November 9, 2025The fame came through a deletion. In 1953, Robert Rauschenberg obtained a drawing from Willem de Kooning. And he erased it. At first glance, this seemed like an art-world stunt, a bratty thumbing of the nose at the reigning Abstract Expressionists.

But de Kooning was a willing participant, deliberately choosing a drawing he would actually miss, and Rauschenberg spent weeks painstakingly rubbing away each mark until only the faintest ghost of gesture remained. The act wasn’t rebellion or vandalism so much as a cleaning of the slate for a new form to emerge: contemporary art.

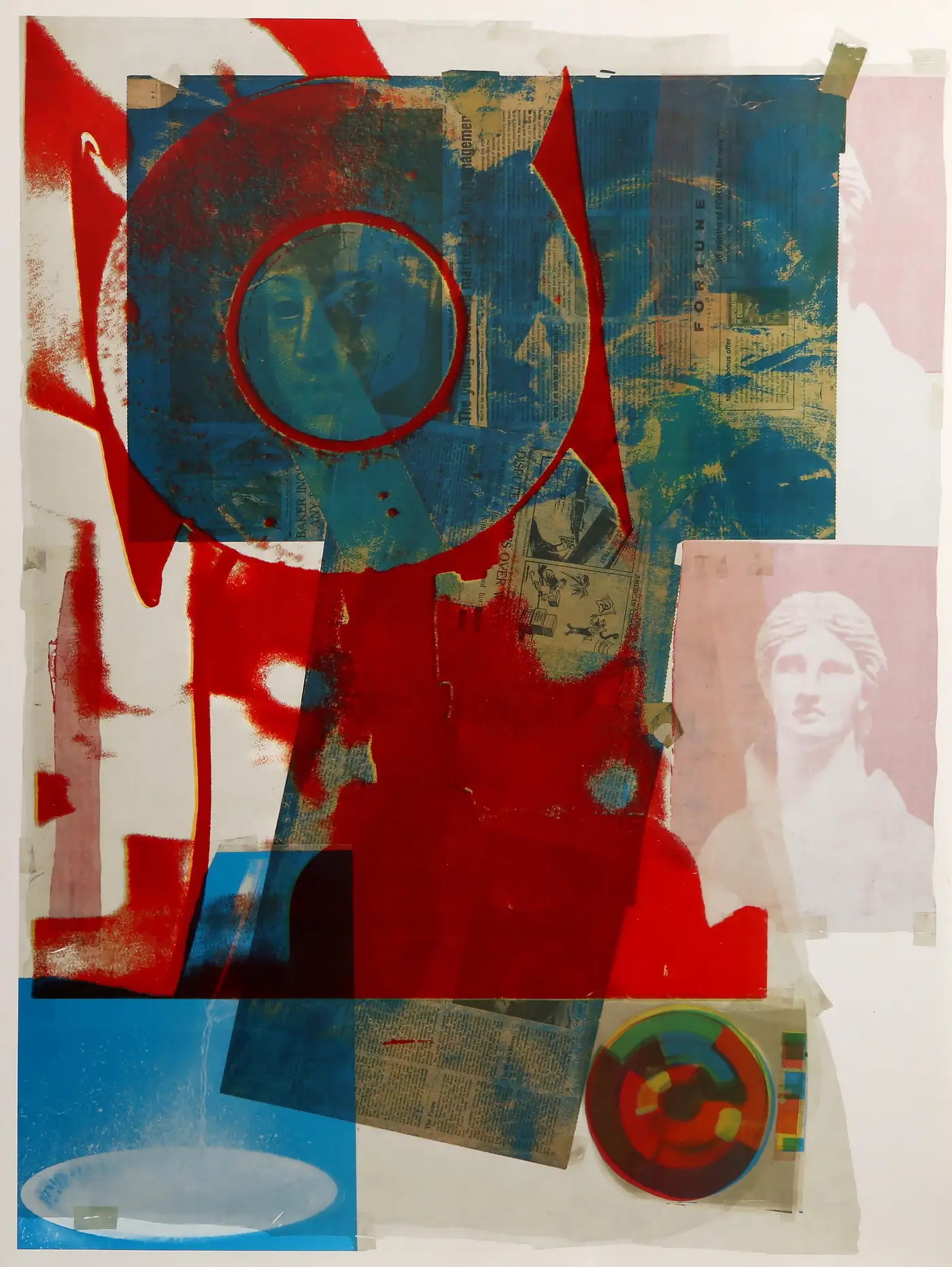

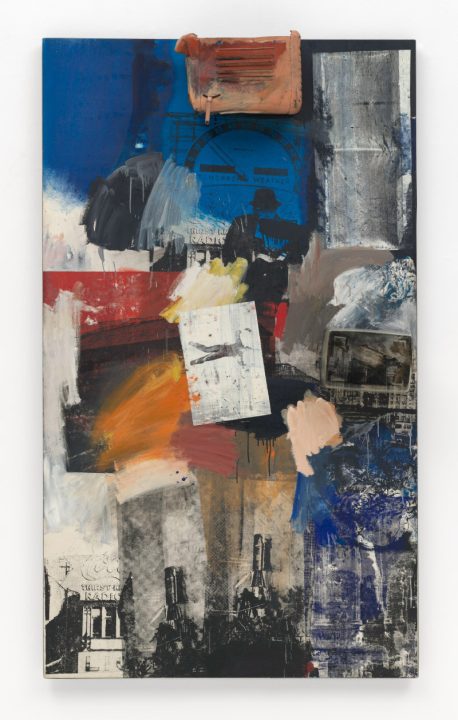

Soon after, Rauschenberg began to accumulate — images, ideas, mediums, discarded objects, artist friends, disparate collaborators, new technologies. From that blank page came a lifelong appetite for combination: his popular “Combines,” which merged painting and assemblage; the silkscreen paintings that layered news photographs, television stills and sociopolitical fragments; the performances and stage sets created with Merce Cunningham and Trisha Brown; the experiments with master printmakers, craftspeople and engineers. A gathering of the world into art.

