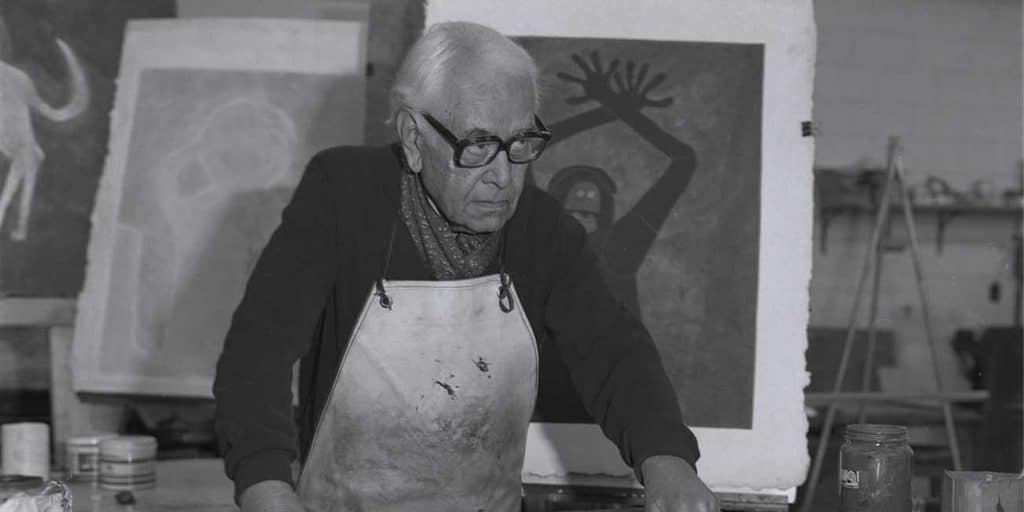

February 9, 2020The celebrated Mexican-born artist Rufino Tamayo helped develop printmaking techniques that, 30 years after his death, continue to evolve. Above: Hombre con sombrero alto (Man with Tall Hat), ca. 1930, by Rufino Tamayo. Image courtesy of LACMA. Top: Tamayo at the Mixografia Workshop in Mexico City, 1980–85. Photo courtesy of Mixografia, ©Shaye Remba

