December 13, 2020Since the dawn of recorded history, paintings of people have persisted, no matter which trends took over the “art world.” All through the artistic upheavals of the past 100 years — from Futurism to Abstract Expressionism, Op art to word art — a certain kind of figurative approach held its own. Artists like Alfred Leslie, Philip Pearlstein and Alex Katz, all of whom are now in their 90s, continued to mine a vein of realism that still sparks interest among collectors and curators.

Katz, in particular, has remained a strong presence, attracting an admiring audience of curators and collectors with his hard-edged oversize portraits of the hip and the beautiful and with simplified but radiant landscapes of rural Maine. (A 10,000-square-foot wing is dedicated to his works at the Colby College Museum of Art and a new monograph was published last month by Rizzoli.)

Meanwhile, the arresting proto-Pop portraits of David Hockney, the 83-year-old British artist who inarguably counts as an Old Master among figurative painters, continue to command attention. His coolly composed 1971 likeness of the Royal Opera’s general administrator, Sir David Webster, sold for $16.9 million in October at Christie’s, and an overview of 125 of his drawings from his student days to the present is at the Morgan Library in New York through May 30, 2021.

Portraiture, in particular, never really loses its appeal, especially among the elite. The nobles and leaders of antiquity saw themselves immortalized in marble, and the practice of calling on artists to capture notoriety or celebrity persisted through the Renaissance right up to today. A portrait, whether it’s by Hockney, Annie Leibovitz or Kehinde Wiley, confers status and places the sitter in a long tradition of art historical approbation.

Given the sizable number of younger artists who have followed the figurative muse, one could speculate that art that takes as its subject the human body speaks more to our times than any other idiom. And in true postmodern fashion, artists now feel free to plunder art history for props and poses that they use to riff on traditional formulas.

Angela Fraleigh, for instance, employs favored Rococo subjects to shed new light on the nexus between gender and mythology. Daisy Patton looks to old studio portraits to create a fresh dialogue between photography and painting. Mark Steven Greenfield puts a new spin on religious iconography of the Renaissance and Middle Ages.

Those talents are among six figural artists we’re shining a spotlight on here.