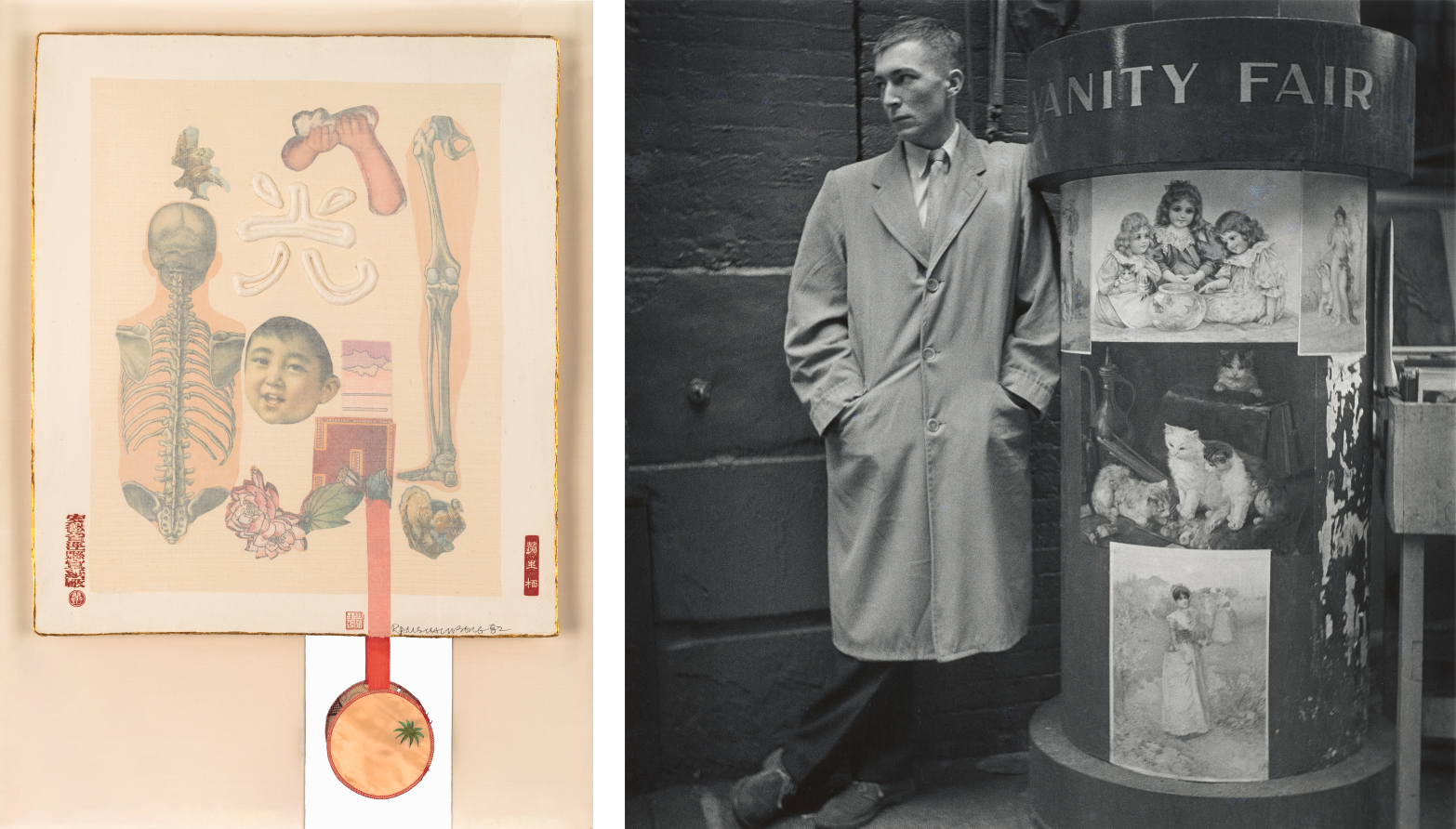

Rauschenberg’s genius for collecting and rearranging is very apparent this year. What would have been the artist’s 100th birthday is being celebrated with tribute shows everywhere from Hong Kong’s M+ museum to Houston’s Menil Collection, Michigan’s Grand Rapids Art Museum to Milan’s Museo del Novecento, and more than a dozen places in between — proof of how deeply his restless vision reverberates across cultures and continents.

Many of the shows return to an aspect of Rauschenberg’s practice that feels apropos to our age of endless scrolling and AI Frankensteining: photographic imagery and collage. Long before digital layering or Photoshop, he understood