May 18, 2015Throughout “Latin America In Construction: Architecture 1955–1980,” sketches, photographs and blueprints are juxtaposed with architectural models (photo © 2015, The Museum of Modern Art). Top: Brazilian master Oscar Niemeyer, named director of architecture and urbanism for the country’s capital, Brasilia, worked with urban planner Lucio Costa on an especially sculptural design for the city’s cathedral, seen here under construction (photo courtesy of Arquivo Público do Distrito Federal).

In the 1960 update of his influential pre-war treatise, Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius, the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner slammed Brazilian architects for trying to satisfy “the craving of the public for the surprising and the fantastic, and for an escape out of reality.” But that very effort is what makes some of the 20th-century’s Brazilian architects important — and explains why their work (surprising! fantastic!) belongs in a great art museum.

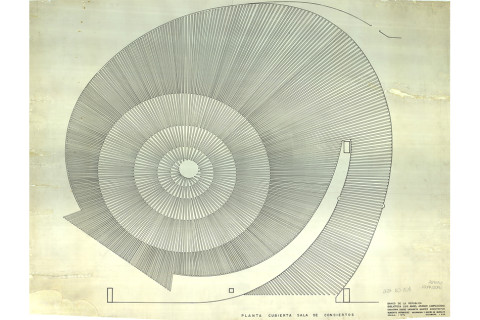

Indeed, it turns out that surprising and fantastic architecture was being created across Latin America over the course of the last century. But it rarely got the attention it deserved. That’s precisely why a new exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art — “Latin America In Construction: Architecture 1955–1980” (on view through July 19) — is so significant: Barry Bergdoll and his three South American co-curators, Patricio del Real, Carlos Eduardo Comas and Jorge Francisco Liernur, have created an eye-opening show about an unusually fertile period in an unusually fertile region.

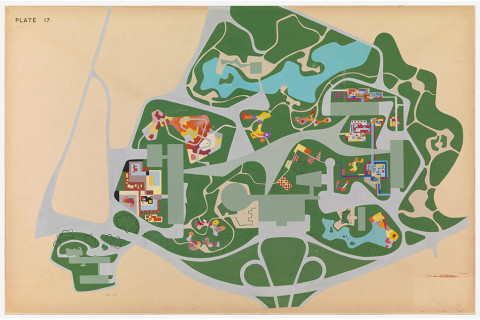

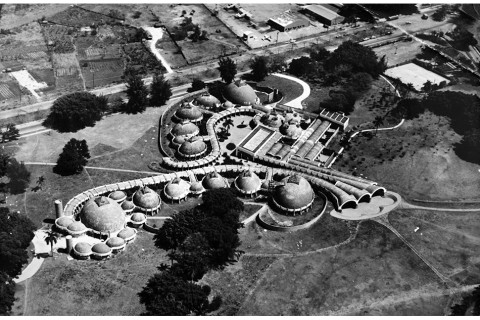

Bergdoll, who resigned as MoMA’s chief curator of architecture and design in 2013 but continued to work on this show, sought out material during repeated trips to Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. The first of the exhibitions’s large rooms (which are organized roughly by chronology) sets the stage: On one wall are images of the studio designed by Mexican painter and architect Juan O’Gorman for compatriot Diego Rivera in 1954. Rivera was a communist, and it’s no surprise that his studio, in its blocky Corbusian whiteness, resembles spare factory housing. On the opposite wall is a 1953 park design by Roberto Burle Marx, the Brazilian landscape architect who trained as a painter and brought the flourishes and energy of Abstract Expressionism to public and private spaces.

It’s fitting that O’Gorman and Burle Marx face off: The show contains hundreds of projects, all of them informed by the former’s monastic neutrality or the latter’s psychedelic exuberance — or in some cases, by both.

Colombian architect Rogelio Salmona’s iconic Park Towers, a complex of affordable housing for middle-class families in downtown Bogotà, completed in 1970, embodied one of the most prominent Cold War–era ideological battles in Latin America: how governments should deal with precipitous growth in urban populations. Photo © 2015, The Museum of Modern Art

