May 7, 2023As a magazine journalist, editor and creative director, Christopher Tennant has always been intrigued by the totemic power and romance of vintage objects and ephemera. “I’m fascinated by cultural artifacts and have collected a few over the years,” says the 44-year-old former Vanity Fair contributing editor and author of The Official Filthy Rich Handbook. “John and Yoko’s Christmas cards, Studio 54 drink tickets, Black Panther Party newspapers.”

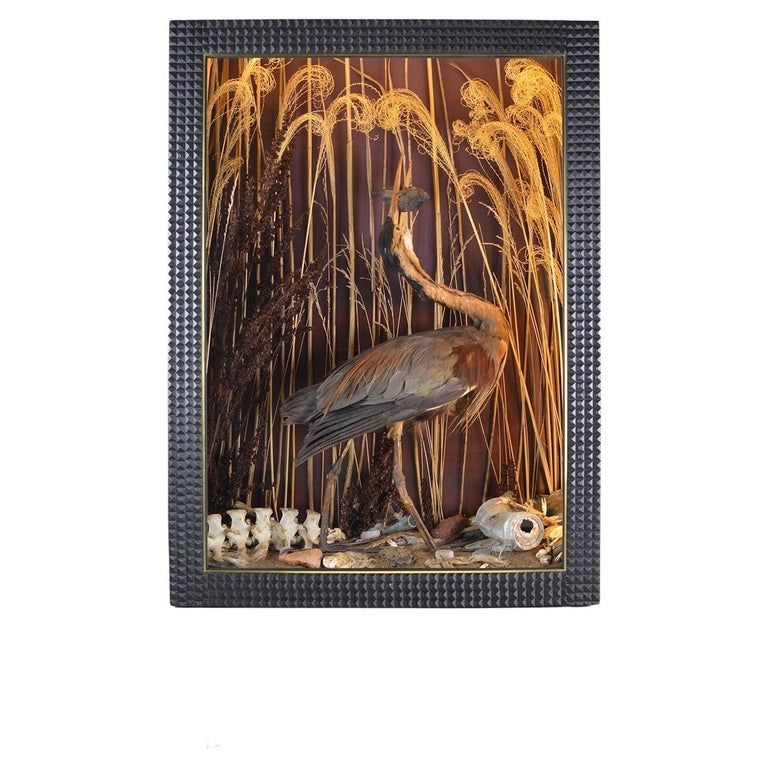

In 2011, Tennant, who also admits to being an obsessive collector of rocks, butterflies and Victorian taxidermy, began crafting illuminated cases — dramatic dioramas that tell stories through light and paint and the positioning of objects, such as his 2022 Wetland, featuring a purple heron surrounded by sand, reeds, grasses and beach detritus.

“Along the way, I learned taxidermy repair, carpentry, wiring and glass cutting by making every mistake you could,” he says, laughing. “Now, I am quite handy.”

His earliest vitrines caught the attention of art collectors and interior designers, including Nina Freudenberger, who told Tennant she’d need 10 to put together his very first show, which opened at her New York City store, Haus Interior, over a decade ago. He has since worked with other creatives, like the architect Mark Zeff and Stefan Beckman, who designs sets for Tom Ford.

During the pandemic, Tennant had a lightbulb moment about his artistic calling. In 2020, he had bought a 1920s California-bungalow-style house in Brookhaven, Long Island, built by society architect Bradley Delehanty for Vogue editor Edna Woolman Chase. “I spent lockdown figuring out the house,” he says. “We needed to fill a spot in the ceiling, and I had seen a tatty old house in the English countryside in an old magazine that had a couple of paper parasols for light fixtures.”

