November 28, 2021After spending more than 30 years designing houses rooted in tradition, the celebrated architects Mark Ferguson and Oscar Shamamian have no need to blow their own horns. So they titled their latest monograph, recently published by Rizzoli, Collaborations and focused on the artists and designers they have partnered with on an extraordinary range of dwellings.

One of those collaborators is the Los Angeles–based interior designer Michael S. Smith, with whom the pair’s firm — known as Ferguson & Shamamian — has produced some 50 homes, an astonishing number given the amount of work that goes into each project. “That’s two or three a year for about twenty years,” Smith notes during a phone call from California.

These include dozens of Manhattan apartments, as well as an Arts and Crafts–style house in Westchester, a Spanish Revival mansion in L.A., a coral-covered Colonial house in the Bahamas and a Belgian-inspired lodge in Aspen — all of which diverge, deliberately, from their nominal styles.

“They’re who I go to to push the envelope in interesting ways,” Smith says of Ferguson and Shamamian, noting that, luckily, they’re not rigid or humorless, like some classical architects. “They know all the rules, and they’re comfortable breaking them.”

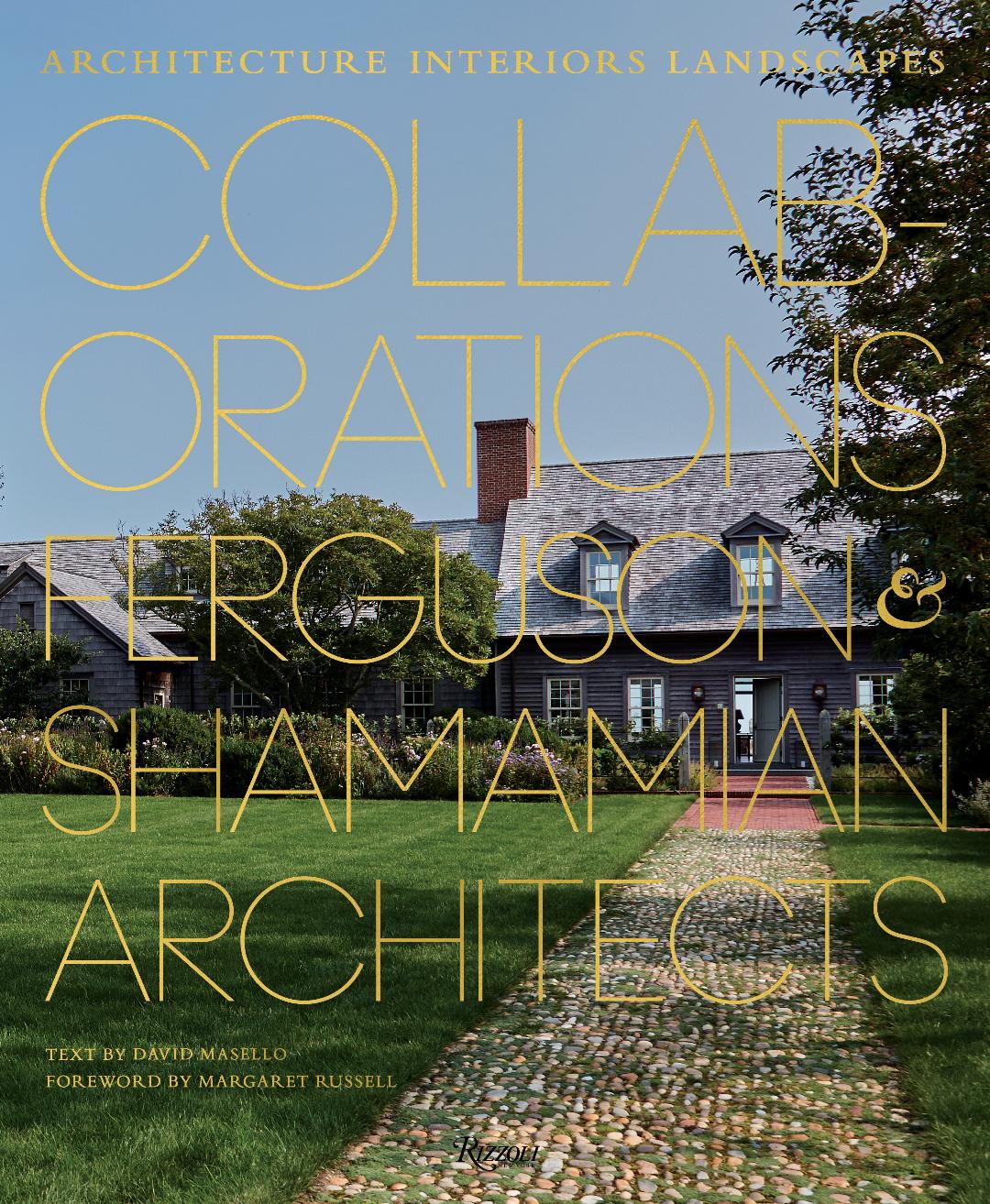

That certainly describes the duo’s approach to their most recent collaboration with Smith — a rambling family compound in East Hampton.

