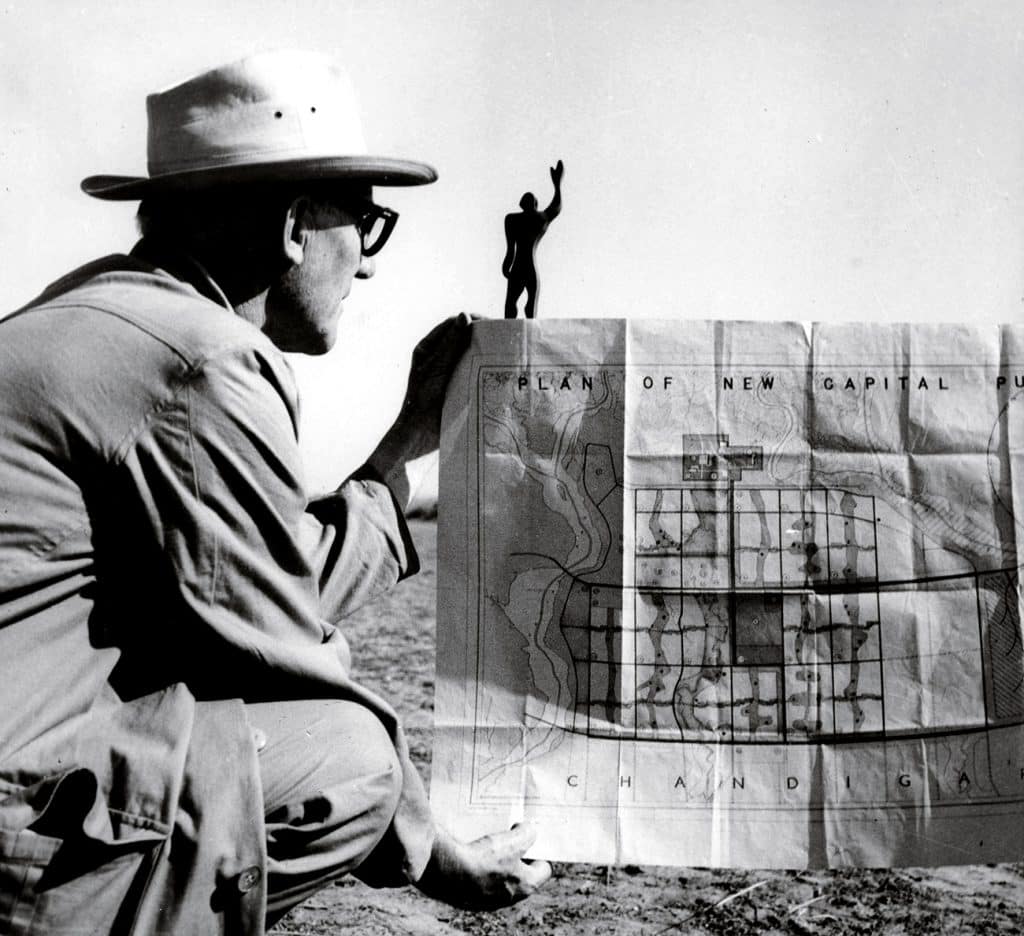

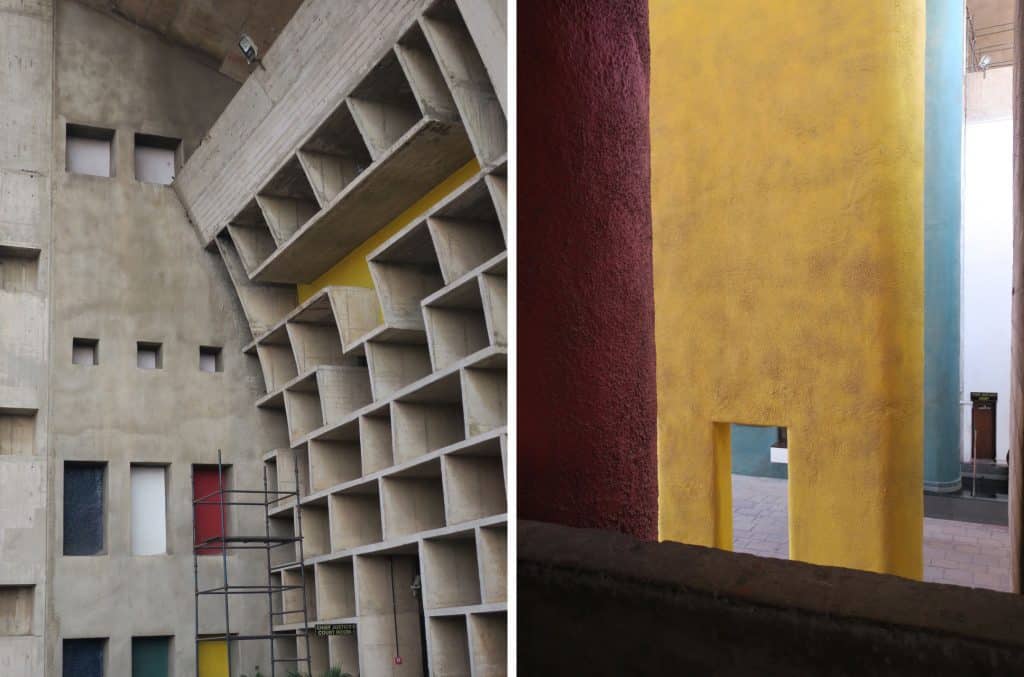

September 1, 2019Pierre Jeanneret at Chandigarh in 1965. His cousin Le Corbusier sought his help in overseeing the construction of government buildings and furnishings for the project ( photo by Denis BRIHAT/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images). Top: Le Corbusier designed the Palace of Assembly in Chandigarh (photo by Artur Debat/Getty Images).

The government buildings in Chandigarh, the capital of India’s Punjab province, are among the reasons Charles-Édouard Jeanneret — better known as Le Corbusier — is considered the most influential architect of the 20th century. The complex, completed between 1951 and 1965, brought modernism to a region seeking a fresh start, placing heroic forms in poured concrete against the flat landscape.

To furnish these structures, including the 750-foot-long Secretariat, the High Court of Justice and the Palace of Assembly, Le Corbusier turned to his cousin, the architect and designer Pierre Jeanneret. Jeanneret, who spent more than a decade in Chandigarh supervising construction of the project, came up with hundreds of designs for chairs, tables, cabinets and lamps suitable for everyone from judges to janitors. Thousands, probably tens of thousands, of pieces were made to his specifications in factories throughout the region. (In addition to the furnishings for the government complex, Jeanneret, who was constructing an entire new city from scratch, outfitted for a number of residential and commercial buildings.)

Pair of Easy armchairs, 1955–56, offered by Galerie Patrick Seguin

Although Jeanneret had designed furniture before, Chandigarh was his greatest challenge — and success. At a time when his contemporaries in Europe and the U.S. were exploring the possibilities presented by aluminum and plywood, he was limited to local materials and traditional construction methods. But those constraints emerged as powerful determinants of form. Soon after arriving in Chandigarh, Jeanneret began making one-of-a-kind pieces for his own house and other small buildings out of found materials like rope and chain. To furnish the government buildings, he turned to solid teak and rosewood. In many cases, the only flourishes on the solidly geometric pieces are his signature “drafting compass” legs.

Library/dining chairs, 1959–60, offered by Patrick Parrish

