April 16, 2014New York gallerist Pavel Zoubok (top) specializes in collage across all media, including the work of Al Hansen, a founder of the Fluxus art movement, who crafted his Untitled (Street Butt Venus), 1985 (above), from the discarded ends of used cigarettes. All photos courtesy of Pavel Zoubok

In 1948, writing about a collage show at the Museum of Modern Art, Clement Greenberg dubbed the medium “the pasted paper revolution,” describing it as “the most succinct and direct clue to the aesthetic of genuinely modern art.” In 1997, nearly half a century later, the New York dealer Pavel Zoubok decided to explore this aesthetic further by opening a gallery in a salon-style loft space in New York’s Soho that’s entirely dedicated to collage.

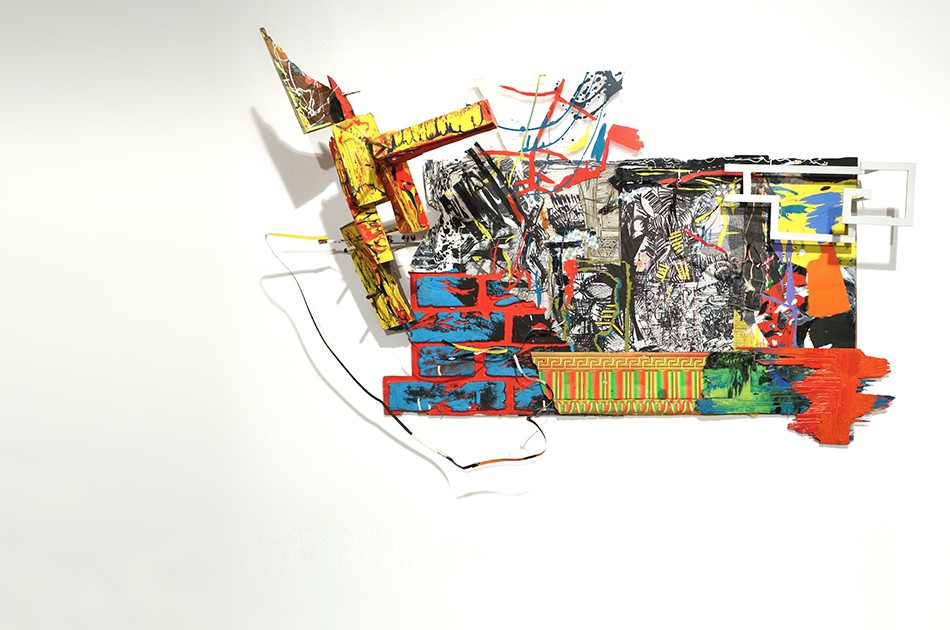

Back then, the discipline didn’t really have much of a profile in the art world. At best, it was associated with the early work of Pablo Picasso (whose 1912 Still Life With Cane Chair is generally regarded as the first collage). At worst, it was dismissed as the province of glue-gun-wielding, hearts-and-lace-pasting, obsessive-compulsive amateurs. The medium was also attached to historical movements like Dadaism and Surrealism, but because those contributions were often regarded as works-on-paper when they came to market, they weren’t taken as seriously as painting or sculpture. Zoubok, counterintuitively, had the bright idea of showcasing collage and nothing but collage: from Surrealism and Pop to Pattern & Decoration and beyond, and from paper to every other medium — thereby helping to give it a sense of gravitas and encouraging the art world to reconsider it. (The fact that his gallery’s rise dovetailed perfectly with the resurgence of interest in works on paper also helped.)