that pictures could be lifted, multiplied and recombined to form a new visual language. He clipped from magazines and newspapers, shot his own 35mm photos of street corners and dance studios and layered them onto metal, canvas and plexiglass in ways that look surprisingly 3D in person. Each surface became a living archive.

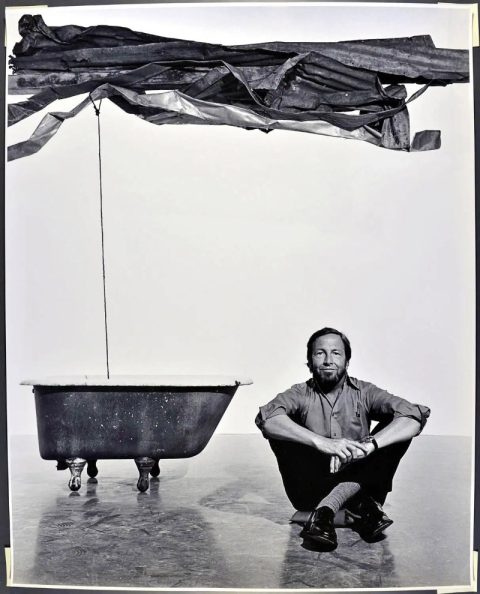

Born in the Gulf Coast oil town of Port Arthur, Texas, Rauschenberg returned to the gulf in 1970, settling on Florida’s Captiva Island, where he lived and created until his death, in 2008. But it was New York City (his off-and-on home base from 1949 through the ’60s) that shaped his exuberant, crowded, cacophonous sensibility.