But within two decades of the buildings’ completion, Chandigaris, seemingly oblivious to the charms of Jeanneret’s wooden furniture, were replacing it with more “modern” — that is, mass-produced — tables and chairs. In 1999, Eric Touchaleaume, owner of the Paris showroom Galerie 54, made a trip to Chandigarh and began purchasing the designer’s pieces, which were piling up in warehouses and junkyards and even being sold for firewood. Back then, Touchaleaume tells Introspective, “I was able to buy very large quantities at auctions organized by the administration.”

Soon he was joined in Chandigarh by other dealers, notably Patrick Seguin, of Paris’s Galerie Patrick Seguin. As the passion for mid-century modernism grew in the U.S. and Europe, so did the market for Chandigarh furniture, which was snapped up by collectors like the gallerist Larry Gagosian, the Belgian interior designer Axel Vervoordt and the architect John Pawson, who calls the pieces “elegant, simple, comfortable, essential.” Kourtney Kardashian uses Jeanneret office chairs around her dining table in Calabasas, California.

It’s a long way from Chandigarh to Calabasas, however, and controversy brewed over whether the furniture — part of India’s cultural patrimony — should remain in that country. Jeffrey Graetsch, a Brooklyn-based dealer who has purchased many pieces in Chandigarh, claims that if dealers hadn’t saved the Jeanneret works, they would have ended up as scrap. Indeed, Jacques Dworczak, the author of a new book about the furniture, says the attention it received in the U.S. and Europe helped “the Indians become aware of their heritage.” Eventually, the export of furniture made for Chandigarh was banned. Although enforcement isn’t perfect, “nothing can legally come out of the city,” Dworczak says.

But a lot already had.

Daybed, 1950s, offered by JF Chen

On 1stdibs, Chandigarh offerings include a set of six library chairs from Galerie Patrick Seguin, priced at over $100,000. The same sum will buy a pair of teak easy chairs from Luxembourg’s Galerie Denoyelle Europe (they have been reupholstered, a fact made clear by the gallery’s photo of them in their previous state of disrepair). For those without $100,000 to spend, Zurich’s P! Galerie is offering a simple wooden library chair (listed as restored in 2016 but with original woodwork and screws) for $4,075. Graetsch currently has 19 Chandigarh items on display at MDFG, his street-level gallery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn (and on 1stdibs), ranging from an iconic ca. 1955 V-leg office armchair ($8,000) to a 1955–56 sofa set designed for the High Court and Assembly ($150,000).