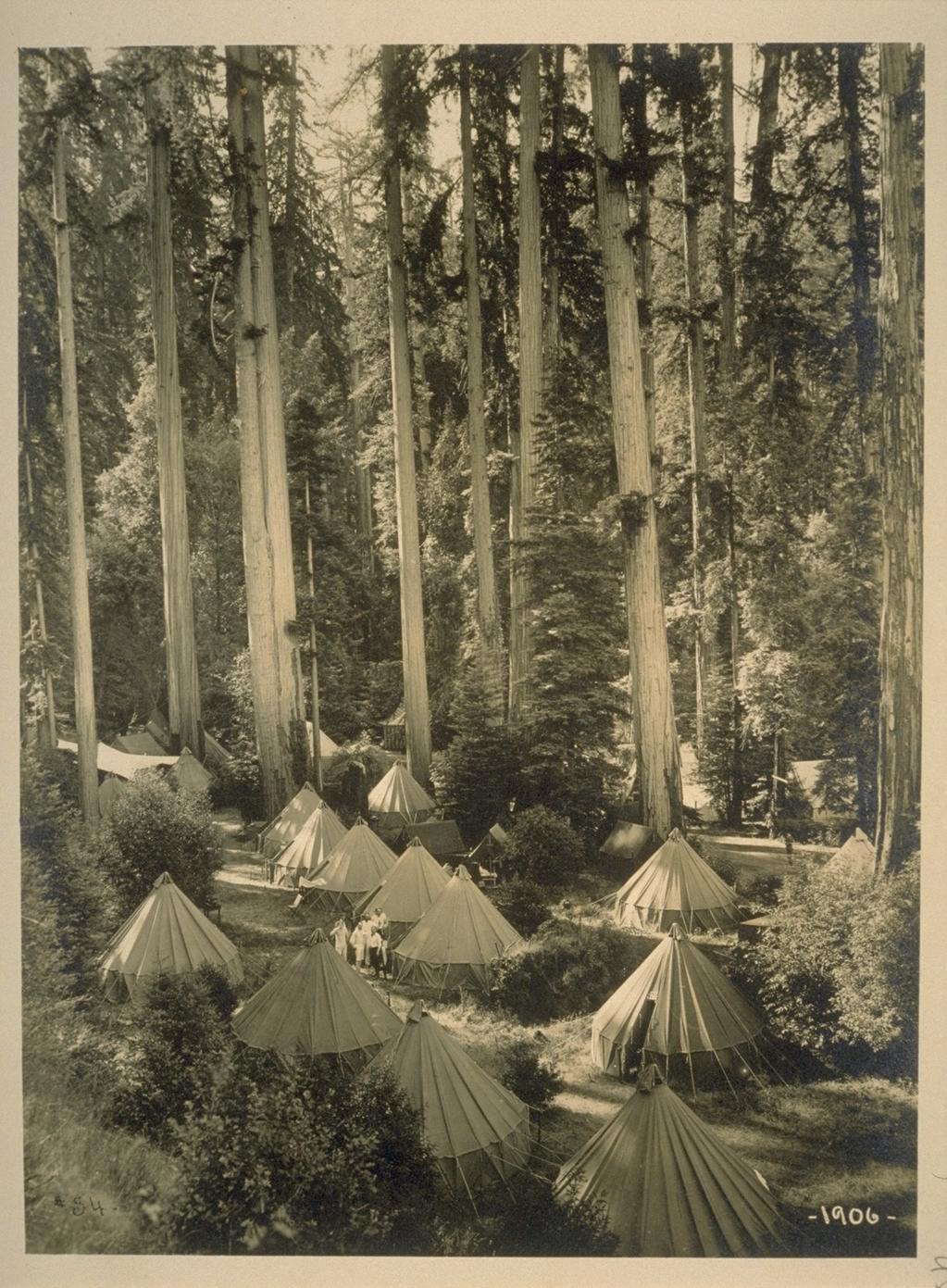

After hanging similar fixtures in his own home, Tennant wondered whether parasols would also look good as shades on top of poles made from bamboo, which grew abundantly in his backyard. Taking cues from such lighting designers as Paavo Tynell and Carl Auböck, he created the 2022 World’s Fair Collection, a colorful array of table and floor lamps with bamboo poles, bases of coconut shell or coiled seagrass and shades fashioned from dazzling souvenir parasols from the Japanese pavilions of the 1933, 1962 and 1964 World’s Fairs.

