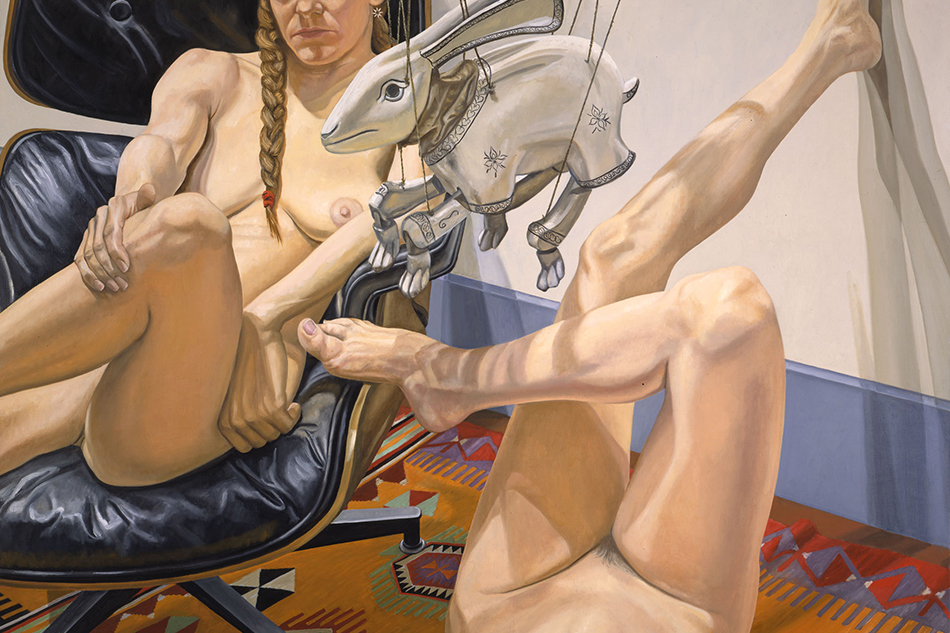

February 27, 2013New York–based contemporary painter Philip Pearlstein, a master of the female nude, is also a collector of all kinds of ephemera. All images courtesy Betty Cuningham Gallery and the artist; Top: Model on Wooden Lounge with Swan, 2013

Philip Pearlstein’s name may be synonymous with the contemporary nude, but it’s his vast collection of objects, culled over more than half a century, that seems to give him the biggest thrill. The artist lives and works on a full floor of an unobtrusive building in New York’s Garment District in the West 30s. He and his wife of more than 60 years, Dorothy, now make their home in its front rooms, hung with some of Pearlstein’s famed canvases — one features a creepy-cute Popeye doll peering out between a disrobed man and woman — and a wall full of classic prints by Eadweard Muybridge. Other charming pieces on display include Tiffany lamps and whimsically decorated high heels bequeathed by a shoe-designer cousin. It’s a spacious back room, however, that reveals the real cabinet of curiosities: a treasure trove of objects spanning cultures, continents and centuries.

A pair of carved mahogany lions with a Japanese flair, which purportedly once adorned Luna Park at Coney Island, guards a group of Indonesian animal puppets, and, across the way, an elegant swan sits amid a cluster of wooden duck decoys. One can see old toys, an antique American birdhouse, a carved Tibetan monkey, tiny figurines, an Ethiopian chair made from a tree trunk, Native American antiquities and a cutout of George Washington. Odd, unidentifiable pieces cover every surface; some are Etruscan, others Egyptian. Pearlstein points to one piece of unknown origin, a sculpture roughly a foot high of a female holding her breasts, her shape flattened in a primitive style. “She’s so much like Matisse, I had to have her,” he says.

Model on Eames Chair in Patchwork Kimono, 2012.

Pearlstein amassed the collection from flea markets, private dealers and auctions, and if there’s a thread connecting them, it’s that “all these cultures go together,” he says. Scores of the objects have co-starred with nude models in Pearlstein’s canvases, injecting them with elements of the modern still life. “Almost everything’s been used in paintings unless it has very religious overtones,” he explains. “With the nudes, it would offend people, and I’m not interested in making points.”

In his latest show, on view through March 30 at Chelsea’s Betty Cuningham Gallery, which has represented him for eight years, one painting, for example, depicts a nude woman with her legs draped over the swan. In another, a model reclines on a Mickey Mouse blanket. The props, he says, provide another layer of difficulty. But not insurmountable difficulty, it appears: The man is 88 and still painting, “officially three days a week,” he says with a gleam in his eye. “But then I do portraits and work on prints,” he adds.

Recently, a pleasant afternoon in February finds Pearlstein, neatly dressed in a dark brown T-shirt and jeans held up by suspenders, eating a salad during his lunch break. As he reminisces about his early days as an artist, he puts down his fork to go look for something in the adjoining studio. After wading through a stack of works awaiting packing for a solo exhibition in March at the Museum of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, Florida, he pulls out a small, framed canvas of a carousel. The brushstrokes are quick and light, capturing the speed of the horses and tigers spinning by, and the colors are bright. “It’s a total American scene painting,” Pearlstein remarks. It was also his very first oil painting, completed around 1940, when he was in 11th grade in Pittsburgh. The painting won a national competition and landed Pearlstein in the pages of Life magazine.

