May 3, 2020When you name your business after an ancient chair, you’re telling the world you’re committed to classicism.

Collier Calandruccio will tell you so directly, too. “It’s in my DNA,” he says of classicism and other traditional forms. The affable 32-year-old Tennessee native has been steeped in these styles since childhood. Thus the name of his by-appointment-only gallery, Klismos, which he launched in 2017 in Brooklyn with the tagline “Classicism for the 21st Century.”

The name, of course, refers to the klismos chair, whose familiar contours —curved splat and tapering, curving legs — were developed in Greece around the 5th century B.C. In the mid-20th century, the form was chicly tweaked by T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings, demonstrating how durable it is. The piece, like classicism itself, remains perennially popular today.

Many of the furniture pieces and decorative items that Calandruccio sells are from the 18th and early 19th centuries a period when neoclassicism flourished in Europe and the United States. Among his current offerings — which he artfully arranges on the light-filled parlor floor of an 1899 Renaissance Revival townhouse in the Crown Heights Historic District — is a finely carved 18th-century Gothic-style Chippendale mahogany side chair. Made in England around 1770, it sports the original 250-year-old finish and new gray velvet upholstery.

But like a true devotee, Calandruccio has his eye trained on the full range of classicism. “Our oldest piece is an Egyptian statue from fifteen hundred B.C., and our most recent piece is a 1978 Robert Mapplethorpe photograph,” he says.

Calandruccio grew up in Memphis and earned a bachelor’s from Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, going on to study at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation.

He benefited from the South’s tradition of well-preserved antiques and historic architecture. “I grew up visiting old family houses in Virginia and Mississippi,” he says. “And I attended the same church that my family’s gone to since 1832, in a Gothic Revival building. So my eye’s been trained to it all along.”

No one would question his ardor — “It’s all I think about, live and breathe,” says the gallerist, an active member of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art — but we did ask him about some other subjects.

What about your offerings makes them stand out?

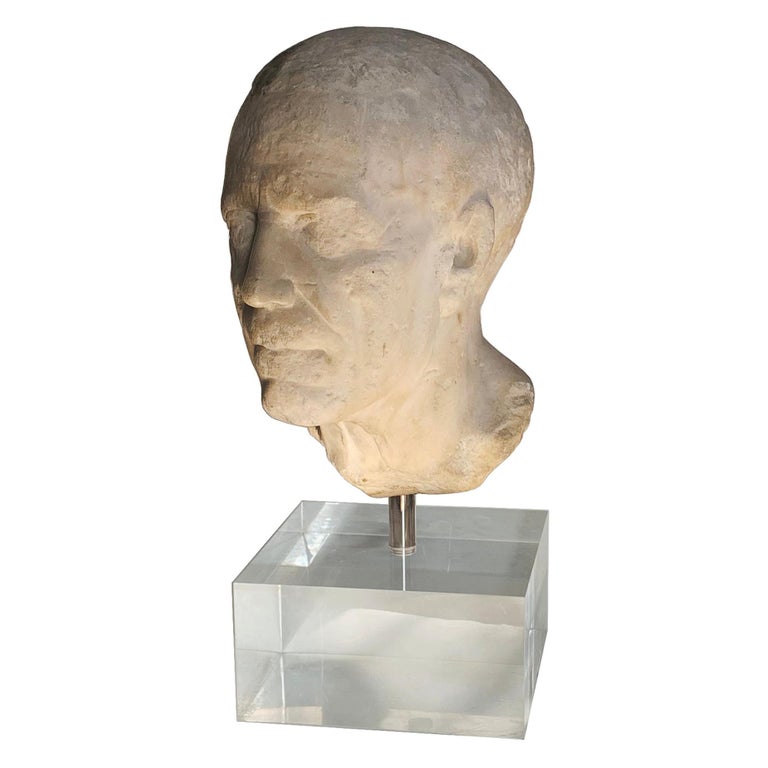

I try to find things that are undiscovered and that are truly meaningful, as opposed to just being purely decorative. So, I was very lucky to discover an Archaic Cypriot classical bust. When I found it, it was listed as being a plaster copy, when in fact it was one of the most important pieces to come to light of its type. It has almond-shaped eyes and a Persian-style beard — it’s a fusion of Persian and Hellenic elements. It’s one of the most exciting discoveries we’ve had.

What is a typical buyer most interested in?

Larger, architectonic case pieces, often Biedermeier or Georgian, which historically have not moved that quickly. For a while, armoires were used to house TVs, but I think now people are getting back to their intended use as storage. Designers are increasingly asking if hanging rods are present or could be installed for their clients. One of the first pieces I bought for myself after moving to New York was a mid-eighteenth-century English livery armoire. I now hang my suits and sport coats in it. Wrought-iron hooks that once held bridles and other tack in an English country house now hold belts and neckties.

What’s one piece that got away?

My biggest regret is selling a beautiful American girandole mirror, made by Isaac Platt in New York about 1820. It was one of the finest examples of that sort of frame that I’d ever seen. And it’s now in a villa on Lake Lucerne. It was just in perfect condition. It exemplifies effusive, beautiful, high-American design. I wish I could’ve held onto it.

If you could meet any great designer of classical objects, who would it be?

Karl Friedrich Schinkel [Prussian architect, painter and furniture maker, 1781–1841]. He belonged to this movement in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when European artists and architects gained a clear archaeological understanding of classical antiquity. While firmly rooted in academic rigor, he developed designs of fantasy and sublime beauty that, in my opinion, beat the Greeks at their own game. I am always hunting for pieces that blend this spirit of respectful hindsight with their own fire and vitality. We currently have in our inventory a circa 1840 American suite of iron garden seating modeled after some of Schinkel’s designs.

What’s a mistake that buyers of classical pieces — or anything else — often make?

For contemporary collectors and designers, provenance seems to play a decreasing role, and decorative value is on the rise. Certainly, beauty has its place, but preserving an object’s history endows it with power and meaning. Part of my mission is to promote the importance of stewardship, memory and story telling. If there is a history associated with a piece of furniture or artwork, preserve it any way you can.

In this time of quarantines and lockdowns, we are presented with the opportunity to reevaluate how we spend our time and what we deem worthwhile. I hope we will seek out the sustainable and time-honored rather than settle for the superficial and fleeting.

Talking Points

Collier Calandruccio shares his thoughts on a few choice pieces