests on a carpet that evokes a raked Japanese garden. Shamshiri also designed a stirringly beautiful round kitchen, something with no precedent in the house but that she believes Jones would have liked. So skillful were her interventions that, after four years of construction, a guest thanked her for not changing a thing.

For another project, updating a Palladian villa designed by architect Ned Forrest in the 1980s, she changed everything and nothing. “The design elements we focused on were color, manipulation of scale, and a more casual arrangement of the clients’ kaleidoscopic collection to make it feel fresh and ever-evolving,” Shamshiri writes, adding, in a paraphrase of Flaubert, “The role of the author is to be everywhere present but nowhere visible.”

The current book, Shamshiri says, documents “the first wave of completed work since Studio Shamshiri was founded.” As she told Hoffman, she’s ready to document the second wave in a new volume. How will it be different from the first? “I’m evolving our design to be more minimal and precise — not necessarily minimalist in style but in experience. My goal is to communicate more with less. I think with the world in the state it is in, we want a sense of place, a sense of time, a sense of safety and refuge. And we want to live thoughtfully with less.”