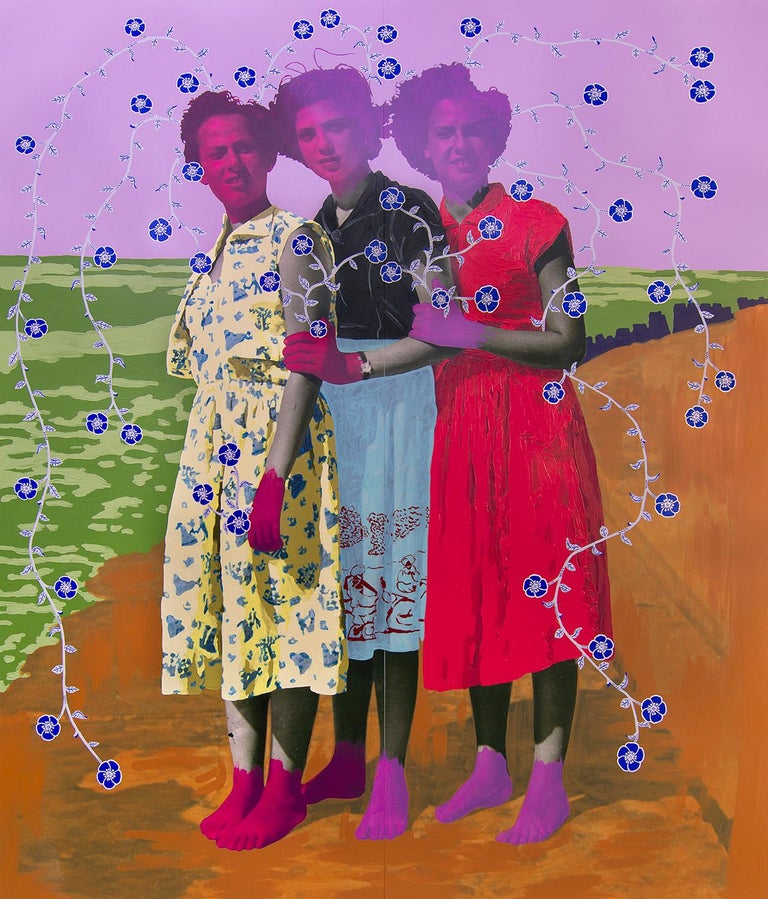

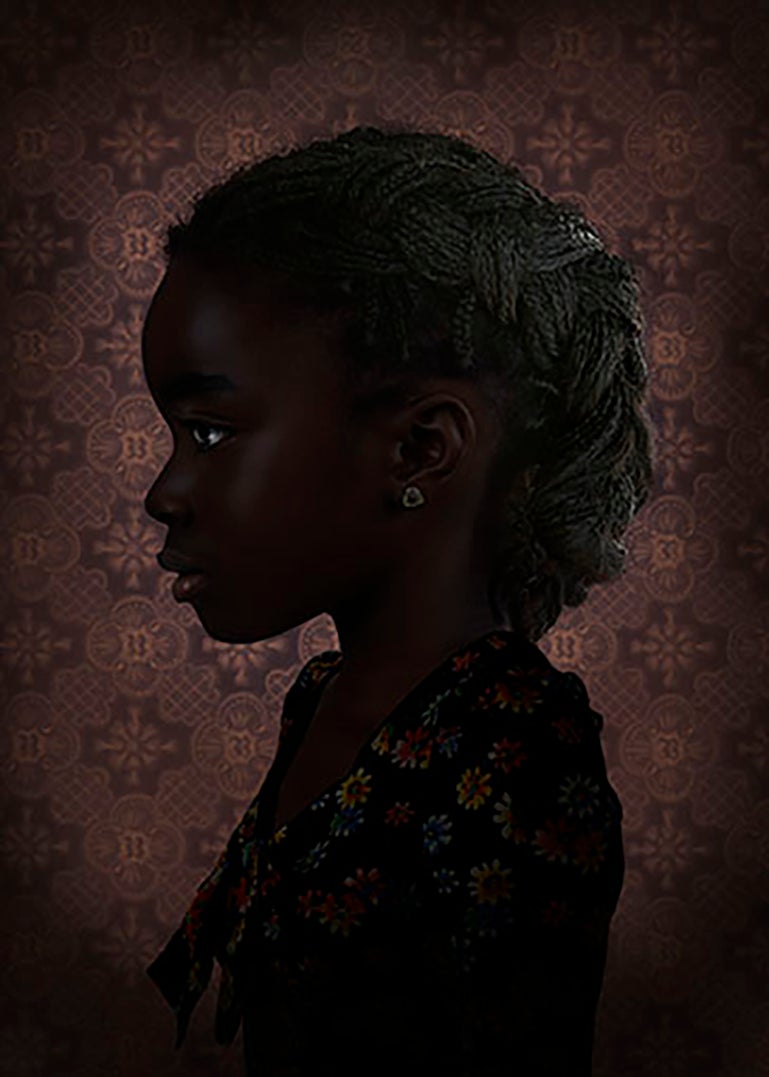

Daisy Patton

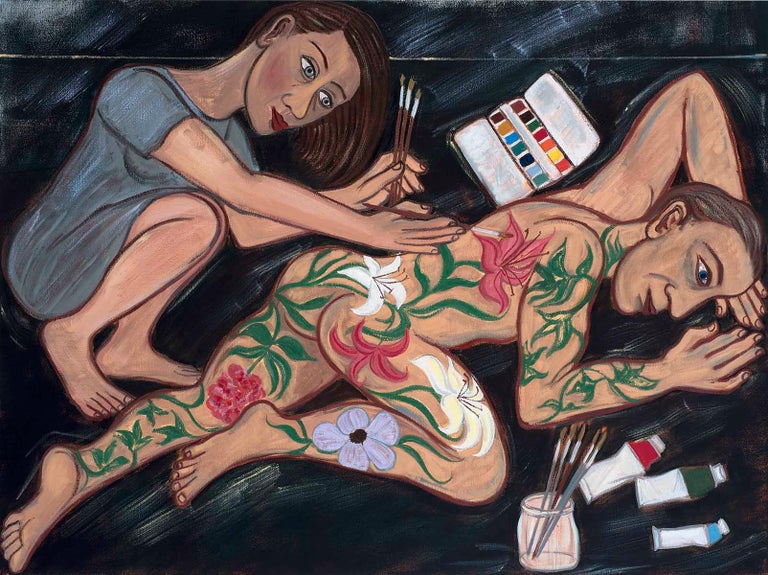

Daisy Patton’s cheerfully dysfunctional portraits are bound to remind you of pictures from somebody’s attic, those old crinkle-edged Kodak photos or studio shots that commemorate engagements, high-school graduations and informal family get-togethers. Yet there are sharp and unsettling differences.

Faces may be obliterated with garish masks of color, outrageous patterns take over sedate everyday attire and creeping vegetation threatens to engulf the unsuspecting subjects.

Patton has been fascinated by photography’s slippery documentary function, and by the artist’s role as voyeur, since before she received her MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University in Boston in 2011. In many of her series, Patton enlarges old studio photographs and embellishes them with inks or paint, often conferring a giddy surreality to the original subjects.

Other works are realized in embroidery or more traditional mediums like watercolor or oil on panel. In less than a decade, she has produced several striking bodies of work, a few of which are ongoing.

“Patton veils, conceals and reveals elements of the human figure in a way that entices the viewer to rediscover the familiar intricacies of human nature,” says Dariya Bryant, director of K Contemporary, in Denver. “Her delicate floral patterns lead the eye through the composition with intent, enveloping the viewer in a reverie of memory, identity and loss. Drawing attention to the facial expressions, hands and limbs — parts that express our innermost feelings outward — Patton relays the individual stories her subjects once lived and gives tribute to these lives in a beautiful, sorrowful, yet hopeful way.”