That’s why Rauschenberg’s centennial feels most resonant in Manhattan, where three concurrent exhibitions trace different facets of his kaleidoscopic career. At the Guggenheim Museum, “Life Can’t Be Stopped” places his largest silkscreen painting, the panoramic Barge (1962–63), at its center, exploring how the artist integrated mass-media imagery into paintings, prints and kinetic sculpture.

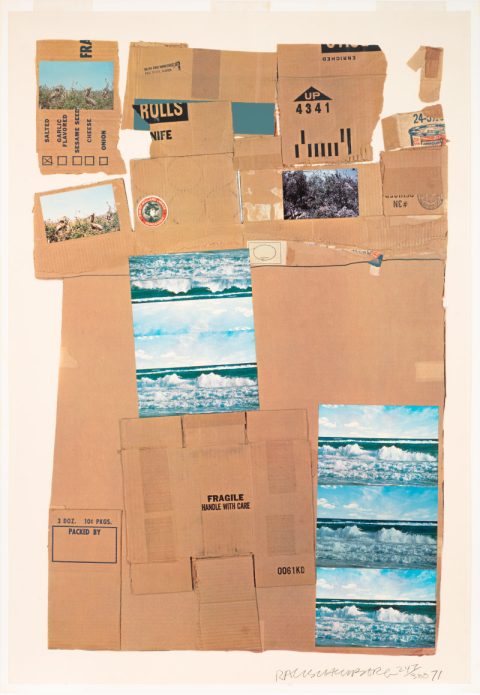

And at New York University’s Grey Art Museum, “Handle with Care” draws on NYU’s collection of Rauschenbergs to explore his environmentalist side. Meanwhile, the Museum of the City of New York’s “Pictures from the Real World” focuses on Rauschenberg’s 1950s–80s photographs of the city where his fascination with collage, media and daily life took root.

Introspective spoke with the curators of the three New York exhibitions about Rauschenberg’s boundless curiosity, his enduring influence and the meaning of his work today.

What aspects of Rauschenberg’s work did you want to highlight through your exhibition?

Sean Corcoran, Curator of Prints and Photographs, Museum of the City of New York: Rauschenberg’s photographs are rarely exhibited, yet his interest in photography is central to his art-making practice. We wanted to forefront this aspect of his work while highlighting the impact of his longstanding relationship to New York City.

The photographs provide an insightful window into how he perceived the city through the ready-made scenes of daily life.

Joan Young, Director of Curatorial Affairs, Guggenheim Museum: Given the Guggenheim’s history with the artist — the museum organized an extensive retrospective of his work, curated by Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson, in 1997 — we felt it would be a wonderful opportunity to present a selection of works from the collection, notably the incomparable Barge (1962–63), which has not been exhibited in New York since 2001.

Using Barge as the focal point, I developed a checklist that focuses on the artist’s integration of mass media and the photographic image into drawings, paintings, prints and sculpture from the early nineteen fifties through the nineteen nineties.

Phoebe Herland, Rauschenberg Curatorial Intern, Grey Art Museum: There really isn’t a lot out there related to the ecological aspect of his work. The climate is such a source of anxiety for young people, and I thought it would be great to see how an artist working half a century ago acted upon environmental issues just as they were beginning to arise: oil spills, endangered species, et cetera.

Maybe works produced for humanitarian or environmental reasons were dismissed in the past, as if because they had social aims they could not be artistically interesting. That has not at all been the case. He’s really experimenting in these prints and taking them seriously. We should, too.

