April 6, 2015The Cuban-born, Washington, D.C.-based Nestor Santa-Cruz is a design director at the international architecture and design giant Gensler as well as a residential interior designer at his own eponymous firm. Photo by Angie Seckinger

Jean Cocteau once wrote a beautiful adieu letter to another notable Jean, his friend Jean-Michel Frank, who ended his own life in New York in March of 1941 at the age of 46. “His death was the prologue of the drama, the final curtain rundown between a world of light and a world of darkness,” wrote Cocteau in Art et Industrie in 1945.

Indeed, it is the very lightness of Frank’s interiors and furniture that has influenced so many decorators, including me. One of the most important designers of the 20th century, Frank enjoyed a relatively brief yet impactful career from the early 1920s up until his death, during which he created poetic spaces where simplicity and proportion are the key elements. This past February marked the 120th anniversary of his birth, and as I write these reflections on his influence, I cannot imagine what my own design sensibilities would be had I not studied his work.

In the early 1970s, long before I enrolled in architecture school in the United States, I encountered Frank’s interiors in the pages of a few old design magazines at the library of the Alliance Française in San Salvador, El Salvador, where I was raised. (I was born in Cuba, but owing to my father’s job with IBM, my family lived throughout Central and South America in the 1960s and ’70s.) By the time I turned 15, I was already interested in architecture and interiors, and the magazines of the Alliance Française’s library were the best education in chic. I also distinctly remember an essay by Van Day Truex, at that time the design director of Tiffany & Co., in the September/October 1976 issue of Architectural Digest, in which Truex discussed Frank’s enduring importance in the history of interior decor and how the designer’s close association with art patrons was unique to the Paris scene in the 1930s. Poring over these publications, I began to grasp the strength of Frank’s less-is-more approach.

The French designer in 1935; the 1930s proved a pivotal decade for Frank, as it was then that he established his own boutique and began designing for the beau monde of his day. Photo by Rogi André, courtesy of Comité Jean-Michel Frank

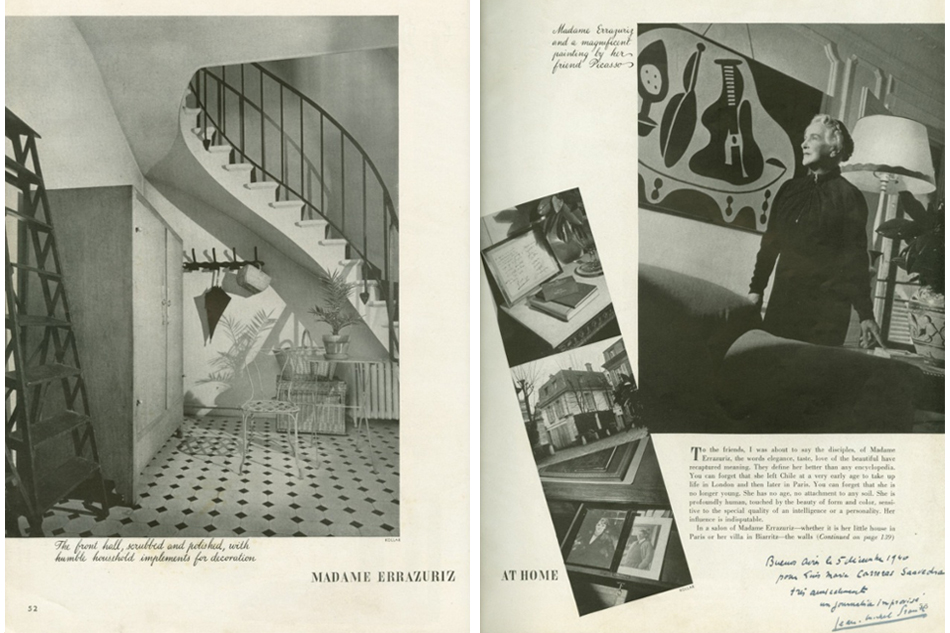

Though he was glamorous in appearance, Frank’s life was marked by tragedy. Born in Paris at the turn of the last century, he was a lonely and quiet child who attended the city’s prestigious Janson de Sailly school. Classmates bullied him for his delicate, puppet-like appearance and his Jewish heritage. (Anne Frank was his first cousin once removed.) He lost his two older brothers in World War I, and, not long after, his father committed suicide, and his mother died in a Swiss asylum. Despite these calamities, and thanks, in part, to a hefty inheritance, Frank eventually found a niche within the the Roaring Twenties’ smart set — intellectuals, politicians and artists — traveling the world extensively and eventually encountering his decorating mentor, Eugenia Errázuriz. A rich Chilean friend and mécène of Picasso, she imparted to Frank what would become a guiding principal of his work: “Elegance is elimination.”

In 1930, after working on his own Saint-Germain-des-Prés apartment and other important early commissions, he partnered with the cabinet-maker Adolphe Chanaux, who had trained with Art Deco master-designer André Groult. They opened the Jean-Michel Frank boutique at 140 rue de Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Rapidly, Frank became the go-to designer for haute society members of the time: Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Gaston Bergery, Elsa Schiaparelli, Jean-Pierre Guerlain, Count and Countess Pecci-Blunt and the arts patrons Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, all in Paris; the Union Pacific Railroad heir Templeton Crocker in San Francisco; the Rockefellers in New York; and the wealthy Born family in Argentina, among others.

“As I write these reflections on Frank’s influence, I cannot imagine what my own design sensibilities would be had I not studied his work.”

