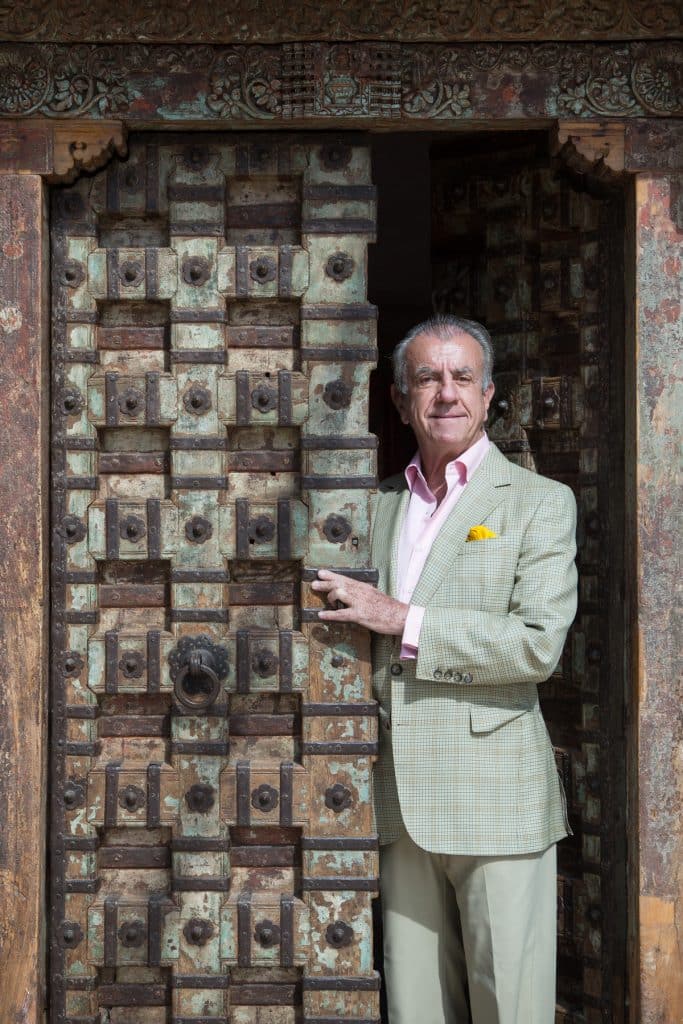

March 24, 2019Mexico City antiquaire Rodrigo Rivero Lake poses in his apartment-cum-showroom with one of his most impressive finds — a Japanese-influenced Viceregal Mexican screen, ca. 1690. Top: In the RRL gallery, a 17th-century Gobelins tapestry provides the backdrop for a Guatemalan gilt and polychrome nativity scene from the same period.

Rodrigo Rivero Lake’s showroom and sumptuous residence sprawl lavishly across the 10th floor of a handsome modernist building in Polanco, one of Mexico City’s most desirable neighborhoods. The area, bordering the northern edge of Chapultapec Park, is dotted with chic cafés, swank boutiques and green spaces ornamented with fountains and formal gardens.

But nothing in the building’s marble-clad foyer, tastefully appointed with a Noguchi coffee table and Le Corbusier sofa, prepares a visitor for what awaits above — except perhaps for a very good, old, carved-gilt-wood Buddha.