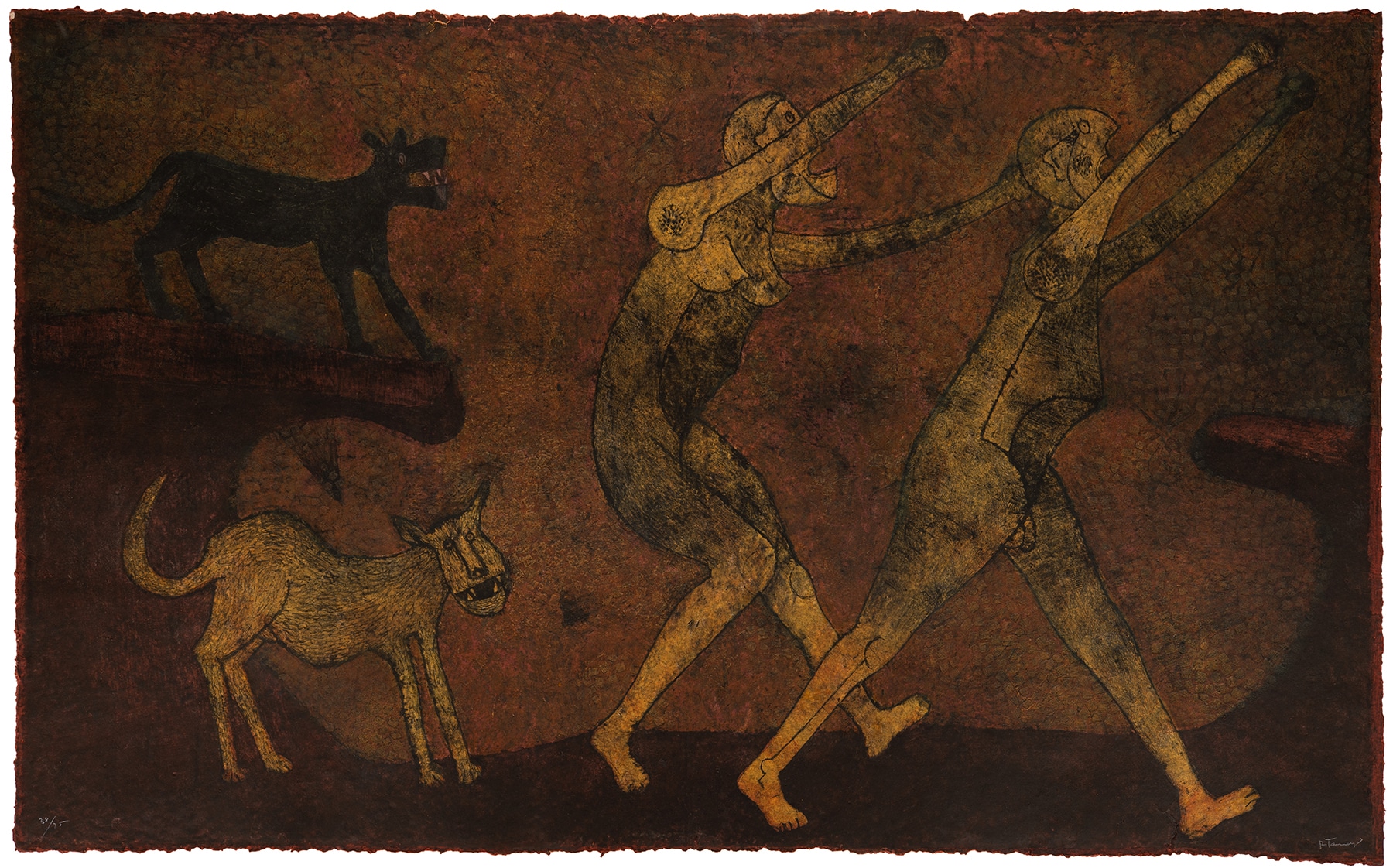

Rufino Tamayo’s unsettling print Dos personajes atacados por perros (Two People Chased by Dogs), 1983, is far from your typical lithograph. At about 100 inches long and 60 inches wide, it’s the size of a wall mural and the largest lithograph ever made. Also, parts of it are in relief, with rich texture throughout. The work combines traditional lithography (printing from a flat surface that’s treated to repel ink everywhere except where the image appears) with Mixografia, a unique process, involving a three-dimensional plate, that Tamayo developed with the help of a master printmaker.

Tamayo, a giant of Mexican modern art who lived from 1899 to 1991, is largely known as a painter and muralist. Less familiar are his many print works and printmaking advances. Tamayo’s legacy in that medium is celebrated in the exhibition “Rufino Tamayo: Innovation and Experimentation,” currently on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s gallery at Charles White Elementary School.

Tamayo and Luis Remba (right) with their wives, Lea Remba (far left) and Olga Tamayo, at Mixografia, 1980–85. Photo courtesy of Mixografia, ©Shaye Remba

“Tamayo’s prints span the seven decades of his career, and from very early on he was combining techniques to push the medium in new directions,” says Rachel Kaplan, assistant curator of Latin American art at LACMA. “Now, almost three decades after his death, the Mixografia technique he envisioned continues to develop and evolve, with contemporary artists adopting the process.”

The exhibition contains 20 of Tamayo’s works on paper, as well as a handful of Mesoamerican sculptures. Tamayo, who was of Zapotec descent, included in his prints and paintings details and figures from Mesoamerican artworks, of which he amassed a significant collection that is now part of the holdings of the Museo Rufino Tamayo, in his native Oaxaca.