Ferguson & Shamamian partner Stephen Chrisman, a 26-year veteran of the firm, explains that the client asked for a simple saltbox house, one that could have been built within 100 years of the town’s founding, in 1648. But no old saltbox could contain the amount of space he and his family required — some 10,000 square feet.

So, Chrisman recalls, “Michael had the idea of exploring how a simple building might have been added to over time,” with various extensions using successively newer materials and methods. “It was a pretty powerful idea,” he says, and it provided the firm with an “excuse” for giving parts of the house bigger windows and cleaner lines than would be found in an authentic 18th-century dwelling.

Five years after the plan was hatched, the site indeed holds a saltbox, containing a great room with living and dining spaces. But it is flanked by a bedroom wing on one side and a kitchen wing with screened porch on the other.

From the kitchen, a breezeway leads to a smallish stone structure that houses a guest room. (There are several additional guest suites in a separate, barn-like building.) These “additions” could be 19th- or early- 20th-century, Chrisman says. “They’re not seventeen twenties. The classical language has evolved over the years.”

The front of the saltbox — ostensibly the oldest part of the house — has classic nine-over-nine windows and is sheathed in narrow clapboards. Chrisman based some of the dimensions on those of the nearby Home, Sweet Home, a real 1720s saltbox maintained as a house museum. “We went and measured the shingles and the clapboards,” he says.

On the rear facade of the saltbox, he adds, “the details are still traditional, but the scale shifts.” In the designers’ fictional narrative for the house, the back wall was modified when the “original” building was already more than 200 years old.

Here, the windows no longer have small panes. They’re triple-hung, without muntins. “They’re large but they’re still operable,” says Chrisman. “You can lift them and walk right outside.” Open or closed, they offer clear views of the dunes and the ocean beyond.

While designing the building’s wooden structure, which is on full view inside the great room, Chrisman studied drawings and photos of actual 18th-century framing. Then, he found the necessary reclaimed wood and had it limewashed to make it look even older than it is.

They designed ceiling joists with notches in them, suggesting that an upper floor had been removed. Ambient lighting comes from tiny spotlights painted to match the color of the beams. Obviously modern fixtures would have been jarring in this putatively antique setting.

But even in this “oldest” part of the house, Smith didn’t try to find age-appropriate furniture. Instead, he echoed the building’s handmade quality by commissioning pieces from artisans in the U.S. and abroad. The LADDER-BACK CHAIRS are from London’s JAMB. The leather and bronze FIREPLACE SURROUND is the work of Parisian artist Ingrid Donat. Smith himself designed the chevron-patterned rug in the great room, an island in a sea of antique oak.

Upstairs, the architects and designer decided to separate the library from a sometimes-noisy stairwell with a wall of casement-style windows. This intervention, more industrial than agrarian, is one of the ways Smith and the architects showed that this isn’t a period piece. “We were playing with the idea of what a country house could be,” says the designer.

For the same reason, he hung a painting by Alfred Leslie, a second-generation Abstract Expressionist, on the glass, injecting sophistication into a rural setting. A mix of other artworks are displayed throughout the house, including a Ben Nicholson painting in the main bedroom and an Alexandre Noll sculpture in the dining area.

“The clients are patient and generous,” says Smith, who commissioned a table for the breakfast room from George Nakashima Woodworkers. The mud room features a much earlier Nakashima table on a Swedish kilim rug from Mansour. (The space’s concave mirror is from Valerie Goodman Gallery.)

For the main bedroom, Smith liked the idea of a SHAKER bed — but one pushed into the realm of “interesting and personal.” So, he had one cast out of “a couple of thousand pounds of bronze.”

Smith wasn’t the only collaborator on the project. The renowned British landscape architect Arne Maynard, who had never done a private home in the U.S. before, made the property look like one cultivated for generations. An orchard, for instance, has gaps in its neat rows, as if some trees had died long ago.

Commenting on the pleasures of working with Ferguson & Shamamian, Smith told former Architectural Digest editor in chief Margaret Russell — who interviewed him for the book’s foreword — that “the entire team is seriously task-oriented and able to handle any surprises. It’s a culture of calm.”

But within that culture of calm, there are serious — and generous — design minds at work. (The firm now has six partners and employs nearly 100 architects.) As Mark Ferguson and Oscar Shamamian write in the new book, each project involves scores of people coming together to create “a portrait of the client, and not one of themselves.”