As prices for Jeanneret furniture rose, a new controversy emerged. Were some of the pieces said to come from Chandigarh actually fake? “Sadly, there are many counterfeits,” Seguin tells Introspective.

It’s pretty clear what dealers mean by real: a piece designed by Jeanneret for Chandigarh and made under his supervision. Fake, on the other hand, has a wide range of meanings, not all involving attempts to deceive. For example, if a Chandigarh piece was replaced with one made in the same workshop by the same artisans, following Jeanneret’s design but years after his death in 1967, is it a fake? What about a chair made under Jeanneret but later re-caned and restained? Or a piece that was more extensively restored, to the point where it’s not clear how much of the woodwork is original. (Reportedly, some craftsmen will use pieces of one old Jeanneret chair to make several new ones, each of which can then be said to have authentic components.)

Upholstered easy chairs, 1958, offered by Galerie Denoyelle Europe

Into this heated and confusing market comes Dworczak’s new book, Catalogue Raisonné du Mobilier Jeanneret Chandigarh (Assouline). The lavishly illustrated volume, Dworczak states, “is intended as an educational tool providing as comprehensive an inventory as possible of all the furniture made for the Chandigarh project.”

It certainly seems exhaustive. The listing section includes 34 types of armchairs, 37 varieties of tables and 35 kinds of desks. For each, Dworczak provides historical information and — a service to collectors — prices realized at auction. He says he spent 15 years researching and included only pieces he was sure were by Jeanneret. Those “that could not be formally attributed do not appear in this book,” he told Introspective.

Desk, 1960, offered by Galerie Denoyelle Europe

But is it, as the term catalogue raisonné implies, a complete accounting of Jeanneret furniture for Chandigarh? That would be too much to ask, according to Brigitte Bouvier, the director of the Fondation Le Corbusier, in Paris, who wrote in an email: “There is no scientific and 100 percent reliable catalogue raisonné because most of the original drawings are missing.”

Whether it serves as the last word or not, the book is a welcome addition to the literature on Chandigarh furniture. Another notable book on the subject, Touchaleaume’s 2011 Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret: The Indian Story, is out of print, with copies priced at more than $1,000 on Amazon. (Luckily, Touchaleaume’s website is extremely informative. And he is working on a second edition of the book.) And then there is Seguin’s 450-page book, Le Corbusier & Pierre Jeanneret: Chandigarh, India, which dates from 2014.

But even with reference books at hand, how can buyers of Chandigarh furniture be certain that what they’re getting is real? “I think it’s prudent to know who you’re talking to,” says Seguin, who, not surprisingly, believes it’s worth paying a premium to get the peace of mind that comes from dealing with an expert. Adds Toucheleaume, “Be careful with the too-good deal. It’s too late to play the discoverer. Buy in an established gallery that gives a guarantee of authenticity and agrees to take back the piece in case of problems.”

“It’s like anything else — you’ve got to do your homework,” says Graetsch, who adds that he almost never buys Chandigarh furniture he hasn’t personally inspected first. Among other things, he examines the spots where a piece would normally incur the most damage, such as the bottoms of the legs, which get scuffed when a chair is dragged around, and he looks for other marks, like those left by hits from mops and brooms. “You’d expect to see chips and abrasion and even repairs. When it’s really, really clean, you start to question it,” Graetsch says.

If a piece was used at Chandigarh, you should be able to find photographic evidence of that. Graetsch recently bought from a French auction house a floor lamp said to be by Le Corbusier himself. (Although most of the Chandigarh pieces are attributed to Jeanneret, some are by Jeanneret and Le Corbusier and a few by Le Corbusier alone.) It was supposed to have come from the Yacht Club, which Le Corbusier designed. When the lamp arrived, however, it seemed to have different proportions from one shown in early photographs of that building’s interiors. That made him doubt its authenticity, and he returned it to the auction house.

Still, the fact that a piece hasn’t been documented doesn’t mean that it isn’t authentic. Jeanneret’s output “is so much bigger than people realize,” Graetsch says. “We’re still finding pieces that we’ve never seen before. What I always say to people is, ‘Look at the soul of the piece. If you don’t trust something, don’t buy it.’ ”

Set of six V-leg armchairs, ca. 1955, offered by MDFG

And if an expert you’re working with sees a piece and says, “I don’t like it,” take heed. “That’s a kind of code,” Graetsch says, explaining that in the collegial world of dealers and advisors, “no one ever says, ‘This is fake.’ ”

One thing is very, very real: The pieces created by Jeanneret have become part of the modernist canon. “This work is known and respected worldwide, as it deserves to be,” says Dworczak. Toucheleaume agrees. “When you buy furniture by Jeanneret and/or Le Corbusier from Chandigarh, you are buying a piece of history,” he says, adding that although there are a lot of pieces on the market now, the absolute numbers are small “considering the global infatuation with collectible furniture.” And, he continues, “some models have already become unavailable on the market. I am convinced that in a decade or so, it will be very difficult to put six matching chairs around a table.”