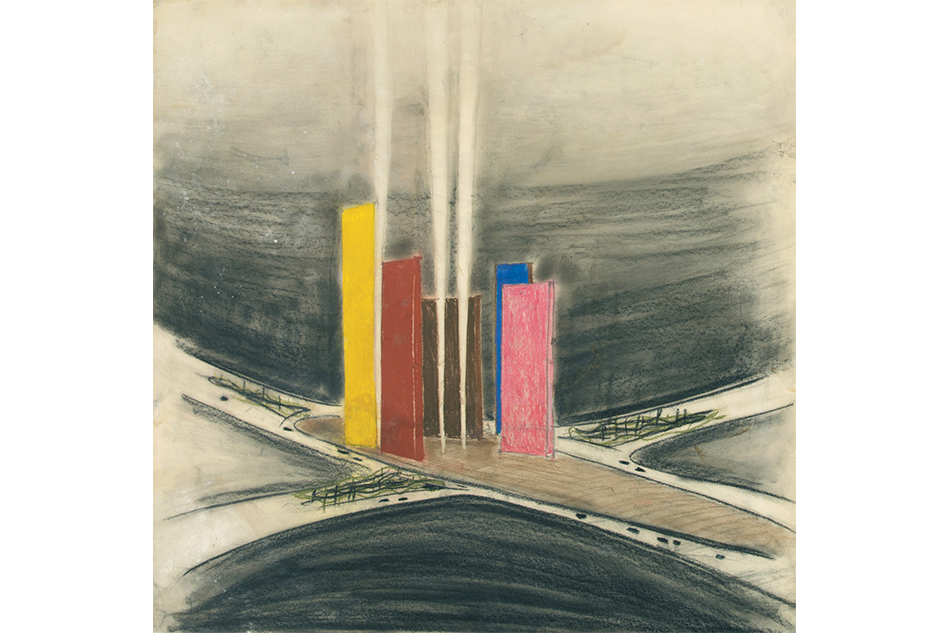

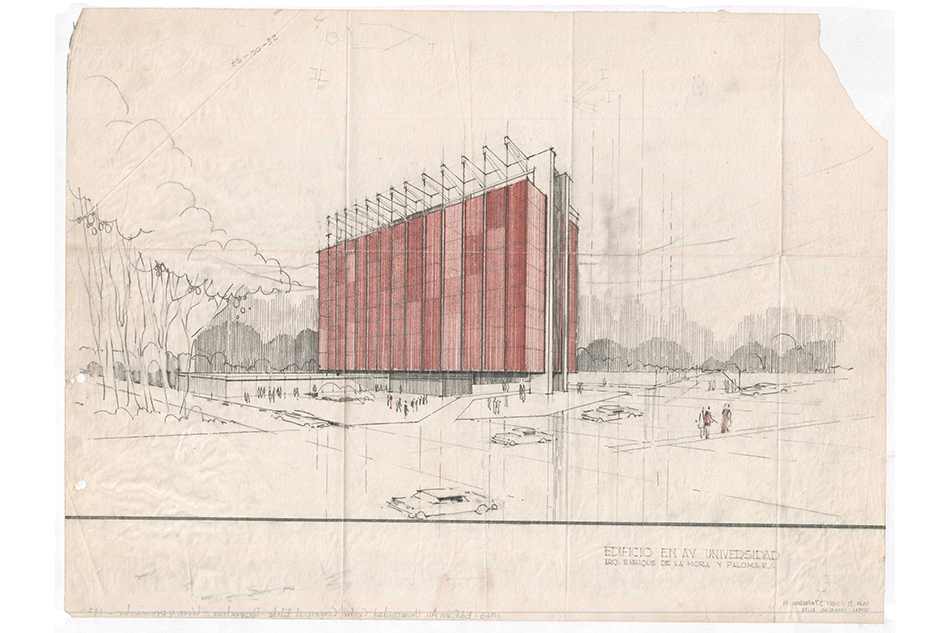

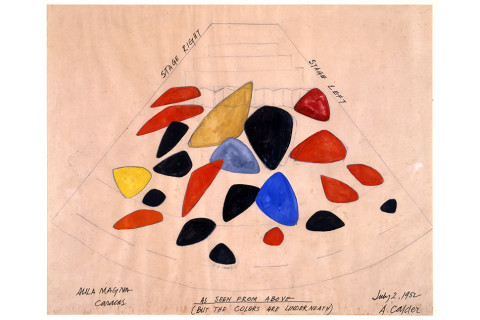

Take the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) campus, 1954, remarkable for both its crisply geometric site plan and the Aztec-inspired murals covering some of its buildings in riotous color. Color was important in Latin American architecture, at a time when “orthodox” modernism was all about pure, unadorned form. Naturally, there are works by Luis Barragan, who made pastel surfaces his trademark (one standout is his Torres de Satélite, 1957, a bouquet of towers in Naucalpan, Mexico). But there are also examples by lesser-knowns — such as the 1940 studio for Chilean architect Juan Borchers, designed by Borchers himself along with Chilean Isidro Suarez and Spaniard Jesus Bermejo, which resembled a Corbusian villa as painted by Henri Matisse.

True, there is plenty of all-white architecture: An entire room is devoted to Brasilia, the 1960 poured-in-place capital city of Brazil, whose identical governmental buildings lined up like dominoes. But the city is also home to some fascinating structures — among them the more eccentric buildings by Oscar Niemeyer, who said that Brazil’s mountains, sinuous rivers and curvaceous women inspired his designs.

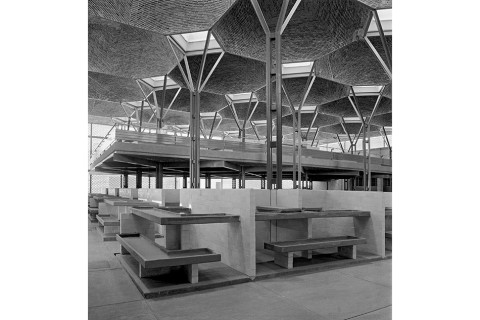

There are just a few women included in the show; the most prominent is Lina Bo Bardi, the Italian-Argentinian architect who has become something of a cult hero despite her small number of realized buildings. Bo Bardi’s own home, from 1951, which some say is her masterpiece, is hardly seen here. (If there is one drawback to the show, it is the paucity of private homes, which are relegated to a small room, painted yellow as if to suggest cheery domesticity.) She is, however, represented by images of her public projects, which included a commercial center and a cooperative beach community in Camurupim, Brazil, as well as a model of her Museum of Art of São Paolo, a gallery building suspended from vast, bright-red steel beams. The point of the supersized beams was to reserve the plaza below for gatherings and performances — even, Bo Bardi liked to say, a circus.

The show ends with a section on Latin America’s architectural exports — buildings in the U.S. and Europe designed by Latin American architects. But there weren’t many, and some of the best were temporary pavilions for world’s fairs and trade shows. The Export section merges into a room devoted to utopian designs, like those of the Argentinian architect Amancio Williams for a city in Antarctica and a sinuous, single-building metropolis.

All architects — no matter where they’re from — are trying, in one way or another, to create utopias. MoMA, with its blockbuster of an architecture show, demonstrates that hundreds of Latin American architects made significant and original contributions to that effort.

SEVEN STARS OF THE SHOW