His first exhibition, in 1997, showed off the medium’s creative and historical range, with work by the British Surrealist Stella Snead, the 1980s Dadaist Buster Cleveland and the collagists Michael Langenstein and Joan Hall. When the show’s opening drew more than 400 people, Zoubok realized he was on to something. By 2001, the dealer had moved to the Upper East Side, and, since 2004, he has been in Chelsea, where he has built the careers of such artists as Mark Wagner, whose work, made from meticulously cut and pasted dollar bills, has become an Internet sensation, and Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, whose Byzantine assemblages were the subject of “Tender Love Among the Junk,” a 2012-13 retrospective at MoMA-P.S.1. “Pavel has the most knowledge and the best eye of anyone I know in the field,” says a longtime collector, Francis H. Williams. “And he has an infectious enthusiasm.”

New York artist Barton Lidicé Beneš, who died in 2012, created the mixed-media assemblage Aviarius in 2005. Zoubok now represents the artist’s estate.

Today, Zoubok represents 18 artists and nine estates, from Buster Cleveland and Addie Herder to Barton Lidicé Beneš. In 2011, he founded the International Collage Center, a nonprofit that uses its lending and research collection to promote the field. Recently, the ICC toured “Remix,” a huge survey of modern and contemporary collage that opened at Bucknell University’s Samek Art Gallery in fall 2011 and traveled to three other venues before closing at the Bates College Museum of Art, in Lewiston, Maine, last month.

The gallery’s current shows (running through April 19, 2014) focus on 25 years’ worth of collages and sculptures of faces made from found objects by the legendary graphic designer and artist Ivan Chermayeff and 1940s collages by the magical realist illustrator and artist Witold Gordon. “The wonderful thing about this specialization,” Zoubok says, “is that it allows me to be incredibly eclectic and still really focused at the same time.”

Here he talks about his love of the medium and the fluctuations of the art market while also confessing to a newfound addiction to design.

What first sparked your interest in collage?

While at Sarah Lawrence, I spent my sophomore year in England. On a visit to Cambridge, I saw a small exhibition at Kettle’s Yard of the Czech collagist and poet Jiří Kolář, who developed more than a hundred collage techniques — from “chiasmage” [using cut-up text to make an abstract pattern] to “intercollage” [inserting one image into another] — and really regarded them as a personal language. It was a revelation. I could see that a lot of my other interests, whether it was painting or fashion, in some way centered around collage. I just recognized it as a kind of philosophy. The show ended up traveling to the London Institute of Contemporary Art. I must have seen it there a hundred times. Collage became my gateway drug to art history.

The gallery also represents the estate of Addie Herder, whose collage construction New York Phoenix, 1976-77, is pictured above.

Why did you decide to establish the gallery?

I wanted to create a context for collage, one where artists who were considered very esoteric by the mainstream could play a central role. Outside of very well-known collagists like Robert Rauschenberg or James Rosenquist, the market was primarily for historical material, like Surrealism and Dada. There was no dedicated thought to collage as an area unto itself. Artists like Ray Johnson, Al Hansen and Hannelore Baron — not quite Fluxus, not quite Abstract Expressionist — they had always just floated. Even someone as beloved and central to art history as Joseph Cornell still occupies a marginal space in the art world’s grand scheme.

What was your first major sale?

A unique drawing by Marcel Duchamp, for more than $50,000 to another dealer. It was in the late 1990s, and my husband [Paul A. Baglio, Jr., a visual director for Giorgio Armani] and I were living in a tenement apartment in Chelsea. I remember being very concerned about keeping the drawing there.

How has the market changed since then?

I’ve been fortunate enough to ride the wave of interest in works on paper, as well as a more general market wave. In 2002, Al Hansen’s Hershey-wrapper collages were selling in the $8,000 to $15,000 range. Now, these things, when you can get them, sell anywhere from $35,000 to $200,000. In the old days, Mark Wagner’s works were mostly under $10,000; now they’re $18,000 to $100,000 and up. Even historical artists became more important in context. Kolář hadn’t been shown in New York since his 1975 Guggenheim retrospective, but when we showed him with Joseph Cornell in 2007, we sold out the entire show.

