July 28, 2019The name N.C. Wyeth — for those who know it — evokes the colorful, striking illustrations he created for early-20th-century editions of such beloved children’s classics as Treasure Island, Kidnapped, Robin Hood, Robinson Crusoe and The Yearling. N.C. Wyeth (1882–1945) is also known for being the father of Andrew Wyeth, who painted the iconic Christina’s World, and grandfather of contemporary artist Jamie Wyeth.

Mounted by the Brandywine River Museum of Art, in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and the Portland Museum of Art (PMA), in Portland, Maine, “N.C. Wyeth: New Perspectives” takes a fresh look at the early-20th-century American illustrator and artist. The show — in Chadds Ford through September 15 and at PMA during the fall — includes Self-portrait in Top Hat and Cape, ca. 1927 (above), and Bright and Fair, 1936 (top), which depicts the artist’s own house in Port Clyde, Maine.

A powerful recently opened exhibition, “N.C. Wyeth: New Perspectives,” proves just how much else about the artist we don’t know — and why his mythic depictions of the Wild West had a huge impact on Bruno Delbonnel, the cinematographer who work with the Coen brothers. Similarly, his illustrations of knights, pirates and cowboys influenced the likes of Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas.

The show reveals the artist in all his complexity, both personal and professional. Through more than 70 paintings and drawings, it tracks Wyeth’s career chronologically over five decades, beginning with his illustration and advertising work between 1903-1910 and moving on to his mural commissions and fine art (self-portraits, landscapes and figural works) in the 1920s until his death in 1945.

The exhibition was co-organized by the Brandywine River Museum of Art, in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and the Portland Museum of Art (PMA), in Portland, Maine — fittingly, because Wyeth divided his time between the two states. It opened last month in Chadds Ford, the site of Wyeth’s studio, now owned by the museum. Designated a National Historic Landmark, the studio remains much as the artist left it when he died and is well worth a visit.

Nightfall, 1945, captures the pastoral quality of Wyeth’s life in Chadds Ford, to which he moved with his family in 1908.

“N.C. is in the DNA of this institution,” says Thomas Padon, director of The Brandywine River Museum of Art. “He fell in love with the area and put down roots that nourished a family of extraordinary creativity for over a century.” Organizers at both the Brandywine and the PMA mounted the show because they thought it was time to reexamine the breadth of Wyeth’s career. It remains in Chadds Ford through September 15, then travels to the PMA in October and to the Taft Museum of Art, in Cincinnati, in 2020.

The eldest of four sons of a hay inspector in Needham, Massachusetts, Newell Convers Wyeth began to draw at a young age and, against his father’s protestations, attended the Mechanic Arts High School in Boston, where he learned draftsmanship.

Wyeth had an early interest in equine anatomy and hung around the Dedham Country and Polo Club drawing horses. In 1899, he began classes at the Massachusetts Normal Art School. He left to apprentice with local artists and in 1902 secured one of 12 places in the Wilmington, Delaware–based Howard Pyle School of Illustration Art. Pyle was then perhaps the most famous illustrator in America, with a network of close contacts in the publishing world. Almost at once, Wyeth became his star student. The young man was emboldened enough to send an oil painting of a bucking bronco, on spec, to the Saturday Evening Post in 1903.

It landed on the cover. Wyeth was 21 years old.