During the past few years, partly in response to the conservative political tide, Patton has been developing two series about reproductive rights — specifically, the issues of illegal abortion and forced sterilization (between 1907 and 1963, some 64,000 people were forcibly sterilized under eugenic legislation in the United States).

“These issues are two sides of the same coin,” she says. “The general public doesn’t remember how awful it was before Roe v. Wade, how many women died from abortions. I’m doing a lot of research, trying to find pictures of women and seeking out women who may still be alive who suffered forced sterilization.”

Patton’s art is teasingly ingratiating; often, its radical underpinnings take a while to digest. But when they do, the message packs a wallop.

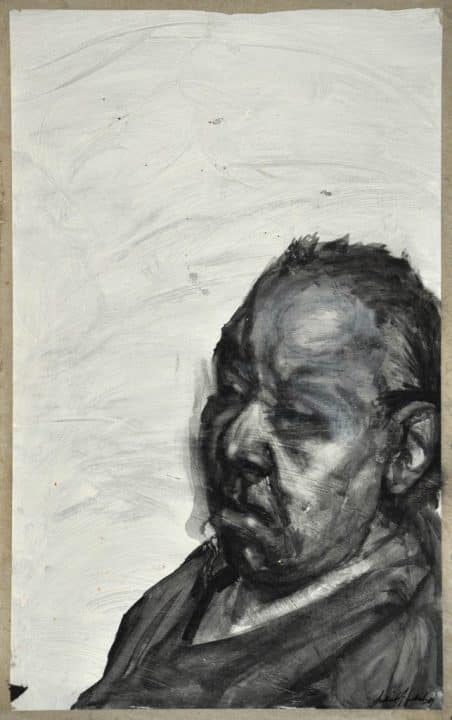

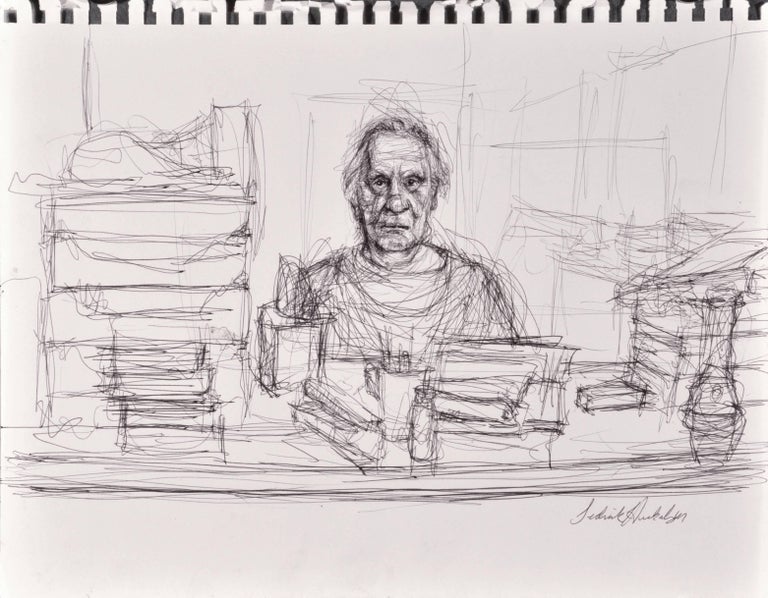

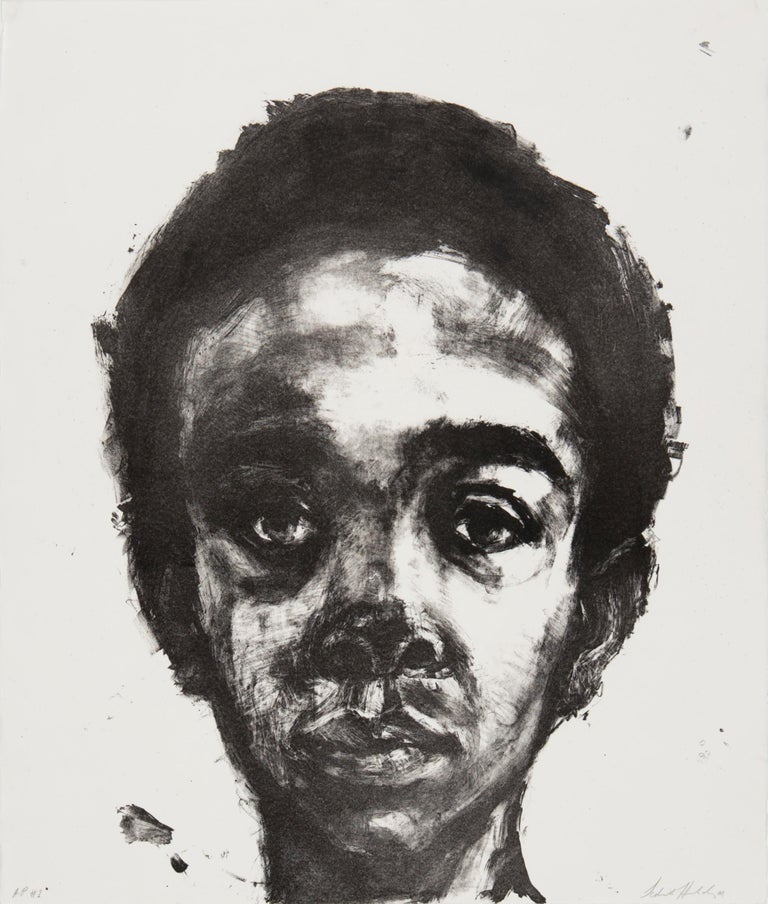

Sedrick Huckaby

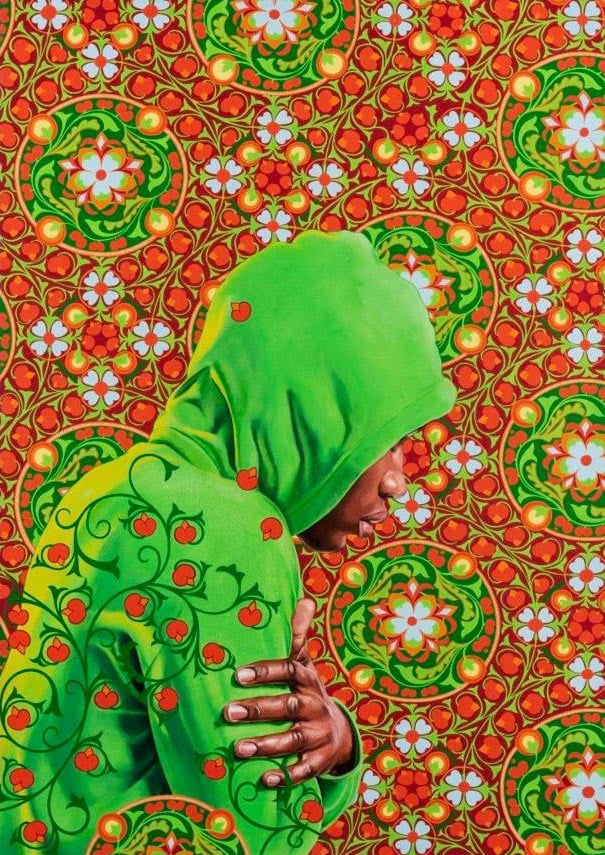

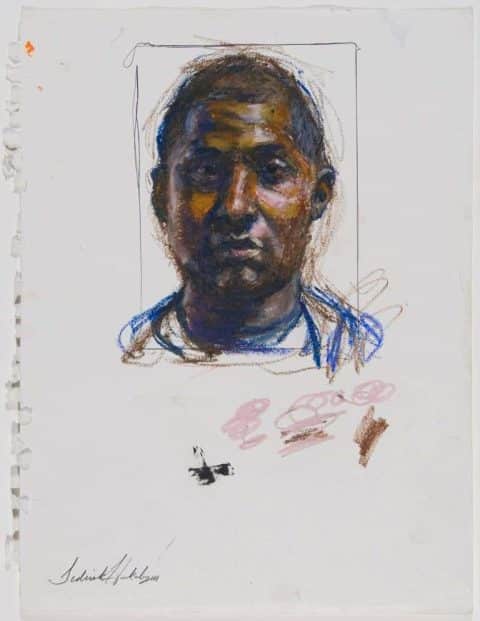

Sedrick Huckaby may be best known in Texas as George W. Bush’s art teacher and the author, with his wife, Letitia, of a huge piece of protest art in Fort Worth, completed in June (the words “END RACISM NOW” fill part of a city block on Main Street). But for two decades, the 45-year-old artist has had a solid career as a portraitist and figurative painter in the traditional mediums of oil on canvas and graphite on paper.

It’s no accident that many of his works have an Old Masterly presence — the artist spent two years traveling through Europe after obtaining his MFA from Yale. But Huckaby’s subjects are drawn from his roots.

“The African-American family and its heritage has been the content of my work for several years,” he says on his website. “In large-scale portraits of family and friends I try to aggrandize ordinary people by painting them on a monumental scale.” Among his projects are “Big Momma’s House” (2008), 65 paintings, pastels and drawings celebrating his maternal grandmother, Hallie Beatrice Carpenter, the matriarch of the family.

Three years later, “The 99%” installation featured 101 portraits of Huckaby’s neighbors from Highland Hills, a predominantly Black community in south Fort Worth (the works are now in the permanent collection of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art). Huckaby’s other grandmother, Mama Sarah, inspired the series “A Love Supreme” (2001–9), comprising monumental paintings that stretch to 20 feet across and push the quilt, a familiar domestic icon, into the realm of pure abstraction.