“A husband-and-wife duo wanted a minimal yet comfortable approach,” says Santa-Cruz of a home in the Belle Haven area of Alexandria, Virginia. “I gave them a monograph on Frank. Overnight, they bought in to my desire for a conscious interpretation of Frank’s ‘less is more’ version of spareness.” Photo by Angie Seckinger

As per Errázuriz, Frank’s rooms were devoid of the unnecessary. It could be said that the emptying of the room was Frank’s raison d’être. Luxury was in the quality and not the quantity of the furnishings. Antiques displayed the best craftsmanship. The furniture designs by his own hand, or by someone in his artistic group (Salvador Dalí, Alberto and Diego Giacometti, Emilio Terry and Christian Bérard), were quasi-tribal in style — exotic woods with Cubist lines, executed in pure, classical proportions. The level of quality was comparable to the work produced by the great French ébénistes, for whom perfection was the only acceptable result. Color was either absent or shocking. For materials, Frank turned to shagreen, parchment, mica, straw marquetry, plaster, raw silk, Hermès leather, wicker and forged iron.

Today, more than 30 years after my initiation, I am still guided by Frank’s constant influence, and I am not alone. The Paris-based Jacques Grange creates the most contemporary of chic spaces embodying the Frank spirit, and, in a similar vein, the refined American interiors of Stephen Sills demonstrate the importance of scale in furniture, as well as the necessity of rigor when selecting unusual decorative objects. Architect Peter Marino, for his part, practices design with a similarly sophisticated use of materials, and his collaborations with today’s great artists recall Frank’s partnerships in the 1930s.

In my own work, I am always in search of Frank’s design harmony. Regardless of the style in which I am working, or the type of space at hand, I want to preach design restraint to my clients like a religion. Luckily, I have found a few converts.

“The original 1940s faux–painted-oak paneling of this neoclassical library in Washington’s Forest Hills area provided the perfect architectural envelope,” says the designer. “My solution was to introduce furniture and elements reminiscent of Frank, imitating his tailored and serene approach to traditional rooms.” Photo by Angie Seckinger

Recently, working on the Washington, D.C. home of my German-born friend Sabine Curto and her lawyer husband, Michael, I created a dining room as an homage to Frank. Ivory-colored wallpaper squares mimic his favorite parchment-covered walls, Thai raw-silk draperies softly frame windows, and solid, scraped white-oak furniture is juxtaposed with an original Frank table in verre églomisé and black iron.

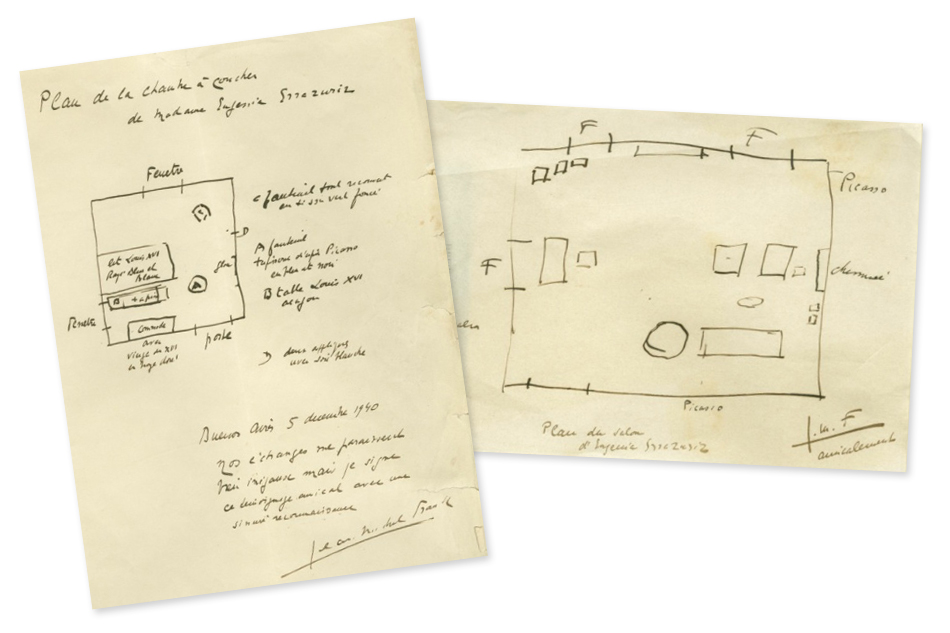

On my frequent visits to Paris, I always pass Frank’s former apartment building at 7 rue de Verneuil, in the 6th arrondissement, on my way to visit Willy Rizzo’s design gallery across the street. I look up and wonder what it must have been like in his inner sanctum. A few years ago, I bought two rare sketches by Frank’s own hand from an antiquarian-book dealer in Buenos Aires. Every time I look at these images — which depict the layouts of the salon and bedroom of Madame Errázuriz, and now hang in my own living room — I marvel at the ability of this most elegant of personalities, so full of internal sadness, and how he learned to create beauty out of the void.

Laurence Benaïm, the famous French writer who is now working on a biography of the designer for Éditions Grasset, recently told me, “Frank will continue to haunt our memories. Through his creations, he showed us the modernity of a point of view, impossible to reduce to a fashion or style. His force is to have opposed any form of theory or message — the ultimate truth of a dateless taste.”

I read once that Cocteau, while leaving Frank’s apartment for the first time, said, jokingly: “Pity, the burglars got everything.”

I beg to disagree.