A master printer inks the lithographic stone for Dos personajes atacados por perros. Photo courtesy of Mixografia, ©Shaye Remba

Tamayo created Two Personages Attacked by Dogs in an edition of 75 in the 1980s, during the last decade of his career. The scene depicted suggests the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the garden of Eden. Alternatively, Kaplan observes, “it can be read as a response to the state of the world in that period, with pervasive feelings of angst and anxiety.”

Dos personajes atacados por perros (Two Personages Attacked by Dogs), 1983. Image courtesy of LACMA

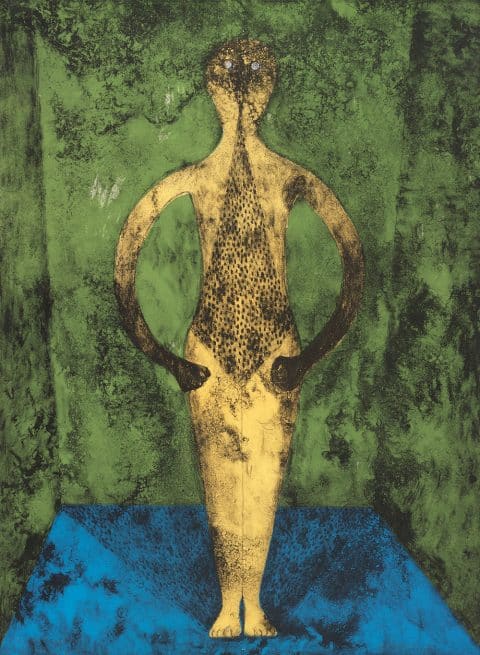

Two Personages exemplifies Tamayo’s ability to tap into universal emotions. All his pieces, with their rich, atmospheric colors and many dark, stylized silhouettes, have a dreamy, folkloric quality. Living in his native Mexico as well as the U.S. and Europe, Tamayo was affected over the course of his career by Surrealism, Cubism and Expressionism. The foreboding creatures that often show up in his work — like the feathered serpent in the 1978 mixograph Quetzalcoatl and the moon dog in the 1973 lithograph Perro de Luna, both available on 1stdibs — reflect his interest in allegory, as well as the influence of Mesoamerican cultures, whose deities often took the form of animals.

Tamayo was orphaned at around age 10 and moved from Oaxaca to Mexico City to live with an aunt. He studied briefly at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts and worked as a draftsman at the National Museum of Archeology. In the 1940s, before his first major retrospective in Mexico City, Tamayo differentiated himself from the Mexican artists who were known as “the great three”: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

From left: Torso blanco (White Torso), 1978; Hombre con brazos abiertos [El predicador] (Man with Open Arms [The Preacher]), 1984; Personaje con red (Personage with Net), 1982. Photo courtesy of LACMA

Unlike them, he was interested in art as a means of poetic and allegorical expression, rather than as a vehicle for politics or descriptive realism. “He was very savvy, and getting himself into the artistic conversation in this way brought a lot of attention to his work,” Kaplan says. As Tamayo’s career progressed, he promoted himself as a painter and received major mural commissions around the world.

All the while, he was making prints, in part as a preliminary way of fleshing out his ideas. He worked with master printmakers and became involved in every step of the process — experimenting, for instance, with combining etching and lithography. In the early 1970s, Luis Remba, of the well-known printmaking studio Taller de Gráfica Mexicana, in Mexico City, invited him to create some lithographs there.

Tamayo sits in front of a version of Dos personajes atacados por perros at Mixografia. Photo courtesy of Mixografia, ©Shaye Remba

At the time, Tamayo was adding dust and powders to his paints to give his paintings texture. He asked Remba to develop a process that would allow him to create three-dimensional prints. Remba enthusiastically took up the challenge and came up with a process he called Mixografia. Tamayo would create a maquette, using a variety of materials, and Remba would use it to make a printing plate with texture and dimensionality. No one had ever done this before.