Patterns and folds march across the canvas in homage to the dazzling ingenuity of African American quilt makers. Past and family infuse all of Huckaby’s works, but he claims he is “most enthusiastic about painting from a live sitter. There is an incredible energy when painting directly from another person, and I love the challenge.”

“Sedrick Huckaby paints monumentally scaled heads — eighty inches tall is not uncommon — of his family and relatives to emphasize the importance of this social and spiritual unit and the role each individual family member plays in it,” says Cheryl Vogel, co-owner of Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden, in Dallas. “His most recent works of full figures focus on the communal loss of Black mortality. Using direct observation, Huckaby paints frontal portraits with bold brushwork and an impasto surface that can border on relief sculpture.”

Ruud van Empel

There are a number of disquieting aspects to the photocollages of Ruud van Empel, a Dutch artist who has gained an international following that includes Elton John, who dedicated a song to him.

His wide-eyed children, both of African and of European descent, project an innocence reminiscent of storybook illustrations or even the kitschy big-eyed kids painted by Margaret Keene. They are often exquisitely dressed, in clothes that look stylish but slightly out of date. They frequently inhabit improbable settings — a lush forest setting, a moonlit desert or jungle — again reminiscent of fairy tales. But the unreality of these beguiling kids owes much to the process by which they were created.

They have been photoshopped into being through a patchwork of features manipulated on the computer. The settings they inhabit also come about through photocollage: The Guardian reported that van Empel wanders “through Dutch forests, in search of fine leaves, perfect branches, and the right waters. Only to tear it apart and spend weeks reconstructing it all until both the person and the setting match his desired standard of photo-realism.”

Van Empel was born in the small town of Breda and studied at the local art academy before moving to Amsterdam to pursue a serious career as a fine-art photographer. The earliest series to attract critical interest, “The Office” (1995), depicted staid office workers amid improbable props, referencing early 20th-century photomontage. As he has matured as an artist over the past 25 years, however, he has mastered a kind of realism that is somewhere between magical and dangerous.

