December 8, 2024At first glance, the offices of Breland–Harper has the minimalist architectural profile of a blue-chip art gallery. Indeed, the large front window of the building — which sits among auto repair shops, a designer-fashion consignment boutique and home-decor stores in Los Angeles’s Silver Lake neighborhood — reveals a glimpse of an exhibition of the work of Jay McCafferty, a Southern California artist who gained fame in the 1970s for using sunlight and magnifying glasses to burn stacks of paper, creating delicate grids of charred holes and smoky residue.

Pieces by McCafferty hang throughout the 7,500-plus-square-foot headquarters of the namesake architecture, landscape and interiors firm of founders and principals Michael Breland and Peter Harper. Partners in life and work, the duo collaborated on the redesign of the former warehouse, which once held Disney props, turning it into a sleek new space that now not only houses the studio of their 15-person team but also engages the community with a program of art shows.

In the 15 years since they met, the native northern Californians have earned kudos both for their their commercial projects, which center on the adaptive reuse of old factories throughout L.A., and for their residential designs, which focus on historical preservation and period-correct decor with a contemporary spin, all refracted through the lens of 21st-century Southern California living.

Their design approach, Breland says, “captures the spirit of a place and the people who live and work there. It’s always about driving the narrative forward in a way that’s contextual and appropriate.”

One example of this approach? A two-story, four-bedroom French Normandy Revival house in Brentwood that the firm reimagined for an entertainment-industry couple with two young children and the family dog. In the process, they reworked the staircase with new French-Provincial-meets-Directoire balusters that echo the front entry portico columns, updated the Art Deco-cum-Federal fireplace with a honed Belgian black marble surround and restored a streamlined Rococo moderne powder-room vanity.

Working with clients who understood traditional design but had progressive tastes, Breland and Harper — who grew up, respectively, in Berkeley and Monterey — were intent on selecting furnishings that both honored the heritage of the house and provided ease and comfort for a modern family. One influential touchstone was Frances Adler Elkins, the mid-20th-century interior decorator whose mix of antiques and modern designs made her the toast of the Monterey Peninsula from the 1930s to the 1950s.

“In her interiors, you might have a Sheraton secretary and a Jean-Michel Frank parchment coffee table in the same room,” says Harper, who leads the firm’s residential commissions, while Breland spearheads commercial ones.

In the entry to the home, Harper created a similarly harmonious Elkins-esque grouping of varying periods and styles: A 19th-century English oak table with bun feet sits opposite an iron-and-leather Frank-style console topped with a 1920s American tramp art box and a 1950s lamp by leather atelier Le Tanneur, which produced work for Hermès and Jacques Adnet.

“Antiques are critical for adding character and a layer of time to an interior,” Breland says of the furnishings, which include heirlooms from the clients’ parents and grandparents. “We wanted to create the feeling that the furniture has always been there.”

The firm designed the living room’s custom-upholstered seating with that in mind. A minimalist skirted linen sofa, scroll-arm chairs in hemp with welt edges and an English roll armchair in Rose Tarlow mohair create a timeless look in tune with the character and scale of the space.

Mixed in with these custom pieces are vintage items, including a Bielecky Brothers woven-rattan lamp table and a reclaimed-oak coffee table, slim-lined teak Danish nesting tables and a monumental glass-fronted English Regency mahogany bookcase that adds refinement to the relaxed gathering place.

Measured doses of black provide visual structure: the trim on a Federal mirror over the fireplace, a Pueblo pottery bowl and Bakelite box on the mantel, Rose Uniacke sconces, a mid-century metal-and-smoked-glass table and a lacquered spoon chair by Michael Taylor.

“Sometimes, in a room, you need what I call a lemon wedge, something acidic and beautiful,” Harper says. In the living room, the lemon wedge is Gio Ponti’s Superleggera chair. “It adds a bit of sex appeal, like a libertine,” observes Harper, who so prizes the Italian chair that he placed another one at the powder room vanity and an entire grouping of them in the cozy breakfast area adjacent to the kitchen.

The dining room features a Louis Philippe buffet and a suite of mahogany French Deco chairs around a Breland-Harper trestle table. “There’s a purity of form to Art Deco that transcends its epoch, but the goal was to use the chairs in a way that doesn’t feel too glam,” says Harper, who retained the original well-patinated leather upholstery.

Unconventional lighting — Ingo Maurer’s 1980 Flotation pendant, made of crinkled Japanese paper, and a vibrant blue lamp by L.A. ceramist Victoria Morris — helps dial down any formality, as does the placement of the artwork. “We hung a painting by the L.A. artist Anna Ullman so that it interrupts the dado rail on the paneled wall, which gives a contemporary look,” says Harper.

Similarly, painting the rough-sawn, tongue-and-groove paneling of the library in a solid sage green gave a more modern feel to what, with its flagstone fireplace, had been a rustic room. The space, which serves the homeowners as a place for both teleconferences and family hangouts, now also sports a leather-clad ottoman with George IV legs and brass casters and a comfortable skirted sofa, both Breland-Harper designs. Flanking the sofa are two claro-walnut cubes by the Los Angeles woodworker John Pope, which are adorned with ceramics by Morris.

“Contemporary art, crafts and furniture design are fundamental to our projects,” Breland says. “And we are always striving to find local makers we can work with.”