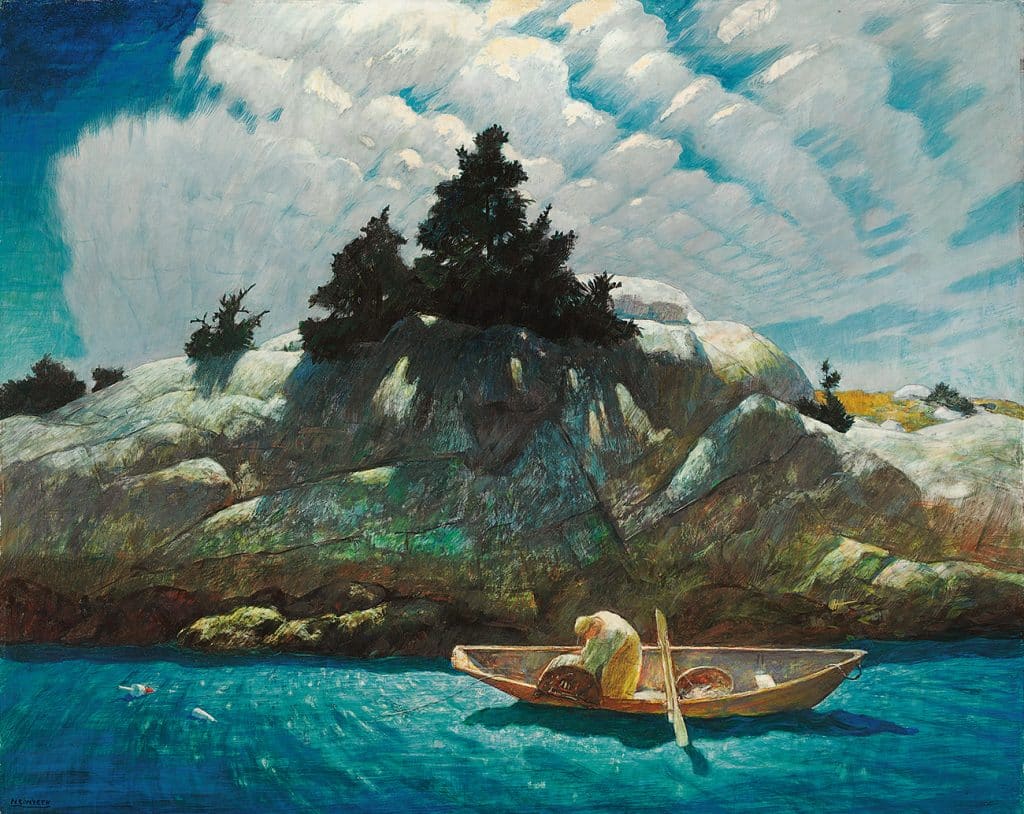

Island Funeral, 1939, was done in egg tempera, a medium that Wyeth started using after purchasing a summer house in Maine. Quick drying, it gives his Maine paintings an immediacy not seen in his oil works.

Pyle believed in first-hand experience with subject matter and encouraged Wyeth to go out West, which he did in 1904. Publisher Charles Scribner’s Sons paid for the three-month trip in exchange for right of first refusal on whatever he painted. Wyeth spent his time drawing (and working) on a ranch in Colorado and visiting Navajo lands in Arizona and New Mexico. He bought a complete Western outfit and sent home props to paint, including a birch-bark canoe, Native American pottery and beaded clothing, Western saddles, antique rifles and a buffalo head.

The exhibition includes more than a dozen of Wyeth’s Western- and Native American–themed works. One such work is a catalogue essay that looks at his contributions to the visual mythology of the American West. In a Q&A, which appears in the museum member magazine, Catalyst, Christine B. Podmaniczky, co-curator of the exhibition (along with the PMA’s Jessica May), points out that the Coen Brothers’ movie The Ballad of Buster Scruggs explicitly borrows composition, lighting and costuming from the artist’s Western painting. She also notes that filmmaker George Lucas was inspired by Wyeth’s action paintings — several from Lucas’s own collection will be displayed in the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, projected to open in 2022.

Fame came quickly and easily to Wyeth; he was a fine draftsman, great colorist and master of creating dramatic, suspenseful scenes. With Pyle’s help, his work was soon published in books and the most widely circulated magazines. He had begun a lucrative career as an illustrator.

By 1908, Wyeth had married his wife, Carolyn, and moved to Chadds Ford. By 1917, they had five children, Andrew being the youngest.