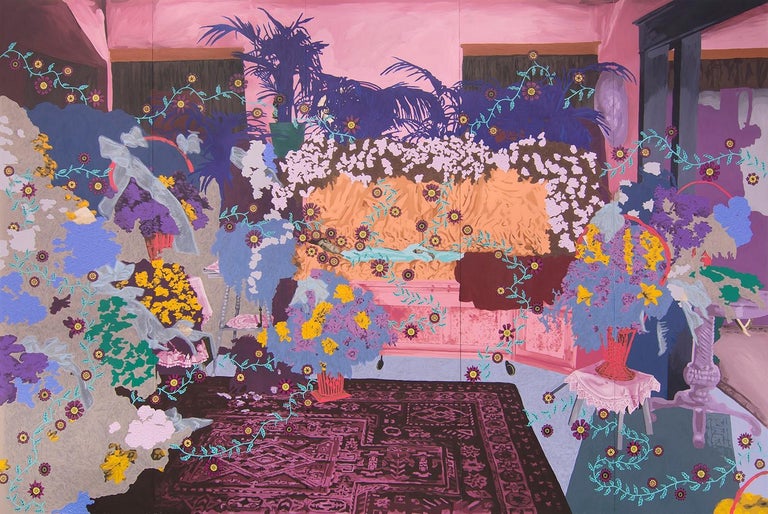

Angela Fraleigh

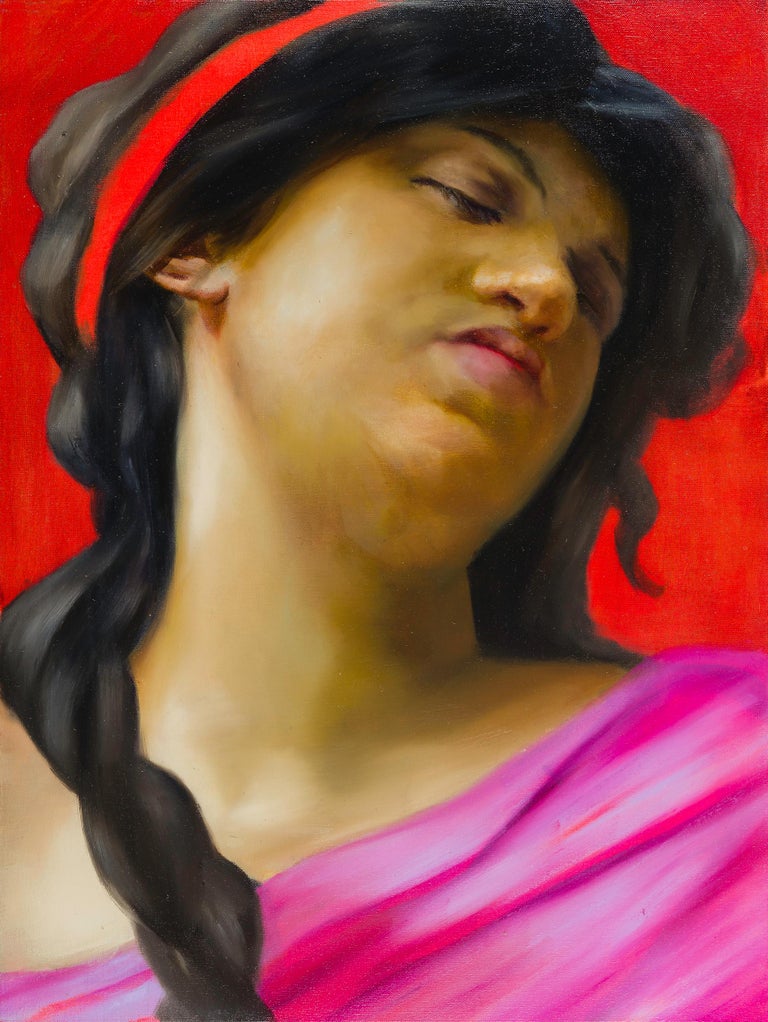

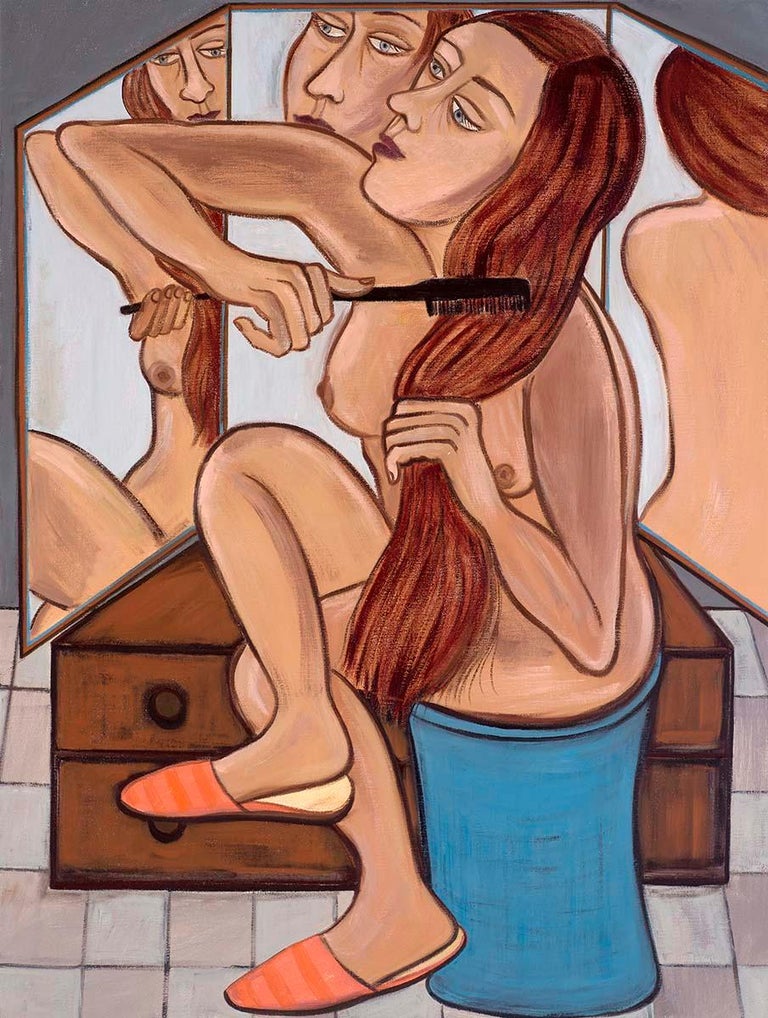

Many of Angela Fraleigh’s haunting and carefully staged tableaux feature women drawn from the annals of Baroque and Rococo “boudoir paintings” — titillating scenes meant to fan the ardor of the viewer. But she puts a contemporary twist on this iconography by giving her characters more agency than was typical of earlier eras.

In these pictures, which can extend to eight feet, group scenes are typically set against a backdrop of lush painterly effects, ranging from pure abstraction to suggestions of flora and fauna. “I want my paintings to be magical and mesmerizing — seductive, while also inspiring the viewer to ask questions about who they are, where they are, what power they have available and how they might use that power,” the artist says.

Adds Ted Holland, a director at Hirschl & Adler Galleries, in New York, which represents Fraleigh’s work: “She examines the roles and depictions of women in art history — as subject, object, artist and muse — and repositions those often-marginalized figures at the center of her own paintings. The mix of figuration and abstraction allows the female figures to exist without the signifiers of time and location, ultimately giving the figures a new power and context.”

But Fraleigh’s practice also has a quieter, more intimate side. She is an exquisite draftsman who has focused on, among other subjects, the animal kingdom and the intricacies of women’s hair, and some of her smaller paintings have a quiet mystery reminiscent of Gerhard Richter’s tender portraits.