Al Held and Sylvia Stone, 1968

That would prove to be just his first brush with fame. Perhaps more than any other artist in the second half of the 20th century, Pearlstein made painting the human figure a viable option in contemporary art. By Pearlstein’s assessment, though, his decision to tackle the nude arrived relatively late. First came art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in his hometown, interrupted by service in World War II, during which he painted signs and the like.

When he returned to Carnegie after the war, he befriended a younger student named Andy Warhola, who would, of course, later drop the ethnically tinged “a” from his surname. “Someone pointed out later that I was probably the first person he met who was famous,” Pearlstein says. “The first time I met him, he said, ‘What’s it like being famous?’ I said, ‘It only lasted five minutes.’” (Naturally one can’t help but wonder if he inspired Warhol’s famous 15-minutes-of-fame quip.)

After graduation, the two moved to New York and became roommates. Pearlstein says Warhol’s older brothers trusted him to take care of their little sibling because they knew Pearlstein’s father from the wholesale food business in Pittsburgh. The two artists roomed together for almost a year before being evicted, and Warhol was in the wedding party when Pearlstein soon married Dorothy Cantor, another Carnegie alum. (She stopped painting shortly after her first solo show in the 1950s, a topic that, he says, “we were never allowed to discuss. Even now.” A moody Maine landscape by Dorothy does hang in the studio, however.)

“I realized my life was nice. There was nothing

to be expressionistic about anymore.”

Standing Male, Sitting Female Nudes, 1969

Pearlstein and Warhol remained friends, though their lifestyles diverged. Asked if he was ever a regular at the Factory, Warhol’s studio-cum-party palace, Pearlstein shakes his head. “Oh no. I think I visited twice.”

In the 1950s, Pearlstein fell into the category of second-generation Abstract Expressionists — “like everybody else,” he says — which he attributes in large part to the war. “I think that altered my generation,” he says. “I think the whole Abstract Expressionist movement flourished because we were using painting as a way of working out our wartime experiences. I reached the end of that when I was roughly age 37 or 38.”

At that point, having earned a Masters from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, Pearlstein was teaching at Pratt and painting at night in his Upper West Side townhouse. He was a married father of three. “I realized my life was nice,” he says. “There was nothing to be expressionistic about anymore.”

Meanwhile, he was teaching a figure-drawing class at Pratt, where the Ab Ex movement and the idea of the “gesture” so dominated that “they wanted you to scribble [the nude],” he recalls. One faculty member told him, “Nobody bothers to teach perspective anymore because nobody is using it.”

Model on Air Mattress with Mickey Mouse Blanket, 2012

“I took it as a challenge,” Pearlstein says. “Working from the figure had seriously become a lost art.” Deciding to “reinvent it for myself,” he discovered that taking a realist’s view of the nude — though certainly not in an old-fashioned, academic manner — was “more interesting than making squiggles.”

In these works, he drew on everything from Cézanne and the Italian Renaissance to ancient Chinese painting and even what he perceived as perspective in Ab Ex. “I simply used the movements of the figure to make the marks instead of abstract brushstrokes,” he says. “I found it to be so difficult, I haven’t stopped.”

He also found himself increasingly drawn to the work of other artists who were taking a realist approach to the figure, portraiture and landscapes, and he joined a cooperative gallery in Greenwich Village that also included Alex Katz, Lois Dodd and Charles Cajori.

Still, painting the nude was a radical move. Though his compositions today look downright modest, “a number of paintings got into trouble,” he says, recalling incidents at museums in Boston, Philadelphia and the Midwest. “They’d be removed, put into separate rooms. You’d have to show [an ID].” At one museum, where he was scheduled to give a talk, he received a call telling him not to come because of the hubbub.

Pearlstein and his wife, Dorothy, sit in front of Two Models with Kiddie Car Airplane, Chariot, Whirligig and Michelin Man, 2010, which incorporate a variety of odds and ends from his collection.

Pearlstein found recognition in the art world, though there wasn’t much of a market in those days, and it wasn’t unusual to sell only one or two paintings from a show. (Asked if he still owns many of his works, Pearlstein smiles mischievously and nods.) He taught at Yale, where Brice Marden was in his figure drawing class, and then for 25 years at Brooklyn College. “I love the students,” he says. “The smart students were wonderful.”

Back in his studio, within arm’s reach of his first real painting, is his latest work, begun just this morning: a drawn outline of a female torso. Pearlstein encourages his models, who could be termed ordinary-attractive, to position themselves however they like, though he might make adjustments here or there. “Move one of the model’s feet over and you have a totally different composition,” he says, noting that he’s learned a thing or two from a couple of particularly inventive subjects. He then chooses a vantage point. “I start somewhere where a couple of forms overlap and go on from there,” he says. “In the drawing I started this morning, it’s where the woman’s hand and knee meet the base of the demon” — “the demon” being one of his newest props, of course.

He hasn’t finished his salad, but a glance at his watch stops him. “I have to get back to work,” he says with a polite shrug. The model is waiting in the next room, after all, and time is getting away from him.