June 15, 2025Mona Kuhn remembers the sun. Not the hazy, subtropical light of her native São Paulo nor the crisp, golden rays she’s come to work with in Southern California, but the rare, fleeting kind that sometimes emerged during childhood summers in Bad Homburg, Germany, where her grandparents lived.

“Even though it was summertime, in Germany you still had overcast weather,” she says. “But once in a while, whenever the sun would come out — this is very typical of northern European cultures — my grandparents would run to the backyard and immediately undress.”

The aging couple would lounge nude with newspapers and magazines in hand, taking in the sunlight as medicine. “They would look back into the house to my sister and me and say, ‘Mona! Julia! What is taking you so long? Undress and come out to the garden immediately. It’s vitamin D!’ ”

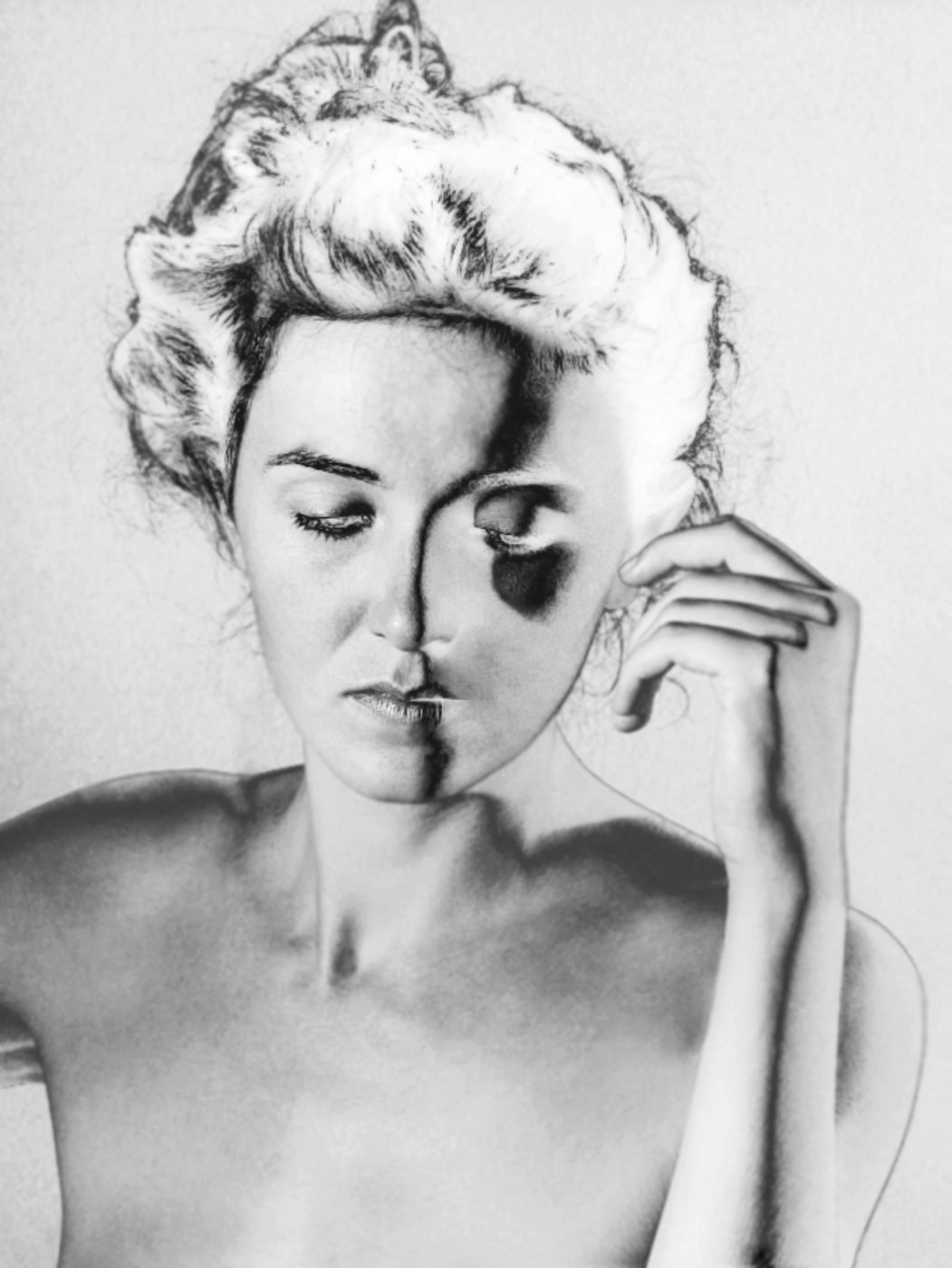

That comfort with the external human anatomy — not as spectacle but as natural presence — would become the backbone of Kuhn’s photographic explorations of the human form.

Born in Brazil in 1969 to German parents, Kuhn moved to the United States in 1989 to study photography, first at the Ohio State University, then at the San Francisco Art Institute. She dove into black-and-white photography as a language of intimacy, experimenting with angles and focus. Later, a residency at the Getty Research Institute, in Los Angeles, deepened her fascination with in the metaphysical aspects of the medium.

“Eventually, I became more interested in what the image omits,” she says. “Using photography not to document but to invite contemplation.”

Kuhn may be known as a photographer of nudes, but her vision has long reached beyond figuration. One of her latest projects, “Kings Road: A Rudolph Schindler House,” is both a tribute and a ghostly love story.

Shot inside L.A.’s Schindler House, an early modernist landmark built in 1922 by Austrian-born architect Rudolph Schindler, the series recasts construction materials as flesh and physical space as memory. “The house felt like a living body,” Kuhn says. “The raw redwood beams were like veins. The concrete reminded me of creased skin.”

For Kuhn, the Schindler House — about a 15-minute walk from her home in the Hollywood Hills — is less subject than collaborator. She pored over the architect’s archives, finding a poetic breakup letter from Schindler to a mysterious lover. Kuhn took it upon herself to metaphorically reunite the two lost souls, bringing an ethereal figure into the building’s Japanese-inspired interiors.