Tennant’s Horst collection, an homage to the legendary fashion and celebrity photographer Horst P. Horst, pairs baskets and Vietnamese non la field hats, woven to look like the hides of scaly anteaters known as pangolins, with vintage German-made camera tripods. For his 2022 show at the Vanderbilt Museum, on Long Island’s North Shore, he referenced the “insanely cool” sculpture and furniture of Salvador Dalí. The resulting Vanderbilt collection features an 80-inch bamboo lamp decorated with a jumbo taxidermy lobster.

“It marries the two disciplines: lighting and natural history,” he explains. “And I have always been obsessed with giant examples of natural things.”

Introspective recently spoke with Tennant about his pivot from journalism to handmade lamps, sustainable design and finding inspiration in the basement of a mansion.

Illuminate us: Why did you decide to become a couture lamp maker?

During COVID, as the magazine industry increasingly became a pale shadow of itself, I was looking to make something reproducible. Everyone doesn’t need an illuminated Victorian taxidermy vitrine, but everyone needs a lamp. They are movable, expressive and have the power to change a room.

How do you develop your designs?

I don’t draw things out. I play, test and stand back, like dressing a mannequin. I work with as many found vintage pieces and antiques as new parts and also use natural materials, like paper and seagrass, that add texture in a refined and elegant way. Where the handmade and machine-made meet is where beauty lies. Things that are too perfect bum me out.

Your lamps have so much personality. Can you play decorator and pair them with other designs?

With the Horst collection, the proportions of the tripods would play well with a Barcelona chair and a Ward Bennett I Beam side table. The World’s Fair lamps could sit in a corner next to a de Sede non stop sofa, and the Jumbo Lobster lamp should be in a place with no kids, even though the lobster is detachable — I say this as the father of a seven-year-old. The illuminated cases look spectacular above a mantel and even better built into a nook, so they’re flush with the wall.

Where do you go for creative motivation?

The American Museum of Natural History, in New York, has always fascinated me. To see life depicted like that triggers something in our primitive brains. Last year, I had a show at the Vanderbilt Museum, on Long Island. William K. Vanderbilt was a Gilded Age tycoon and collector of natural history. I had been to the Vanderbilt mansion once with my mother-in-law. I was dragged around, but in the basement was the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen: the Hall of Fishes, a Wes Anderson dreamscape with species from his travels all over the world.

What books do you keep close by?

One of my favorite books is Joseph Cornell/Marcel Duchamp…In Resonance. I’m a big fan of both Cornell and Duchamp and hadn’t been aware they knew each other. So, to discover they were close friends and there was this trove of letters, mementos and other ephemera hit the trifecta. Handmade Houses, the book about artists who treat their living spaces as artistic projects, has been a formative text for me.

Which artists have inspired you?

Paul Thek, who began his “Technological Reliquaries” series — hyperrealistic wax replicas of organic “relics,” like a Roman soldier’s sandal-clad severed foot, encased in these sleek glass and neon acrylic vitrines — in 1964. You’ll never look at Damien Hirst’s cabinet pieces, which I also love, in the same way again. Among other contemporary artists, I love Tom Sachs’s handmade, DIY approach.

Who are your design heroes?

Though I own a lot of mid-century designs, for me, the nineteen twenties and early thirties, a dynamic period of modernism and craft, remain the high point of aesthetic culture. Jean-Michel Frank, Frank Lloyd Wright, André Groult, Jean Dunand, Eileen Gray, Corbusier — we’re all in their jet stream.

I’m also drawn to organic modern designs, where the primitive and the modern meet, like Audoux Minet rope lighting; Pierre Chapo’s woodworking; Ate Van Apeldoorn’s chunky, brutalist furniture with solid pine joinery; and absolutely everything Charlotte Perriand made.