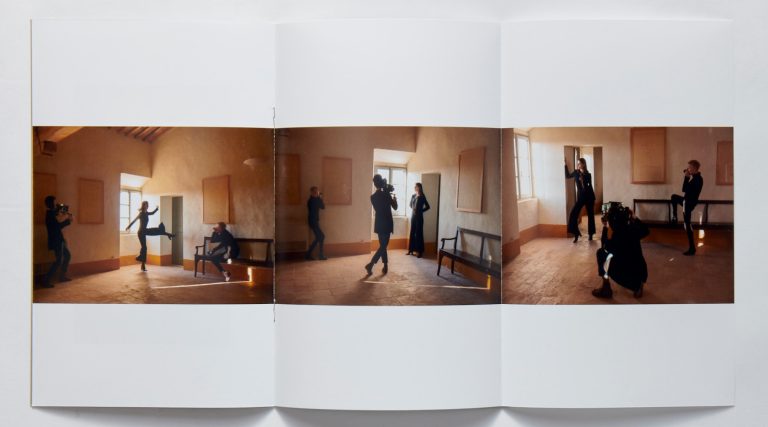

May 31, 2020Supreme, the 25-year-old cult streetwear brand founded by James Jebbia, has achieved status through collaborations with fashion houses like Louis Vuitton and Comme des Garçons. Above: An advertising image from Supreme’s Fall/Winter 2017 collaboration with Louis Vuitton (photo by by Terry Richardson). Top: A spread from the recent Phaidon book Supreme. Aerial video by Ben Solomon

The Christie’s online auction “Handbags X Hype” closed bidding last December. The “handbags” of the title were the usual luxury designs from heritage brand behemoths like Hermès and Chanel. But what was “hype,” and what was it doing in a sale aimed at collectors that are decidedly upscale, if also trying to be clever? It turns out that “hype” referred to designs by Supreme, a 25-year-young cult streetwear brand with a subversive attitude beloved by its fervid followers.

Two lots achieved the auction’s top price of $125,000. One was an Hermès white niloticus crocodile Birkin bag, a category that regularly achieves staggering sums; the other was a first timer on the block, a mouthwatering scarlet 2017 Louis Vuitton x Supreme Malle trunk, one of many now-legendary Supreme limited collaborations. Wait, what? Didn’t Louis Vuitton sue Supreme for brand infringement in 2000? It did indeed. But both companies saw the lucre and became commercial allies.

Phaidon recently published the simply titled Supreme to mark the company’s 25th anniversary. The 350-page book is actually Volume 2, covering the years 2008 through 2017; the first came out in 2008. It is an arresting pictorial biography of people and places and gear, each image presented as cleanly as in a gallery retrospective, on a white background and identified only on a final page of credits. Prose is sparse. There is a brief, heady introduction by culture critic Carlo McCormick that concludes, “But you’re wearing art.” And longtime Supreme acolyte screenwriter Harmony Korine contributes a stark contextual poem: “We got lost in it/got tossed in it/it was beautiful/it was supreme.” It is the visuals — by such provocative photographers as Terry Richardson, Larry Clark, Alasdair McLellan and Yanis Chabane — that eloquently document Supreme’s astonishing growth from street to global cred, much to the incredulity of the mainstream mass market.