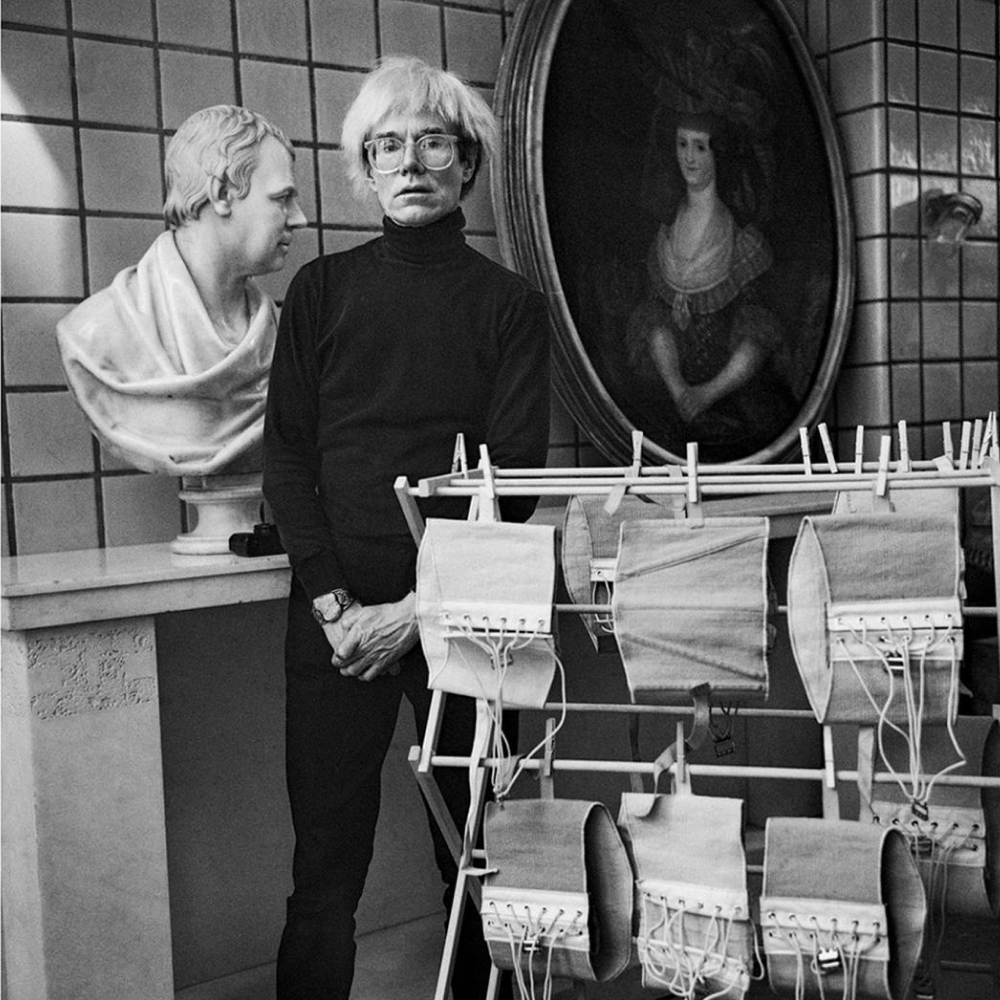

Using the early-20th-century Surrealist technique of solarization on several of the photographs, she distorted the paper’s silver tones in the darkroom until parts of her subject dissolved into shadow or light. (Man Ray popularized the effect around the time Schindler created his house.) “Each print is a unique object,” Kuhn says. “The solarization creates an unpredictability that mirrors memory itself.”

The series, which has grown to encompass sound and video art as well as photos, is on view now through December 30 at the Lianzhou Museum of Photography, in China. A new iteration of the multimedia display will appear during Palm Springs’ Modernism Week in October, and Kuhn is preparing for a wave of other solo shows: at the Leica Gallery in Los Angeles (opening September 3), the Museum of Contemporary Art in Malaga, Spain (starting September 6), and the Bildhalle in Zurich (later this fall).

While “Kings Road” is her most architecturally explicit work, its conceptual roots stretch back to the series “She Disappeared into Complete Silence,” shot in 2013–14 in a golden modernist glass structure outside Joshua Tree National Park.

There, Kuhn played with reflection, light and spatial ambiguity, creating images that fuse the desert landscape with glimpses of a solitary human form.

“The structure became an extension of the camera,” she explains. “With all the mirrors and the glass, we weren’t sure what was reflection and what was real. It created this beautiful disorientation.”

A female figure — Kuhn’s longtime collaborator and friend, Jacintha — appears suspended between dimensions, wavering between presence and absence. “It was a philosophical journey,” Kuhn says. “When you’re alone in the desert, you start to think about the universe outside and within you.”

