April 29, 2018Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos’s new show celebrates the work of London jewelry designers in the 1960s and ’70s. Here, she wears items from her personal collection: earrings by Afro Basaldella for Masenza, ca. 1950; and a forma livre carved-amethyst and gold necklace by Roberto Burle Marx, ca. 1960. Top: An array of lapis, diamond, enamel and 18-karat gold rings by Kutchinsky, ca. 1970. Photos courtesy of Mahnaz Collection

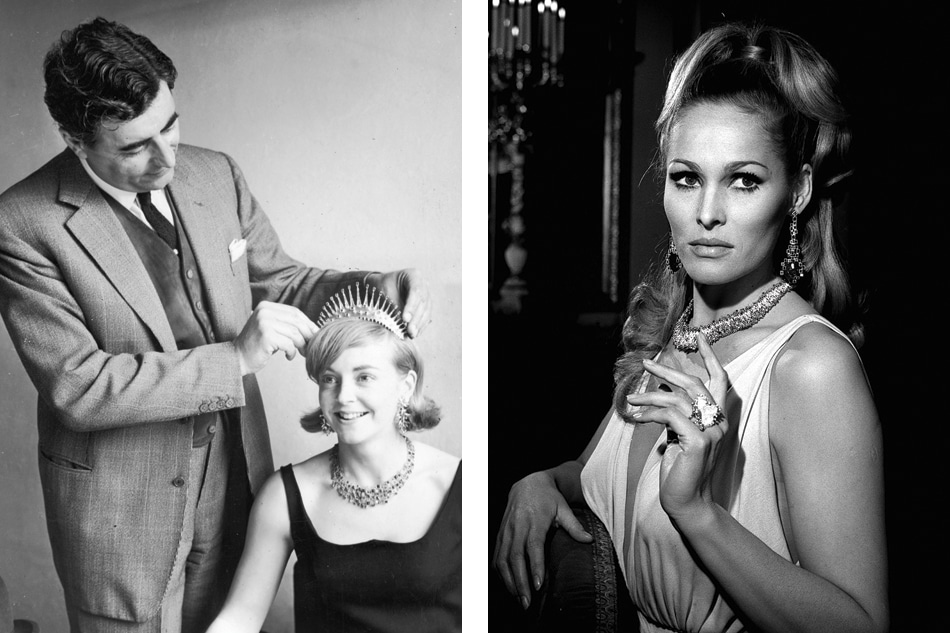

Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos’s first watch was a black and gold Omega De Ville, a gift from her mother. It was inspired by Omega’s About Time collection, created by jeweler Andrew Grima in his heyday, during London’s Swinging Sixties, when his clients included both royalty and movie stars.

The watch, a treasured part of the Pakistani-born, New York–based jewelry dealer’s personal trove, ignited a passion for mid-century design that still burns today.

This passion has led her to present “London Originals: The Jeweler’s Art in Radical Times,” a comprehensive exhibit of 150 pieces created in the British capital during the 1960s and ’70s. It celebrates a period of energy and excitement in jewelry design that occurred against a backdrop of massive cultural and social upheaval.

The exhibition, which earlier this month was hosted by the Wright gallery in Manhattan, is now on view at Mahnaz Collection’s own penthouse gallery, at 32 East 57th Street. Timed to coincide with TEFAF New York Spring (running from May 4 through 8), it has expanded in its new venue to include Ispahani Bartos’s collection of jewels by groundbreaking non-British designers of the same vintage, such as Finland’s Björn Weckström and Denmark’s Nanna Ditzel.

“It was a truly innovative period, and it came out of the times they were in. So many other things were changing,” says Ispahani Bartos.

At the end of the 1950s, the London jewelry trade was stagnant, battered by the war and its prolonged aftereffects. Materials such as platinum had been requisitioned for the war effort, and a high luxury sales tax stifled business. Design, too, was in the doldrums, the prevailing fashion being for literal animal and flower designs bedecked with a smattering of diamonds.