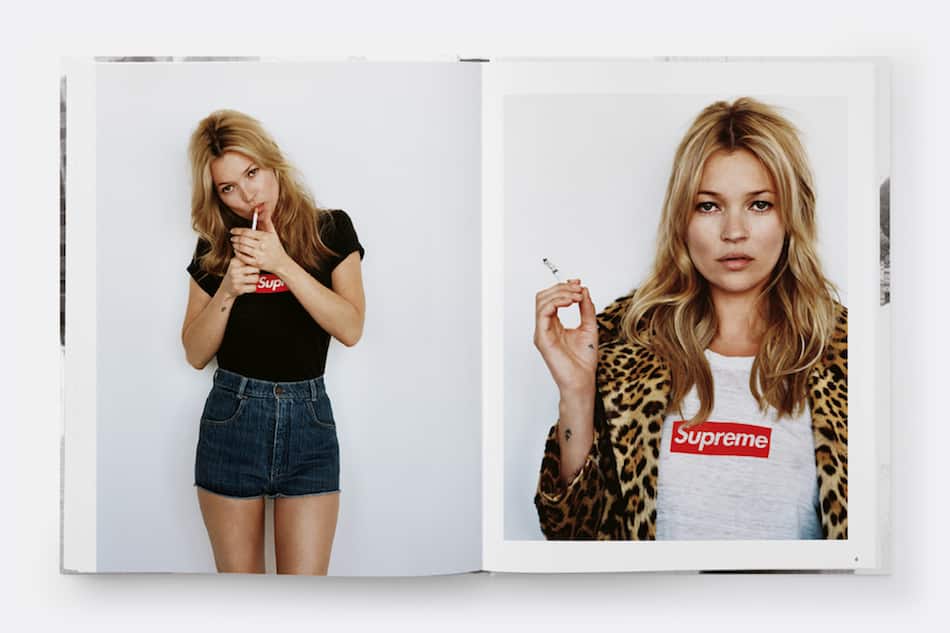

Kate Moss Supreme, 2017, Alasdair McLellan

How did Supreme founder and director James Jebbia do it? Although habitually eschewing interviews as well as prose, the 56-year-old British ex-pat opened up to Vogue in August 2017, just before selling half his company to the Carlyle Group for $500 million, implying a value for the whole of $1 billion, give or take. Dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, he explained that he “always really liked what was coming out of the skate world. . . . It was less commercial — it had more edge and more fuck-you type stuff.”

After a short-lived stint as a salesman for downtown Manhattan store Parachute and running a Stüssy branch as well as his own retail outlet, Union, in 1994 Jebbia opened Supreme, “the cool, cool shop … no big brands or anything.” He sold skateboards and sneakers, tees and hoodies while movies like Mean Streets and loud hip-hop played in the background, attracting a young downtown crowd of skateboarders, artists and entrepreneurs who found the store’s counterculture ethos appealing.

With success came brand collaborations big and small — all tightly controlled by Jebbia, who is renowned for unfailing business instincts — ensuring waiting lists and lines at new product launches. A 2012 partnership with Comme des Garçons brought Supreme avant-garde fashion followers with deeper pockets.

“I don’t think enough people take risks, and when you do, people respond — in music, in art, in fashion,” Jebbia told Vogue. He seemed to be taking a risk working with big brands. But although some fans accused him of selling out with Supreme’s Fall/Winter 2017 collaboration with Louis Vuitton, most did not, including the winning bidder for the Malle trunk at Christies. Jebbia must have enjoyed the irony of his collaboration with Vuitton earning top auction honors some two decades after the luxury brand served Supreme with a cease and desist order for using its trademark logo on a skateboard deck without permission. He may also have appreciated the earlier irony of Vuitton’s hiring Marc Jacobs as creative director just a year after it sued Supreme, in 2001. Jacobs, another bad boy, immediately collaborated with downtown artist Stephen Sprouse to create what today is considered by all in the fashion business the seminal artist-corporate collaboration: the fabulously successful LV bag with the brand’s iconic logo converted to orange graffiti scrawl. It reinvigorated the company and made it front of mind with a new young buying demographic. A year is a long time in the fickle world of fashion!

Left: Tyshawn Jones at République, Paris, 2017 (photo by Alex Pires). Right: Cindy Sherman skateboard decks, 2017, from Supreme (Phaidon)