You can still get enormous quality at prices that are not astronomical, however. Even Cornell, who’s on the high end of the spectrum, can be quite reasonable. You can still find an okay box for a few hundred thousand dollars. You can’t even buy a scribble by most modern masters for that.

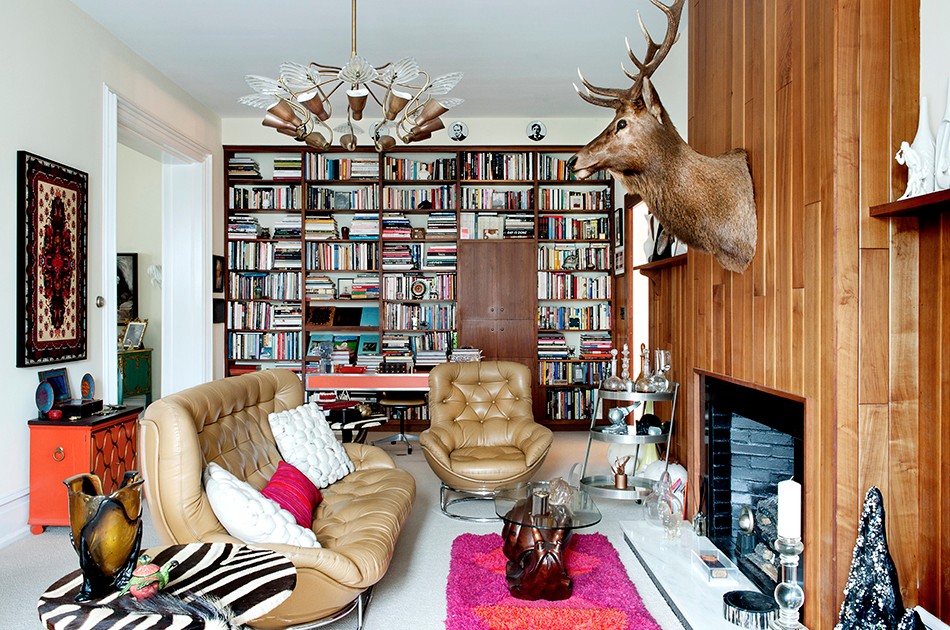

Zoubok recently started collecting vintage design for his home, including a 1940s French lamp from Kerson Gallery and a red chair from Johnson Trading Gallery, both 1stdibs dealers. Photo by Emily Andrews

I understand that you also collect design.

Five years ago, Paul and I bought a very large Victorian house in central Pennsylvania, and, while decorating it, we both developed a passion for decorative art. I, in particular, went on a veritable rampage and started all kinds of collections: antique spiders; 18th- and 19th-century French and German porcelain, particularly chinoiserie; Venetian blackamoors; vintage Fornasetti ceramics; and portraits in all media, to name just a few. For a few months, I was constantly on 1stdibs. Paul and I now have so many friendships with antique dealers, like Liz O’Brien, who taught me that I could buy a chair or a table with the same level of commitment that I would buy a picture.

After Hurricane Sandy hit Chelsea, you moved to a much larger space. Why?

We were up and running again in two weeks. But I felt emboldened to make a move. My curatorial ambitions had long outgrown my space. And, in a moment where the gallery model may soon be supplanted by art fairs and the Internet, I wanted to reaffirm my commitment to the gallery experience, to become more aggressive about curating great shows and increasing the program’s visibility. Every gallery is a community of artists, and ideas and real connoisseurship comes from having relationships with those communities.

Why has collage continued to hold your interest?

For me, it is the essence of modern and contemporary life, manifested in the digital culture that is transforming our society. That culture is hybrid by its very nature: Facebook, Photoshop, Twitter, 3-D printers. All these things utilize layering and cut-and-paste, both in terms of imagery and thinking. And, for me personally, it is the language I speak in, the language I think in, the language I decorate in, the language I collect in. When I’m describing the ICC, I often use the line, “from Picasso to Facebook.”