El personaje (The Personage), 1975. Image courtesy of LACMA

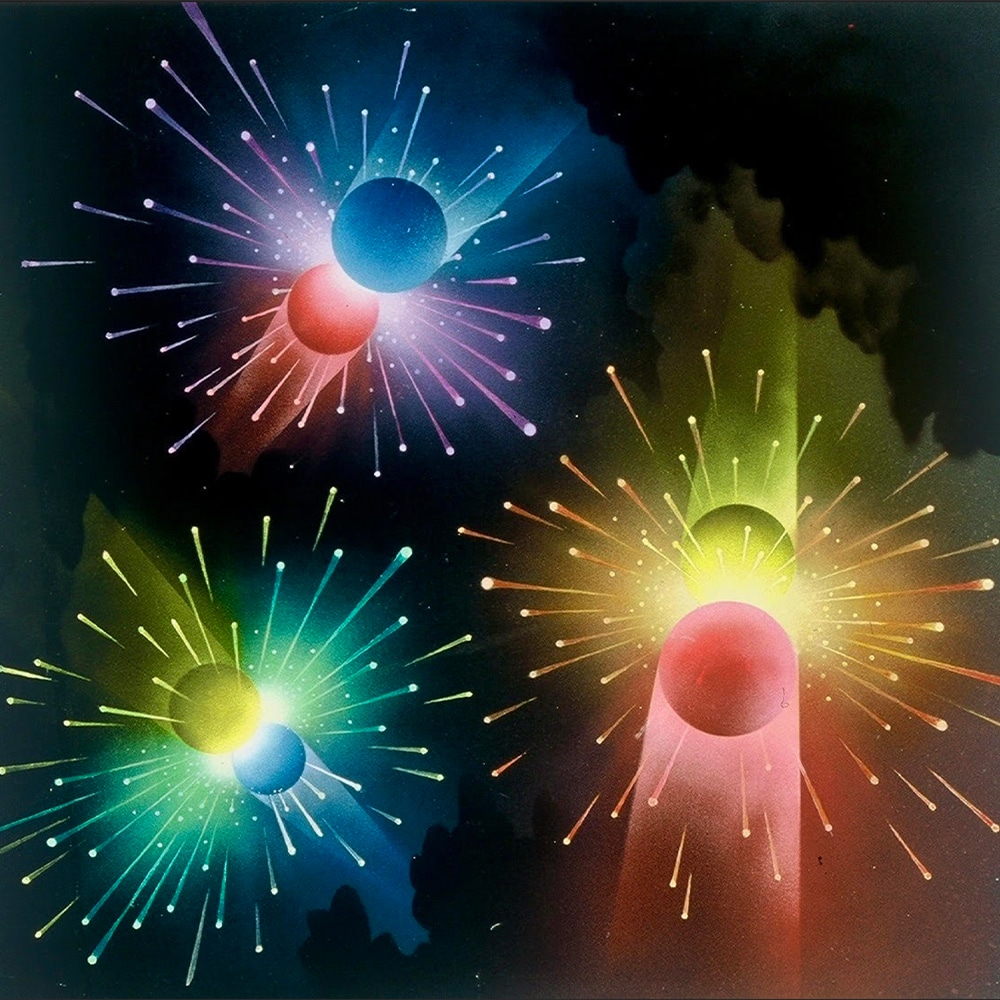

“Tamayo totally embraced” the method, recalls Shaye Remba, Luis’s son, who is now the director of the workshop. Commercial paper often tore under the pressure of the 3-D printing plate, so the studio began producing its own handmade version, pressing the plates into wet pulp, which increased the volume. It also resulted in better absorption of the pigment, which made Tamayo’s signature brilliant colors even more saturated, as evidenced in the blazing reds and pinks in the mixographs Hombre (Man), 1976, and Figura en rojo (Figure in Red), 1989 (both available on 1stdibs). In the exhibition, his vivid colors are on display in numerous works, including the mixograph Hombre con brazos abiertos (Man with Open Arms), 1984, showing a human silhouette reaching toward the sky, and the lithograph Mujer temblorosa (Trembling Woman), 1974, in which the figure is just subtly suggested, with splatters of color.

