May 15, 2017William Hall’s new book highlights innovative wood structures around the world, like this hotel lobby in Australia. March Studio hung pieces of lumber discarded during construction from steel rods throughout the lobby (photo by Peter Bennetts). Top: Located in a nature reserve in Germany, the Bird Observation Tower, designed by Architekten von Gerkan, Marg und Partners, has an abstract avian shape and a viewing room 49 feet off the ground (photo by Heiner Leska).

Iwan Baan, the renowned architectural photographer, hit pay dirt when he traveled to Kumamoto, on the Japanese island of Kyushu. Baan was accompanied by Sou Fujimoto, a young Japanese architect who had just completed a tiny house there made of wooden beams as thick as railroad ties. Baan knew the house was photogenic, but even he didn’t realize his shots would end up in hundreds of magazines, on thousands of websites and in coffee-table books, including William Hall’s new picture-filled tome Wood (Phaidon)

Why this popularity? What Fujimoto had created was an ode to wood in all its permutations. The exterior was wood. The interior (floor, ceiling, and walls) was wood. And the furniture was hewed from the same large timbers as the house itself. Nothing but wood, in a composition that was both as comforting as a cocoon and as intriguing as a puzzle box. The house would be impossible to live in. It would also be impossible not to fantasize about living in it.

No building material has a greater hold on the imagination than wood. Architects gravitate to it, although countless other materials have come along that make it unnecessary in the building process. And the appeal of wood appears to be universal, given the geographic range of the 200 or so projects Hall covers in his book, from Canberra to Oslo. (A disproportionate number are in Japan, where intriguing uses of wood seem to crop up daily.)

Wood’s core function is structural. As Richard Mabey, a British nature commentator, writes in the book’s introduction: “All trees, whatever their form, face the fundamental problem of raising a mass of wood, foliage and fruit into the light, and against the forces of gravity.” In other words, wood comes into the world as structure.

And, in many cases, structure it remains. Too often, that structure takes the form of two-by-fours hidden behind lesser materials. But merely arranging two-by-fours in an artful composition can make a building seem to soar, as evidenced by the Whittier, California, SkyRose Chapel by the late E. Fay Jones.

This structure was created by Arne Quinze for the 2006 Burning Man Festival in Nevada. It took 25 people more than three weeks to build it, and they did so without a model. At the end of the festival, it was set ablaze. Photo by Jason Strauss

Shigeru Ban, the Japanese Pritzker Prize winner, is represented by a clubhouse in South Korea where wooden beams rise toward the roof like branching trees, a use of the material that is richly metaphoric. (Ban is a structural innovator at every scale; his chairs of plywood and cardboard tubes are classics.)

Sometimes, wood forms orderly compositions, as in the grid that covers Ban’s art museum in Aspen, Colorado (a town, fittingly, named for a tree). Other times, it is allowed to follow nature’s unruly course. The sculptor Andy Goldsworthy wove 760 sweet-chestnut branches into a dome at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in England. The result suggests an upside-down bird’s nest.

The book is filled with examples of wood employed in unexpected ways. Designer Piet Hein Eek created a garden studio in Hilversum, the Netherlands, out of thick birch logs displayed in cross section. The building recalls Eek’s furniture designs, which include cabinets that impersonate stacks of unfinished lumber.

Wood can be bent into surprising shapes, employing methods long known to furniture designers like Eero Saarinen and Alvar Aalto but increasingly employed at building scale. Studio Gang Architects used bentwood panels to shelter outdoor classrooms at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago.

“All trees face the fundamental problem of raising a mass of wood, foliage and fruit into the light, and against the forces of gravity.”

But wood is as much a surface material as structural one. Its grain represents decades (sometimes centuries) of growth, which makes it a storyteller par excellence. No other material displays its history so clearly.

As a surface material, wood can be light or dark, smooth or rough. It can be left as is or altered with myriad chemical and physical processes. It can even be burned. A forest retreat in the Czech Republic by Uhlik Architekti is covered in boards that were deliberately charred, “giving the structure a monolithic, object-like quality,” according to Hall. (The Dutch designer Maarten Baas chars wooden furniture for roughly the same reason.)

Winning Wood Furniture on 1stdibs

The design of St. Henry’s Ecumenical Art Chapel, in Finland, by Sanaksenaho Architects, was inspired by the Christian fist symbol. The structure is made of copper-clad, locally sourced pine. Photo by Jussi Tiainen

Groups of boards that are glued or bolted together tightly can be treated as a single unit. A viewing platform in Norway’s Dovrefjell-Sunndalsfjella National Park has a facade of 10-inch-square pine beams milled into a single, swoopy surface. Designed by Snøhetta, the building bears a strong resemblance to the work of Massachusetts-based artist Michael Coffey, who gives the surfaces of chests and credenzas spectacular, seemingly wind-swept, recesses.

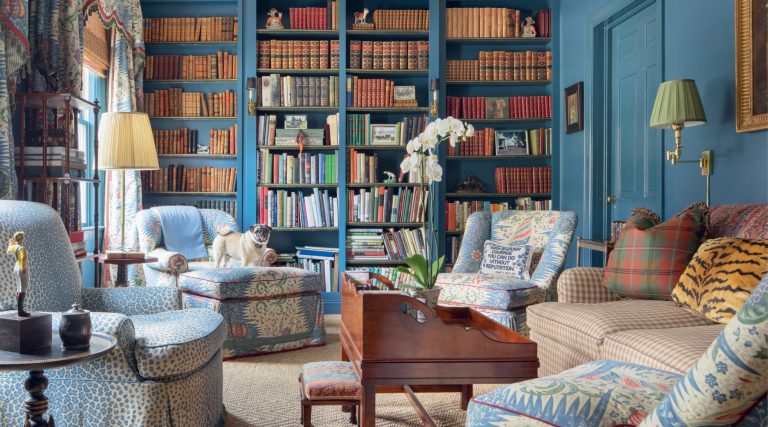

In Canberra, Australia, March Studio collected 5,000 pieces of lumber discarded during the construction of a hotel and hung them from steel rods to define zones in the hotel’s sprawling lobby. There, the wood is rough yet sophisticated.

It can be a foil to slick surfaces. Phillip K Smith III alternated strips of wood and mirror on the facade of a house near Joshua Tree, California. That juxtaposition, according to the book, transforms “an unremarkable shack into an inscrutable and mysterious object in the landscape.”

Wood can warm up the coldest building, as MAD Architects showed when it installed Manchurian ash balconies and stairways in its bright-white opera house in chilly Harbin, China. Wood, with its texture and grain, keeps the building from looking like a model of a building.

Wood, following the lead of its one-syllable title, is light on text. Instead, its pages are filled with one startling image after another. Which makes this handsome volume hard to put down. There is nothing as compelling as a wooden building, except perhaps the photo of a wooden building.

Or Support Your Local Bookstore