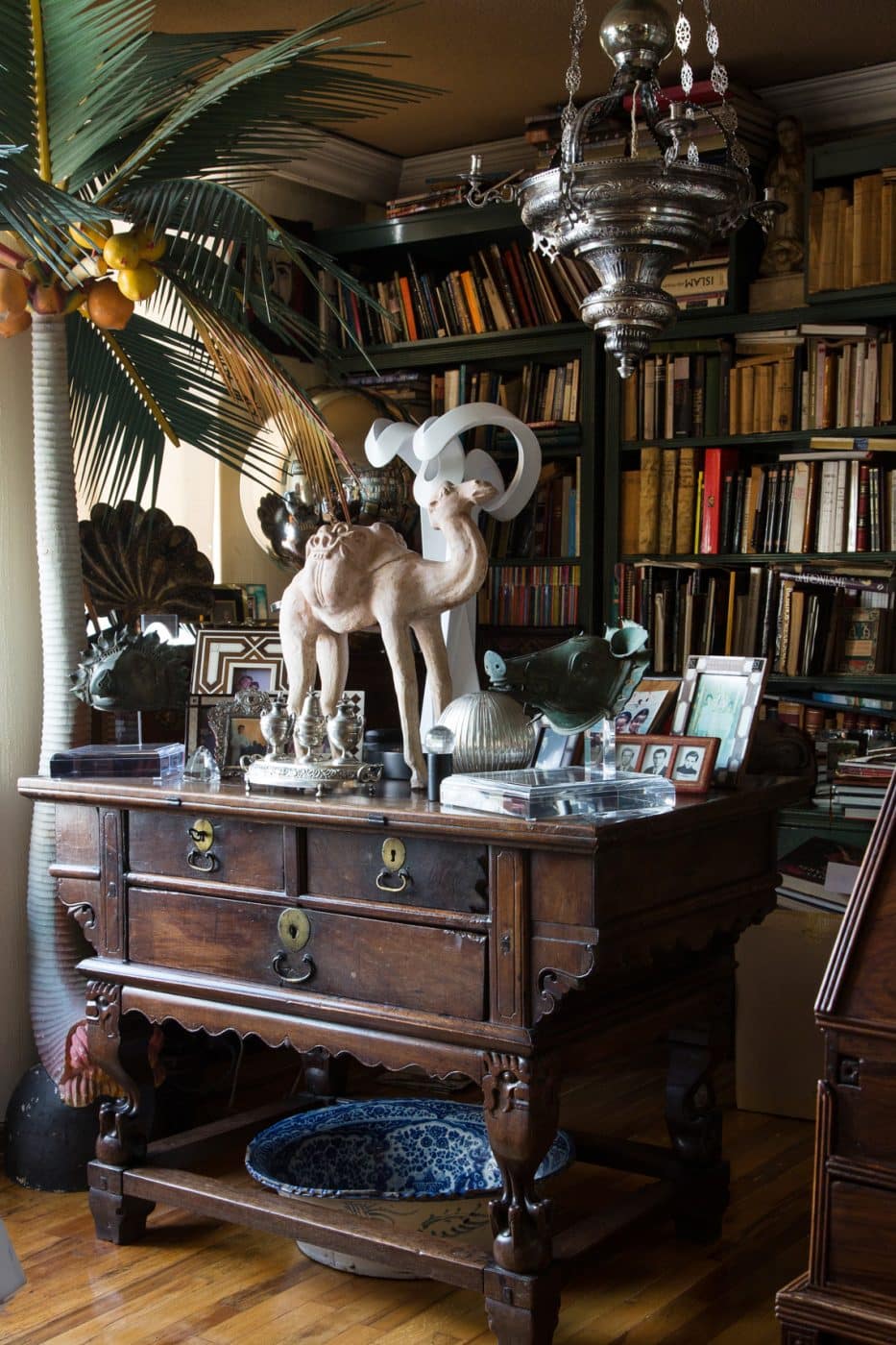

When the elevator doors open on the penthouse suite, phones ring, a staff of six bustles about, and your eyes dart among so many treasures it’s dizzying. Room after room features outstanding examples of 17th- and 18th-century carved and polychrome Spanish Colonial settees. An exquisite 17th-century oil on canvas of the Virgin Mary surrounded by angels glows against a tapestry-covered wall. More of the same is found at the elegant RRL gallery nearby, as well as in a warehouse filled with a staggering inventory of art, furniture and architectural elements, most notably from India and Southeast Asia.

The name Rodrigo Rivero Lake is synonymous with the highest-quality Spanish Colonial furniture and fine and decorative arts. The dealer is also a pioneer in the preservation of architectural elements, especially ones from Asia, and the only Mexican member of the renowned Oriental Ceramic Society, in London. A curator of museum exhibitions worldwide, Rivero Lake is esteemed by his peers — including those at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum and the San Antonio Museum of Art, to name a few — as well as by collectors of the most discriminating taste. An RRL imprimatur insures that a piece is not only authentic but the finest example of its kind.

In the showroom, ornate objects crowd every surface. The piece in the center is a Viceregal inlaid and engraved marquetry coffer from Oaxaca.