Ultimately, the studio was renamed Mixografia, and the family relocated it to Los Angeles. Today, it includes a gallery, which houses the lithographic stone for Two Personages — the world’s largest, which is too heavy to be loaned out. Since Tamayo’s death, in 1991, many contemporary artists, including John Baldessari, Kiki Smith and Ed Ruscha, have collaborated with the workshop. Remba works with each, tweaking the technique to suit his or her needs.

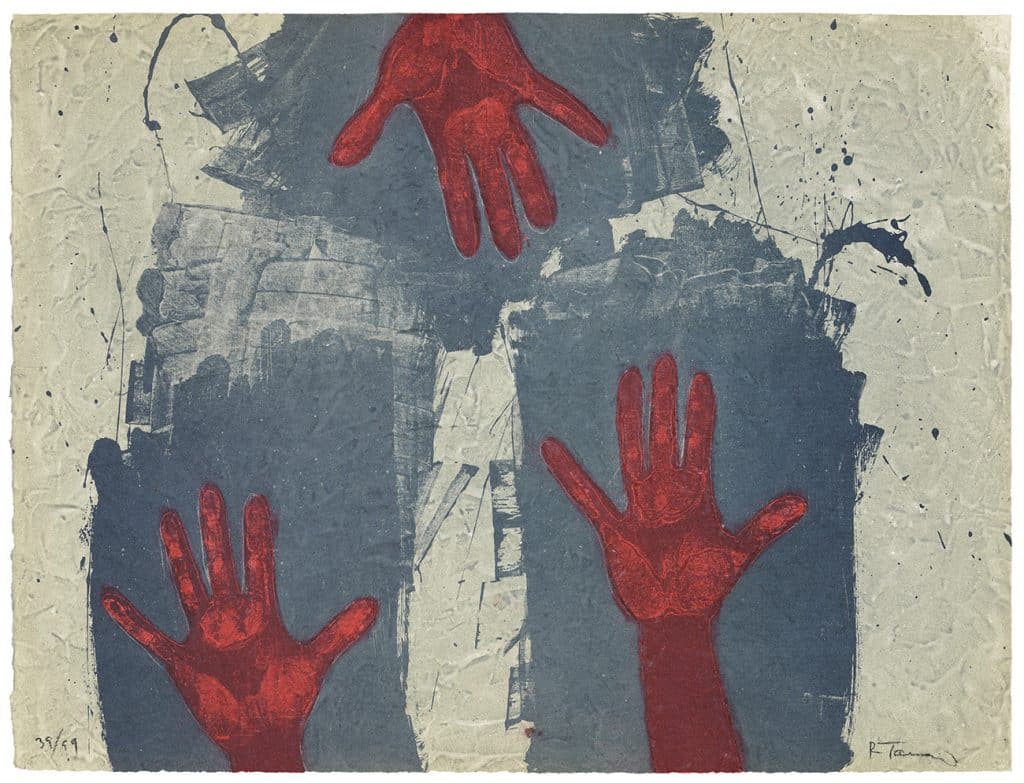

Manos sobre fondo azul (Hands on Blue Background), 1979. Image courtesy of LACMA

Tamayo’s prints are having a particular moment right now, with the LACMA exhibition and a recent exhibition about Mixografia at the Bowers Museum, in nearby Santa Ana.

“These exhibitions are a reminder of all that he accomplished, as one of Mexico’s most beloved artists,” Remba says. “I remember traveling to Oaxaca with him in the eighties, and people would cheer for him in the streets.”