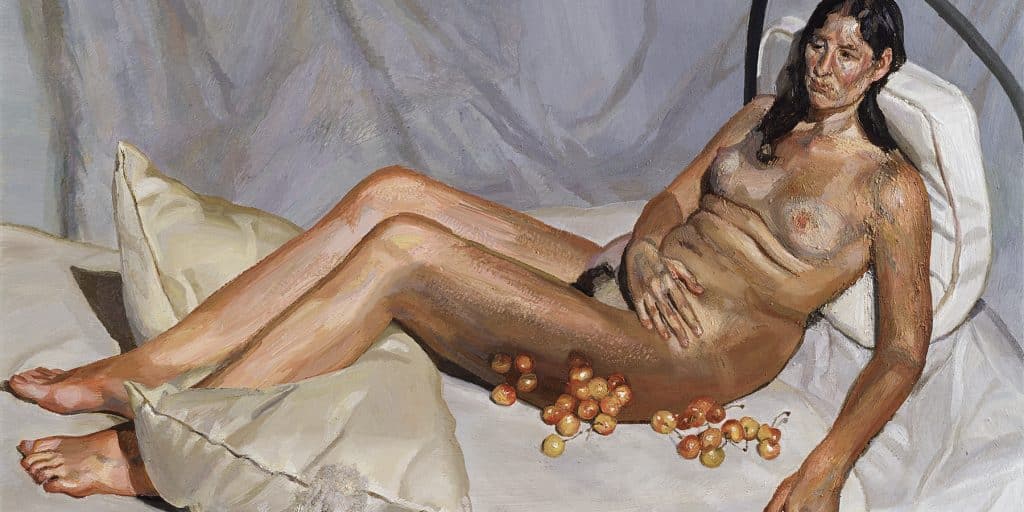

April 14, 2019New York’s Acquavella Galleries recently opened “Lucian Freud: Monumental,” the first exhibition of the British painter’s work initiated since his death, in 2011 (photo © David Dawson / Bridgeman Images). Top: Irish Woman on a Bed, 2003–04 (image © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images)

If you were the sitter, you were the most important person in the world for Lucian,” says David Dawson, director of the Lucian Freud Archive and former studio assistant to the prominent British painter, known for his visceral, acutely observed portraits. “That’s a very strong feeling, when someone pays that much attention to you. He wanted to know everything about you and how you moved.”

Dawson modeled for around 10 paintings during the two decades he worked for Freud. Entrusted by the artist to manage his copyrights, Dawson has organized the first exhibition of his work initiated since his death, in 2011 at age 88. “Lucian Freud: Monumental,” on view at New York’s Acquavella Galleries through May 24, comprises 13 larger-than-life-size naked portraits from the 1990s and 2000s that have never before been seen together and are on loan here from museums and private collections.

The show comprises 13 large-scale nude portraits painted in the last two decades of Freud’s life, among them Portrait on Gray Cover, 1996. The works have never previously been shown together.

The earliest piece in the show is Leigh Bowery (Seated), 1990, an eight-by-six-foot painting of the outrageous, corpulent performance artist, who stares down the viewer, his arm and leg draped insouciantly over one side of his chair. This is the picture Freud was working on in his London studio the first time Dawson stopped by, in 1990 at age 30. Recently graduated from the Royal College of Art in painting, he was working as the errand boy for James Kirkman, the artist’s dealer at the time.

Performance artist Leigh Bowery poses in Freud’s studio for Naked Man, Back View, 1992, which is featured in the show. Photo by Bruce Bernard © Estate of Bruce Bernard.

Model Jerry Hall and her newborn son, Gabriel, originally sat for the breastfeeding figure and baby in the background of Large Interior, Notting Hill, 1998. But Hall didn’t feel up to sitting for Freud long enough for him to finish the work, so Dawson stepped in to replace her. Image © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images

“That painting really stopped me in my tracks — I thought, ‘Nobody is painting better than this anywhere,’ ” says Dawson, who lived nearby and soon began to work full-time for the then-69-year-old Freud. “I could see he was giving himself the biggest last push, as a man and as an artist. The dynamic of our friendship was ‘I’ll just sort out everything in your life, and all you need to do is paint.’ ”

Freud’s series of Bowery portraits — another of which is in the show, on loan from the Metropolitan Museum — signaled a massive scaling up in size of the painter’s pictures, often involving an extension sewn onto the canvas. Rather than letting the limitations of the shape and size of the canvas influence his forms, Dawson says, “if the forms within the painting and body demanded more space, Lucian would just add canvas.”