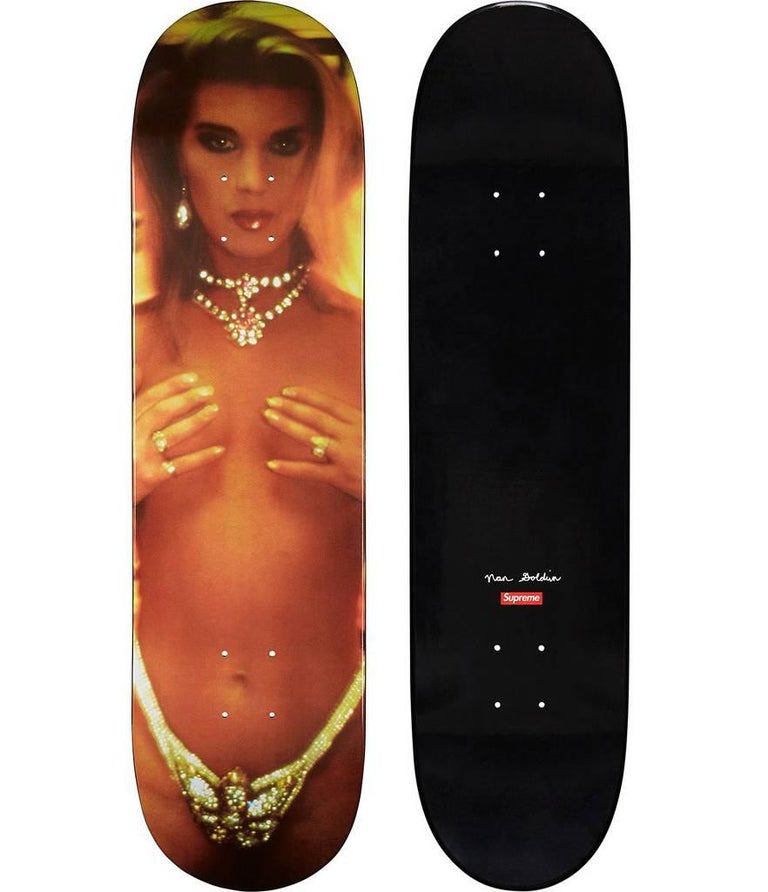

A curated “Artist Series” of Supreme skate decks was inaugurated in 2001 when the then-not-so-famous street artist KAWS, aka Brian Donnelly, designed his Chum boards, a pair of which, signed, went for $32,000, four times their estimate, at the “Handbags X Hype” sale. Supreme Volume 2 has many examples of the series, which now includes creations by Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, Damien Hirst, the Chapman Brothers and George Condo.

i-D Magazine ad, 2016. Photo by William Strobeck

A vast range of designs from the later years covered in the book demonstrates Jebbia’s penchant for working with unexpected brands, always switching it up, making uncool cool. There were tight runs of each edition, and they were never repeated. Aquascutum, a stolid English middle-class staple, in Supreme’s hands became a must-have from Paris to Tokyo. Apparent Jebbia favorites like Undercover, Everlast, The North Face, Nike, FILA and Hanes are shown alongside Thom Brown and Brooks Brothers (yes, Brooks Brothers). The volume also displays Supreme’s own anonymous product designs, like the 2018 packet of poppy seeds, an edgy allusion to opium as well as to the beautiful flower used to memorialize those who died in World War I.

Celebrities like Kate Moss, Michael Jordan, Tyshawn Jones and Javier Nunez appear in ads alongside images captured in the streets and in the stores. Stills from videos created for Supreme by William Strobeck and others are included as well. Among these is Ben Solomon’s brilliant 2011 aerial video of the Supreme logo banner being flown over the Statue of Liberty, the symbol of freedom at the gateway to the country of commerce.

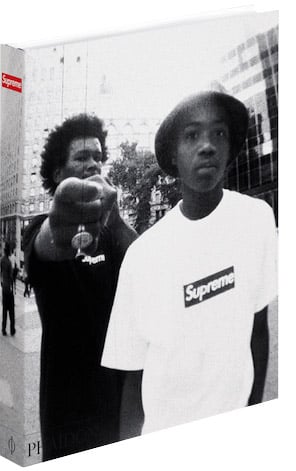

Supreme Vol. 2 (Phaidon)

Jebbia’s marketing genius is evidenced by the stark name and logo. The latter — realized in italicized white lower case Futura Oblique within a red band — is a stimulating alert. It subverts artist Barbara Kruger‘s most popular piece from 1987, “I shop therefore I am,” itself, of course, a twist on Descartes’s best-known quote, “I think therefore I am.” Whether Jebbia thought about it or not, the Supreme logo stands conspicuously for anti-materialism while paradoxically — subliminally? — exhorting the consumer to buy. His business is therefore him.

Supreme’s ascent from 1994 neighborhood cult favorite to 2019 auction star is a master class in brand marketing, based on creating hard-to-build desire. Behind the hype is an authentic truth: Great stuff sells — it did then, does now and always will. After 25 years, Supreme might not yet be a heritage brand, but it has made history in the fashion crossover scene. Is it art, or is it marketing genius? Who cares! Supreme does not so much collaborate as it colludes, creating tantalizing products that cannot be denied. The images in Supreme Vol 2 reveal a thought-provoking and enjoyably paradoxical kind of unexpected business as usual. If you get it, get it. If you don’t — well, you know.