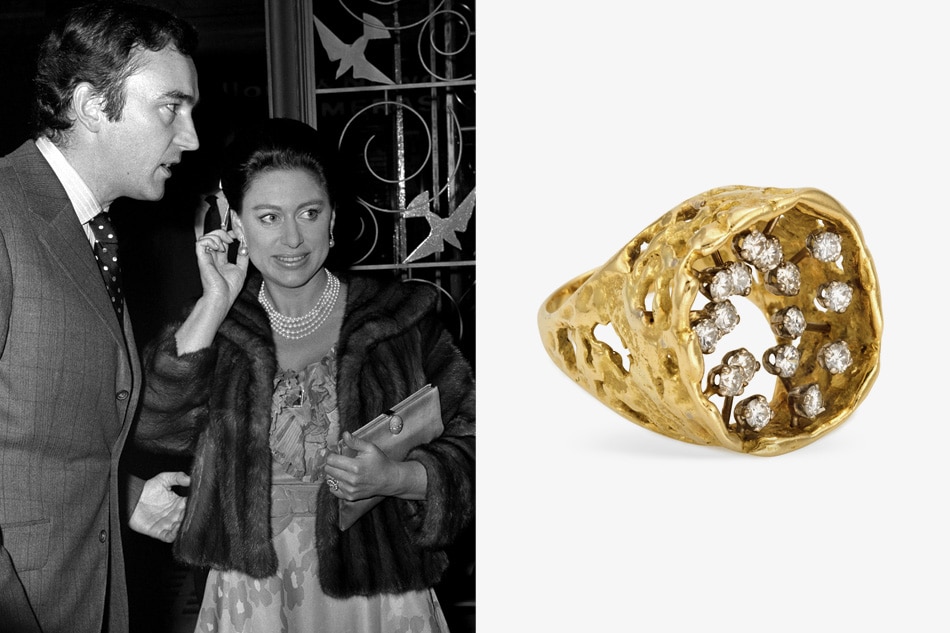

With their textured gold, sculpted forms and unconventional semiprecious stones in electric hues, the pieces by such British jewelers as Grima, George Weil, Gerda Flöckinger and John Donald, who emerged at 1961’s “International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery 1890–1961” at the city’s Goldsmiths Hall, felt like a breath of fresh air. “Suddenly there was an uninhibited attitude to what jewelry could be,” says Ispahani Bartos.

John Donald designed this 18-karat gold nugget flake necklace with diamonds and a pear-shaped pink tourmaline cabochon, 1998. Photo courtesy of Mahnaz Collection

A piece by Donald featured in “London Originals” is a case in point. A sculpted collar centering on a giant cerise pear-shaped tourmaline, with cutouts in the gold revealing sensual flashes of collarbone, it exemplifies the period’s sense of daring as well as its unadulterated glamour. “I love the way he molded the gold, the way he pierces it in that very irregular way, the choice of unusual and very beautiful colored stones,” Ispahani Bartos says.

She gives credit to Graham Hughes for the groundbreaking concept underlying the 1961 exhibit, which he curated in collaboration with the Victoria and Albert Museum. Hughes, the art director of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths (a London guild established in the Middle Ages) had decided that the show should represent different kinds of jewelry to emphasize the discipline’s artistry in design, no matter the materials used.

“It went from Fabergé and Harry Winston to Grima,” says Ispahani Bartos. “He put diamond necklaces in a display cabinet with far less valuable jewelry and asked the question: Does the material speak to its value as a jewel, or is it the design?”

“It was a truly innovative period, and it came out of the times they were in. So many other things were changing.”

Jewelry designer Gerda Flöckinger in 1968, by © Julian Nieman/National Portrait Gallery, London

The question is still relevant today, she adds, pointing to the work of Hemmerle. The German artist-jeweler, widely regarded as one of the most talented in the world, mixes wood, aluminum and iron with diamonds and colored gems in outstanding designs that are precious in themselves.

Of those British jewelers who paved the way 50 years ago, few are widely known today. Although Grima has enjoyed a resurgence of interest from collectors in recent years, Ispahani Bartos sees it as her mission to spread the word about the others to contemporary jewelry lovers.

She has spent the past several years tracking down the makers of pieces to which she was first attracted by their designs. A striking carved-lapis turban-form ring, for example, she wound up attributing to EJ Shewry, a small London jeweler. Such research can turn up unexpected delights. She fell for an unnamed emerald and peridot bracelet shaped like a shirt cuff that she knew was made for Wenda Parkinson, the actress and wife of photographer Norman Parkinson.

Ispahani Bartos ultimately discovered that its designer was Jon Bannenberg, once Britain’s foremost luxury yacht designer. The bracelet encapsulates another of her loves for the period, which is that these artists were not restricted to one discipline but had free rein to express themselves in multiple media. “That appeals to me a great deal,” she says. “These times have become much more specialized, and it’s hard to see that dexterity across fields today.”

An example of the earlier generation’s cross-disciplinary dexterity is Brazilian designer Roberto Burle Marx, who created similarly radical jewels during the 1960s and ’70s with his lapidary brother, Haroldo. Roberto was also an abstract painter and landscape designer who invented the field now known as tropical modernism.

Left: A diamond and 18-karat gold bracelet, earring and ring set by David Thomas, 1972, from the limited-edition Atlantis collection for Prestige Jewellers. Right: Two modernist Kutchinsky pendants from 1971 in 18-karat yellow gold and agate, and textured 18-karat yellow gold and mirror-finish white gold. Photos courtesy of Mahnaz Collection

Wherever these mid-century creators were based, Ispahani Bartos says, their pioneering designs and exquisite craftsmanship contrast with the conventional, mass-produced jewelry that can be found in stores today. The earlier work could involve “taking a seashell and embedding it in an exquisite gold frame,” she says, “but it is always done at a very high level of workmanship.”

Visit Mahnaz Collection on 1stdibs