Rivero Lake has a gracious, even dashing, old-world bearing. He’s the scion of a grand old Spanish family, with forebears on both sides of the Mexico–U.S. border. For years, he worked with notable clients privately, but RRL is now open to the public. “I don’t usually follow the buyers,” he says crisply. “People contact us. They call me if someone needs something.” A polymath with a law degree, Rivero Lake chose to forgo a legal career in favor of the world of antiques, which had intrigued him since he was a child. He’s the author of countless scholarly articles and books, such as Namban: Art in Viceregal Mexico, about the confluence of Japanese and Spanish cultures. His work, which has been his passion — no, “obsession,” he corrects — for the past 50 years, has yielded a collection and a curatorial record mapping New Spain (as Mexico was known during the Viceregal era) and lands far beyond.

Carved wooden arches from India decorate the mirrored walls of Rivero Lake’s dining room. With no electric lighting in the space, Rivero Lake is known for hosting dinner parties by candlelight.

The narrative thread of Rivero Lake’s work weaves together Spanish descendants and indigenous people in the Americas and unspools along the galleon trade routes that extended throughout Asia, Europe and North Africa when Spain was the global power. How else might you explain a 17th-century Chinese-export porcelain soup tureen decorated with the arms of a Spanish count? Or an exquisitely painted, mother-of-pearl-encrusted, multipanel screen, circa 1690, that might have graced a shogun’s palace save for the depiction of Spanish barks engaged in battle? The panels had been broken up and scattered to the four corners of the earth; it took Rivero Lake years of keen sleuthing and serendipitous encounters across several continents to reunite them.

Covetable lacquer boxes scattered on a table reflect the exchange of Spanish and Asian artisanal techniques and decoration. One has a heraldic lion; another, a flower resembling a Japanese fan. “My preoccupation has been searching for pieces that have a life of their own,” Rivero Lake explains. “I’m curious about the magic that causes one piece to be preserved and about the spirit between us and the object. It has its own vibration and life. Once you start talking to these pieces, they start talking back.”

A 16th-century Spanish-school carving of Saint John the Baptist is among the many works in the dealer’s warehouse.

And so they do as you wander through the collection. An array of exquisitely carved ivory saints and delicate figures of Buddha — an entire celestial court — perches atop a marquetry vargueno inlaid with ebony and mother-of-pearl that was made for Portuguese colonials in Goa. An exuberant, expressionistic rooster painted in vibrant aniline colors on tissue paper punctuates a far wall. It’s the work of mid-century artist Jesús Reyes Ferreira, known as Chucho Reyes. A Mexican icon, he was a dear friend of Luis Barragán and Mathias Goeritz and was admired by Chagall and Picasso.

“I have four hundred Chuchos,” remarks Rivero Lake, forging ahead to the airy dining room, where a massive, elaborately carved late 17th-century Indian architrave from Gujarat lines the mirrored walls. Apparently, entire facades in the region — whole towns — were abandoned. The extraordinary entablature is the tip of the iceberg. RRL’s inventory of furniture and architectural elements comprises in the vicinity of 13,000 pieces, with 66 pairs of doors alone.

A heroically scaled, totemic carved-wood sculpture stands sentinel in a top-floor atrium leading to a terrace with commanding views. A modernist masterpiece? Brancusi? No, this impressive monolith with its timeless presence is a 19th-century relic of the Naga people, one of 70 pieces sourced from the region where India borders Tibet and Myanmar. Nearby, a sensuously weathered granary door from the same ancient tribal group looks like a portal for time travel.

An untitled 1984 work by Mexican painter and sculptor Pedro Coronel hangs in Rivero Lake’s living room.

This piece, like so many on display, suggests that Rivero Lake is possessed of a sixth sense for treasure. The range and quality of his holdings are a testament to his uncanny knack for pursuing art and antiques around the globe. But those interested in acquiring his finds should bear in mind that his supply, though vast, is not inexhaustible. “The Spanish Colonial pieces are increasingly difficult to source,” he says. “There have been a lot of revolutions. There’s not much left.”

Talking Points

Rodrigo Rivero Lake describes a few outstanding pieces from his collection.