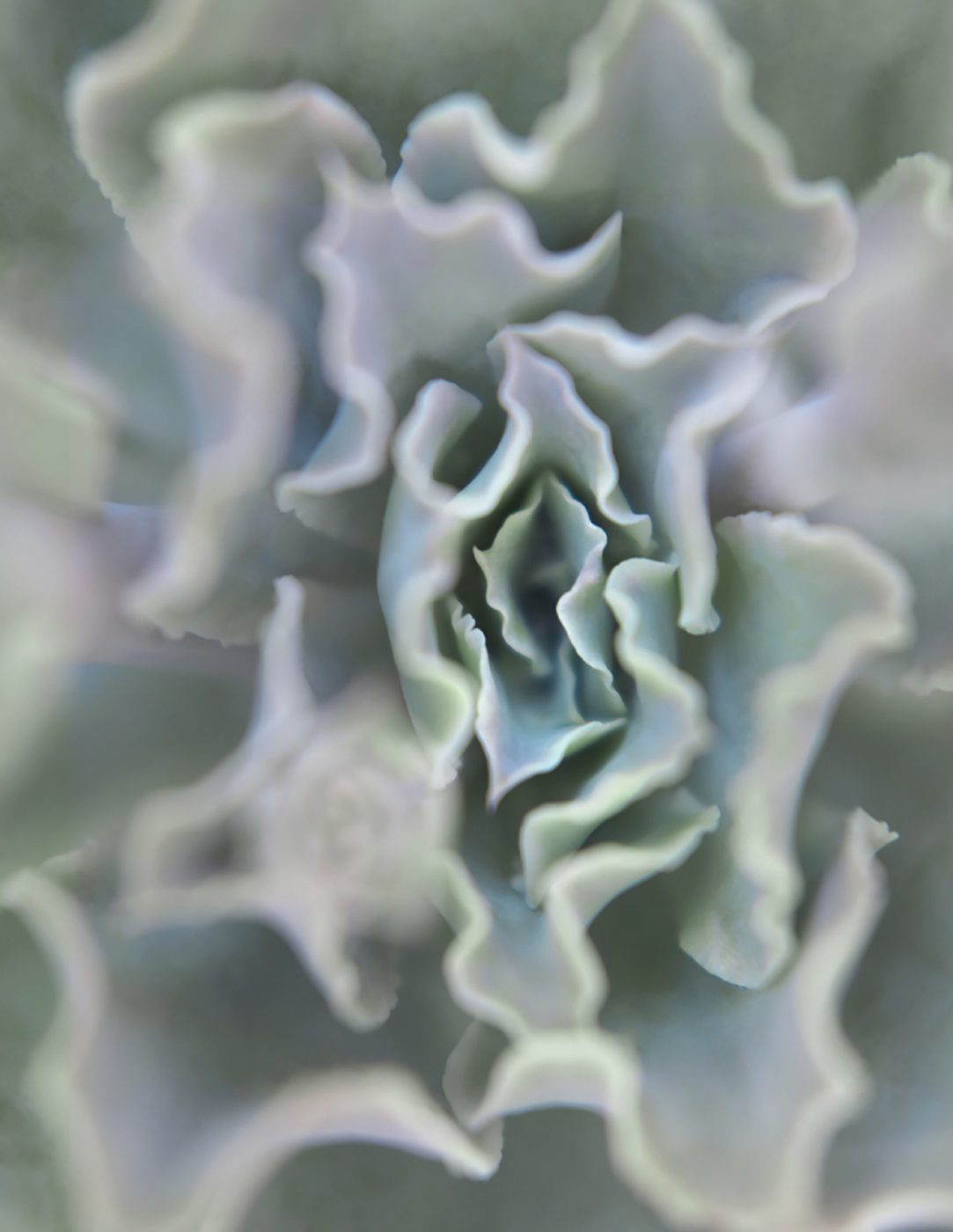

Such transcendental tendencies are manifested throughout Kuhn’s oeuvre. In “Bushes and Succulents” (2018), she turned to nature as metaphor, using sensual plant parts as proxies for the body. Inspired by Georgia O’Keeffe and Lee Miller, the series is a study in abstraction, texture and erotic ambiguity.

Still, for all her conceptual rigor, Kuhn remains grounded in her materials. She works with a medium-format Hasselblad camera, drawn to its tonal range. She often prints at large scale, favoring immersiveness and vivid detail.

Her partnership with the San Francisco gallery Edition EKTAlux has allowed her to push perceptual boundaries. “The gallery understood that I wanted the work to feel intimate and monumental at the same time,” Kuhn says. “Not just prints but objects.”

“Mona’s intimate studies of light, shapes and elusive portraiture seem to captivate collectors on a rather emotive level,” adds EKTAlux founder Julia Spiess. “Her photographs often leave room for the imagination, inspiring an almost lyrical connection.”

Recently, Kuhn has expanded her practice into video and sound, working with composer Boris Salchow to develop an accompaniment to “Kings Road.” She discovered that a soundtrack affected viewers’ pace, as they instinctively synced their bodies to the tempo.

“People unconsciously adjusted their steps to the music,” the photographer recalls. “It changed the way they moved through the work.”

Whatever direction Kuhn’s art-making takes next, “the body remains central,” she says. “And there’s always something persistent beneath the surface — a visible soul.”