Bucking Bronco, 1903, appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. Wyeth had sent the painting, completed while he was still a student, to the magazine on spec. He was just 21 at the time.

Wyeth loved the country — there are several paintings of the bucolic surroundings of Chadds Ford in the show — and his family. A devoted father, he dedicated as much time to the artistic education of his two daughters, Henriette and Carolyn, as he did to that of Andrew, all of whom became accomplished representational painters. (His son Nathaniel became a mechanical engineer and inventor and his third daughter, Ann, became a composer and concert pianist.)

But he grew frustrated with his professional life. “He was of two minds about being an illustrator,” Jessica May writes in the catalogue. He “regretted — bitterly, at times — the subordinate place of illustration within the hierarchy of American art. Despite his fitful efforts to break free from the velvet handcuffs of his successful and remunerative career as an illustrator, Wyeth’s forays into the separate but parallel realm of modern painting were met with devastatingly mixed success.”

In 1907, Wyeth submitted a painting for the annual exhibition organized by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and it was rejected. “He wanted to be like Winslow Homer, who also started out as an illustrator, but N.C. struggled with how to break the barrier,” Padon says. Art-world critics, of course, were then focusing on modernity: Postimpressionism, fauvism, the Ashcan School, Cubism and, later, abstract expressionism. “He began to regularly turn down exhibition opportunities in galleries and other venues because he felt unprepared, unworthy or inadequate,” curator May writes. This, she continues, “amounted to near self-sabotage.”

One revelation of the show is the great variety of themes and genres Wyeth tackled: the American Revolution, the Civil War, World War I, ranching, self-portraits, still lifes, landscapes and seascapes.

Another egg tempera painting completed in Maine, Dark Harbor Fishermen, 1943, is a re-creation of an earlier oil work, Herring!, from 1935.

In one 1930 painting, In a Dream I Meet George Washington, Wyeth paints himself, seen from the back, in contemporary clothing, standing on a scaffold, palette and brushes in hand. He’s talking to Washington, who is on horseback leading his troops to battle in the valley where the actual Battle of Brandywine took place. There are dead redcoats on the ground. General Lafayette waves his hat from the distance. And Wyeth’s son Andrew is seen in one corner with his dog, sketching the entire scene, including trees resplendent with bright autumn leaves. It is an amazing, vibrant painting.

In 1920, Wyeth bought a summer house in Port Clyde, Maine, avid to capture, as he wrote, “the loftiness, the majesty, the sublimity of that wonderful shore.” My family had a summer house there, too, and for me, the easel paintings Wyeth made of the coast are his strongest and most moving works, especially Island Funeral, which he did in what was for him a new medium: egg tempera, a mixture of pigment, water and egg yolk. (Andrew subsequently adopted it, with legendary success.) The use of tempera, which dries very quickly, gives these Maine paintings an immediacy not seen in the oils.

Wyeth’s 1930 In a Dream I Met George Washington, imagines the artist encountering the American hero in the valley where the actual Battle of Brandywine took place.

For his tempera, Wyeth employed pigments provided by chemists at the DuPont laboratory, who made them from the company’s new, super-vibrant synthetic dyes. As curator Podmaniczky writes in the catalogue, “The rich, opalescent and light-fast blues and greens Wyeth used in Island Funeral derived from cutting-edge research driven by science and industry — better art through chemistry, indeed.”

These paintings were in the artist’s first solo exhibition, at the Macbeth Gallery, in New York, in 1939. The show was not nearly as successful as he had hoped it would be, leading to a bout of depression. “All I can do . . . is to gawk stupidly at the retreating pageant of my dreams and hopes,” he wrote to his daughter Henriette in 1941. “I am working furiously; that is my one salvation. I wonder how long I’ll be allowed that.”

He died four years later and was soon overlooked, as Andrew stole the limelight. “N.C. Wyeth: New Perspectives” should change that.