Rauschenberg famously blurred boundaries between art and life. How do you see that playing out in your exhibition?

Young: The selection of works illustrates the interest that Rauschenberg had in media imagery, from his use of images from such popular magazines as Life, Esquire, National Geographic and other sources in his transfer drawings — with examples from 1952 to 1980 on view — and for his “Silkscreen Paintings” (1962–64), to the incorporation of his own photographs of his travels and surroundings in later works.

For me, his practice is a reminder of the important role of an artist as a chronicler of their time, one who might enable viewers to see the world around them through a new lens.

Corcoran: In the nineteen fifties, when Rauschenberg was a struggling artist, he walked the city streets gathering interesting discarded materials that he might later include in his “Combines.” Many years later, when he walked those same streets with his camera, he continued to look at the world around him to gather up images of overlooked remnants of American culture.

Herland: Rauschenberg often worked with the news playing on TV, often muted, while the radio played simultaneously, so these works were purposefully cultivated in an environment of information overload that anticipates what’s happening today with TikTok and Instagram and push-notification headlines.

It’s important to note that Rauschenberg was originally from an oil town in Texas, with many formative memories made in the bayou. He also lived and worked in Captiva starting in 1970. So, his imagery about oil spills and brown pelicans, which were then on the verge of extinction, reflects his genuine, homegrown and firsthand concerns.

Collaboration was central to Rauschenberg’s practice. How does that spirit come through in your exhibition?

Corcoran: Rauschenberg’s relationship to the rich artistic community of New York City is best exemplified in his early photographs taken throughout the nineteen fifties and into the nineteen sixties. Here, we see photographs of his wife, Susan Weil; artistic collaborators, including Merce Cunningham and David Tudor; and fellow artists and lovers Jasper Johns and Cy Twombly.

Young: Revolver II, from 1967, is evidence of his keen interest in working with engineers to expand the notion of painting by integrating light, sound and, in this case, motion.

Did anything surprise you while researching or assembling the exhibition?

Corcoran: I was most surprised by looking at Rauschenberg’s contact sheets. They reveal how efficient he was as a photographer. He found a subject of interest and would make two or three frames. He worked quickly. He did not linger. He was decisive and would then move on to new subjects. Rarely have I seen other contact sheets where the photographer had such a high success rate when making his photographs.

Herland: While several of the works on view were produced for a specific humanitarian purpose, in collaboration with various organizations such as the Academic and Professional Action Committee for a Responsible Congress, the Pan American Development Foundation or his own Change, Inc., the environmental and social aspect of a work like General Delivery, 1971, wasn’t immediately obvious to me.

Given all this, it was also surprising when I saw a print in the collection that was produced for Mobil Oil, a work he perhaps cheekily called Deposit. He did it knowing that proceeds would go to Change, Inc, but it’s a morally gray area.

If you could display or take home one Rauschenberg piece, what would it be?

Herland: Some of the most overt environmental prints in Rauschenberg’s oeuvre are not in NYU’s art collection and so not on display in our show, but I would have loved to have had them. These include his Earth Day poster from 1970, his print Burrough’s Dream from 1972 and the one he made for the UN’s Earth Summit in 1992. I see all three are available on 1stDibs!

If I could take one from the show home it would be General Delivery. I just love the colors, and it’s so pivotal.

Corcoran: If I had the space in my home, I could happily live with Rauschenberg’s Wet Flirt (Urban Bourbon), 1994, for the rest of my life. This painting contains several silkscreens of his New York photographs and is an excellent example of how he could masterfully bring together a combination of disparate images to create something altogether new.

Did you ever meet Rauschenberg?

Herland: Alas, I’m too young! But Bob used to come to the Grey a lot — his studio on Lafayette is right around the corner from our current location — and there are people on staff here who knew him. I love hearing their stories.

Young: The 1997 retrospective was the first exhibition for which I was part of the curatorial team at the Guggenheim. My primary memory of Bob from that time is of his radiant smile and laugh.[END]