In another project, a gut renovation of a neglected 1965 post and beam in Pasadena, Breland-Harper employed all the firm’s disciplines to reconceive and reinvigorate the home and gardens. The idea, Harper says, was to create “a mid-century pavilion deeply inspired by the architect Vladimir Ossipoff’s distinct brand of tropical modernism in Hawaii.”

Using the existing mature trees on the property as “poles,” for the landscape, he explains, “we focused on plantings arranged in expansive drifts across the large property to create movement and a range of experiences.”

The team added flagstone floors and natural-wood millwork ceilings inside the house, which, together with the home’s multiple terraces and balconies, cement a visual connection between indoors and out. This organic interplay is reinforced by what Harper refers to as “wonderfully broken-in and patinated” vintage furniture by Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, Hans Wegner, Clara Porset, Bodil Kjær and George Nakashima.

“The soul of the decor is the profound beauty of East Asian objects from the eighteenth to twentieth centuries that bridge the built world and the natural world in a poetic way,” Harper says, pointing to examples like a Japanese kiri-wood tansu chest on a staircase landing and, in the dining room, a vintage Japanese screen found stripped of its silk surface, revealing the newsprint papier-mâché and wood lattice beneath.

Breland and Harper’s love of finely crafted works can be traced back to their childhoods. Harper’s mother decorated the family’s 1950s white-clapboard home with, among other items, a Chippendale dining table, a camelback sofa, a Gustavian cabinet, an early-19th-century linen press and an ormolu clock. “Her magpie collecting really influenced me,” he recalls. “She didn’t see a difference between a Meissen plate and a seashell.”

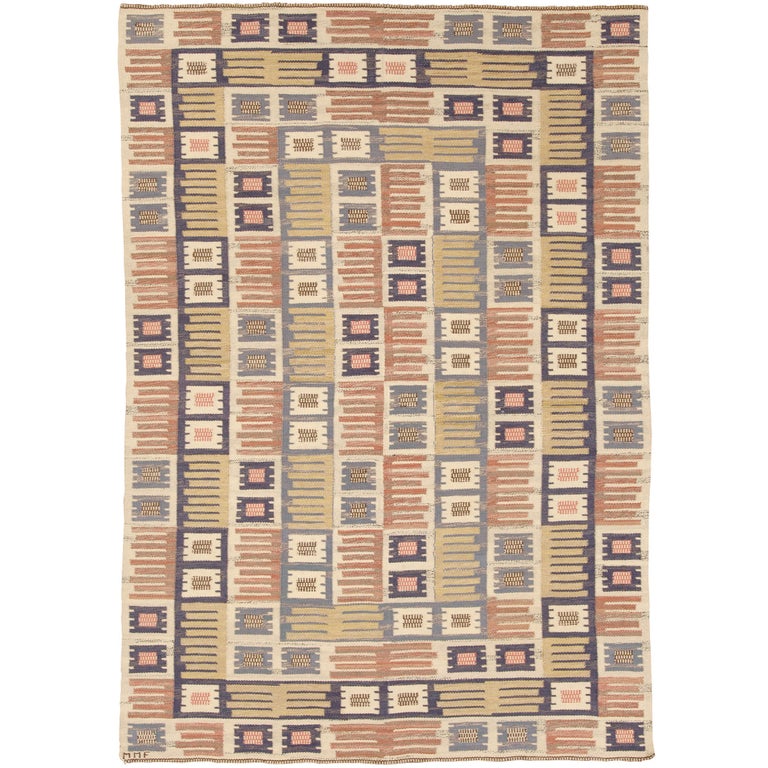

Breland grew up in a Berkeley Arts and Crafts home of a simplicity akin to that of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses. His parents decorated with Donghia furniture, Persian carpets and ethnographic and contemporary art.

The pair met as architecture students at the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles, where they developed the intellectual rigor and encyclopedic grasp of design history that informs their work. “We were knee-deep in the whole Rem Koolhaas Prada era,” Breland remembers. “And we sat outside the program and challenged the norms.”

After earning bachelor of architecture degrees, in 2010, they moved to New York City, where Breland freelanced while Harper completed masters degrees in historic preservation and architecture at Columbia.

Breland left to work at Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation, in Marfa, Texas, before the duo returned to Los Angeles, in 2013. Three years later, after executing successful commercial design-build projects while with a midsize design-build firm in L.A., he launched his own studio, which Harper joined officially in 2019.

After living in two houses they designed and built together, they have settled in a 1920s Spanish Revival home in L.A.’s Los Feliz neighborhood, which they share with “a moose of a standard poodle named Henry,” Harper says with a smile.

“Your home and what you put in it are among the largest external points of communication you make about your life,” continues the designer. In furnishing their home, he mixed a Christian Liaigre Basse Terre sofa and American primitive furniture that the couple has had for years with an 18th-century Tuscan walnut Fratino table and 17th-century Spanish baroque pieces selected to play up the Mediterranean architecture. “Our hope is that our house telegraphs unrestrained openness and abundant kindness.”

One abundantly kind gesture the designers swear by is mood lighting. “For us, and for people who work in front of computer screens all day, calibrating light is the most immediate way to help people relax,” Harper says.

Breland wholeheartedly agrees: “If you come to our house for dinner, there won’t be a single light on.” Indeed, the couple and their guests gather around an early-19th-century scrubbed-oak English pedestal table, each seated on a linen-slipcovered custom chair or an early- American rush-accented one. And, Breland continues, “we eat exclusively by candlelight.”