Freud had intended to paint Bowery, known for dressing up flamboyantly at nightclubs, in one of his signature outfits. But the performer arrived for his first sitting while the artist was on the phone and, apparently assuming he’d be posing for a nude portrait, had stripped down by the time Freud came in to paint. “Leigh obviously had it in his head how he wanted to be seen, and Lucian would never tell anyone what to do,” says Dawson, whose responsibilities included readying the studio for Freud’s marathon painting sessions, which always took place behind closed doors. “His job was to pick the person in the first place. After that, he wanted you to be you. That’s why the paintings took an awfully long time.”

Freud poses in his studio with art handler Ria Kirby, who sat for the work that would become Ria, Naked Portrait, 2006–07, also in the Acquavella show. Photo © David Dawson / Bridgeman Images

Freud was introduced to Sue Tilley, seen here in Sleeping by the Lion Carpet, by Bowery. Image © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images

Freud’s artistic process could stretch out over one to two years. So, before selecting a subject, he would gauge the personality of his prospective models to see if they were up to the commitment. Typically, he worked on four paintings at a time, with one daytime and one evening sitter posing part of the week and the rest of the week devoted to another set of models. “Day pictures never mixed with night pictures, which meant electric light, different color,” says Dawson. “He worked seven days a week, every day of the year.”

Freud painted his friends, his lovers and his children (he fathered many by several women but never lived with any), as well as people who interested him. Among those in the last category was the voluptuous Sue Tilley, whom he met through Bowery. The exhibition features two portraits of her sleeping. “He didn’t want to make this a circus act. He wanted to show this is a real person who happens to have a bigger size,” says Dawson. “He brought a very contemporary attitude to the naked portrait. It wasn’t an idealized nude. He hated that word, nude. He gives an awful lot of respect and delicacy and empathy to the person.”

Six years into their relationship, Dawson received the long-hoped-for invitation from Freud to sit for a large painting. That work, Sunday Morning — Eight Legs, 1997, on loan from the Art Institute of Chicago, shows his lean form splayed out on a bed with Freud’s dog, Pluto, plus two additional knobby knees poking out from beneath the bed. “Those are my legs under the bed as well,” says Dawson, who suggested that he crawl under there to pose when Freud was looking for an element to bring life to the bottom of the canvas. “He came out of a surrealist generation. I knew his humor.”

Dawson captured gallerist Bill Acquavella — who began showing the artist’s work in 1992 — as he sat for Freud’s etching The New Yorker, 2006. Photo © David Dawson / Bridgeman Images

Dawson also sat for Freud for Sunny Morning, Eight Legs, 1997. The extra pair of knees poking out from under the bed was Dawson’s idea.

In Large Interior, Notting Hill, 1998, the author Francis Wyndham sits in the foreground, clothed and reading, while in the background, Dawson appears to be breastfeeding. Initially, it was Jerry Hall who was posed there, with her newborn, Gabriel, but the famous model started feeling unwell and couldn’t keep up with his rigorous schedule of sittings, which really agitated Freud. “It was right at that moment when the painting might collapse, so Lucian just put me in place,” says Dawson. “It’s my head and shoulder, but that side with the baby suckling is all Jerry. When you see the painting, it’s brilliant.”

He describes his working friendship with Freud as the closest he’s ever felt to someone. “Lucian was a fantastic conversationalist,” says Dawson. “You could ask him anything and get an amazingly intelligent answer back — an observation about the capacity of the human psyche and what we’re capable of.”

The charged dynamic between painter and sitter and the psychological intensity of the resulting paintings make it tempting to draw parallels between the artist and his grandfather Sigmund Freud. “Lucian was very fond of his grandfather, but he would deny a connection,” says Dawson. “I think we can see a similarity between the one, who was having you lie on the couch and tell your innermost feelings, and Lucian, who would have you lying on the couch without any clothes on talking about the same things. But the goal was different. Sigmund Freud was trying to make people better. Lucian was making art.”