Eileen Cooper

British figurative art has a reputation for trending toward the dour, the dark or the tortured. Think Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach and Francis Bacon. But Eileen Cooper’s paintings and woodcuts are dreamy and humorous, with a man giving a woman a foot rub or a woman tenderly cradling a rabbit. In her world, a couple drifts happily on a sea of love; sisters embrace; and cats, bears, and foxes show up as benign companions.

Cooper has said that she has a head full of stories: “Mythology, fairy tales, Bible stories, fables and early special-effects movies — they’re all part of my work even if it’s not obvious. I always try to look spontaneous.”

Alongside her artistic practice, Cooper has maintained a teaching career at institutions including Central St. Martins, the Royal College of Art and the Royal Academy Schools.

She became an Academician and Keeper of the Royal Academy Schools in 2010 (the first woman Keeper since the RA’s founding, in 1768), and in 2016, she was made an Officer of the British Empire (OBE) for her services to art and art education.

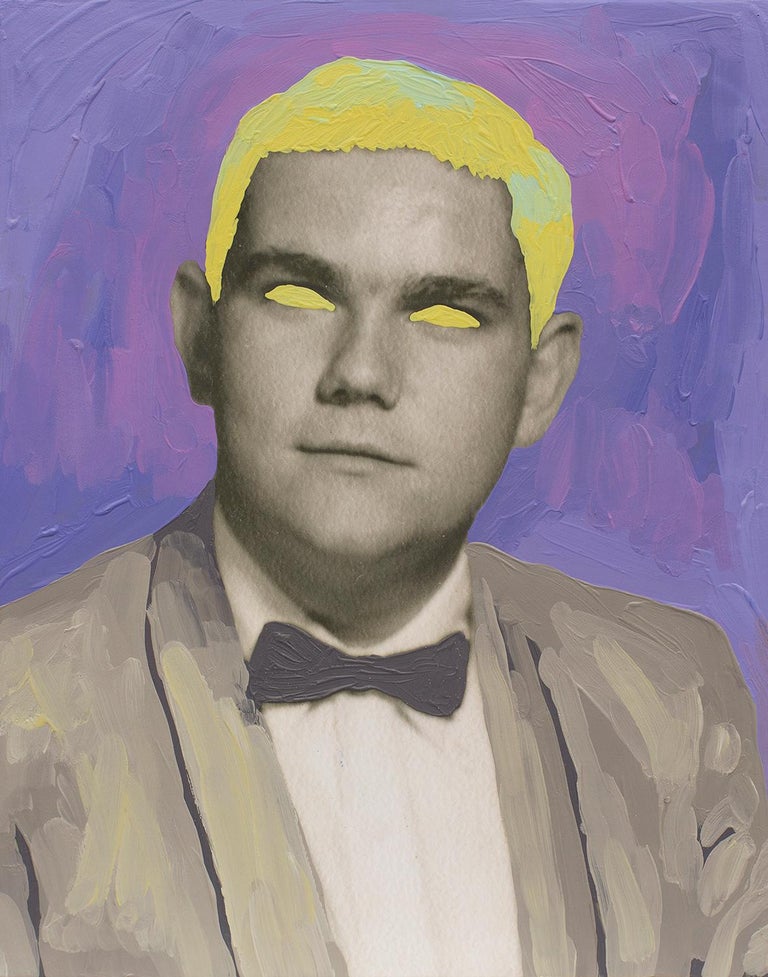

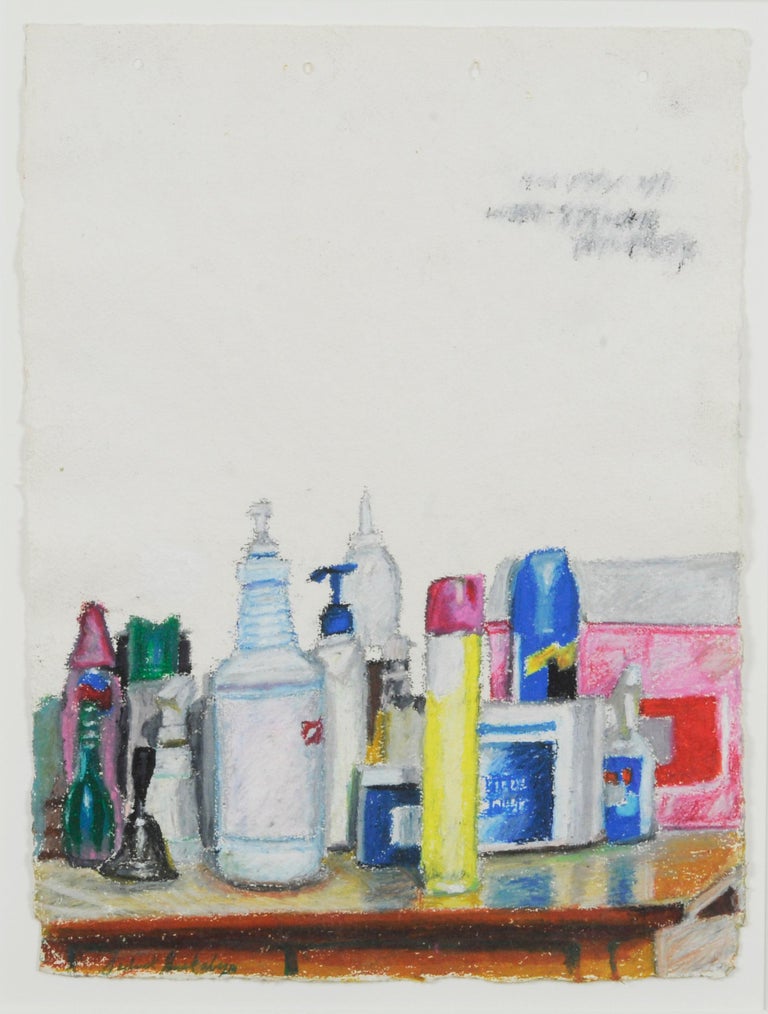

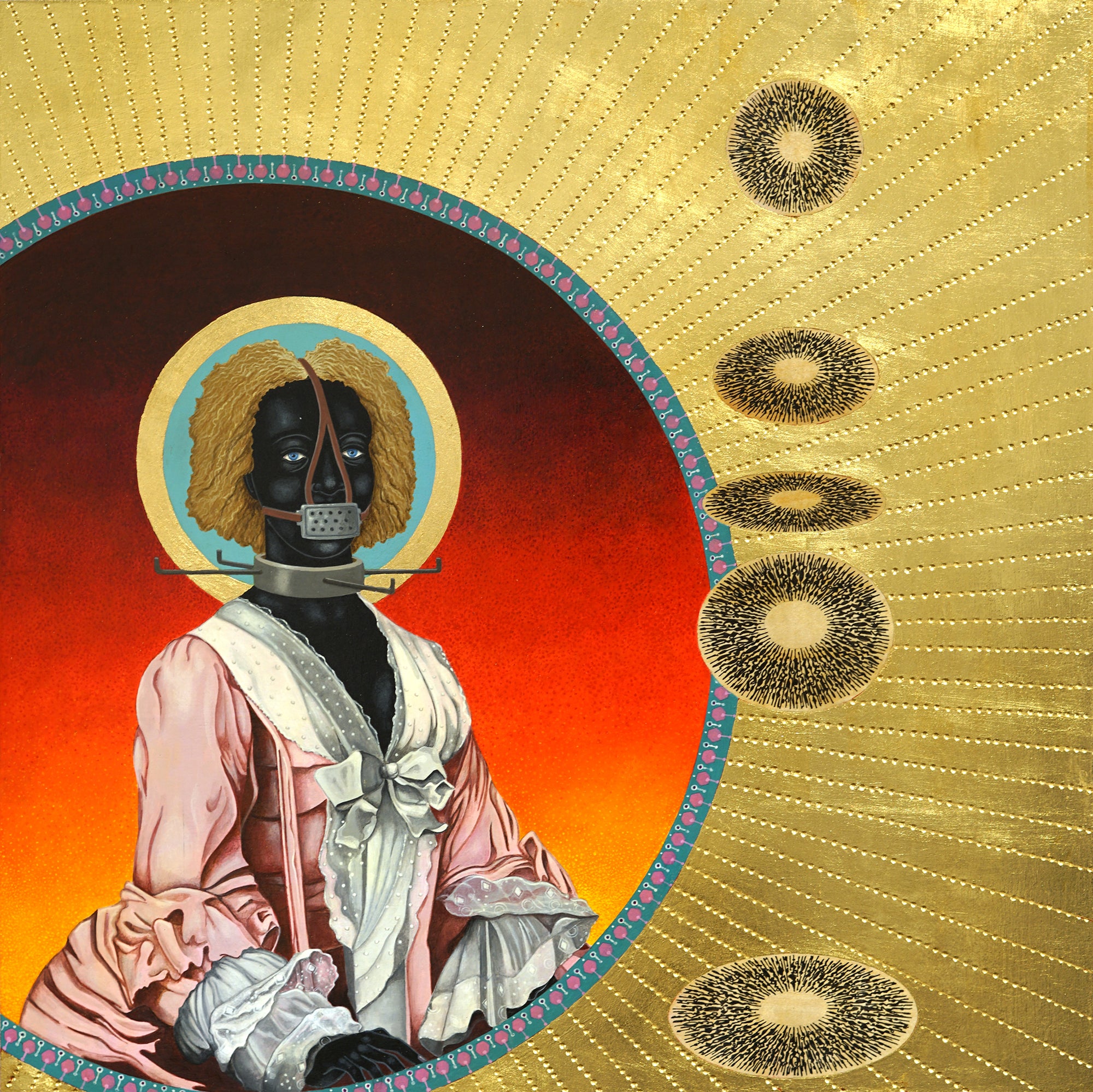

Mark Steven Greenfield

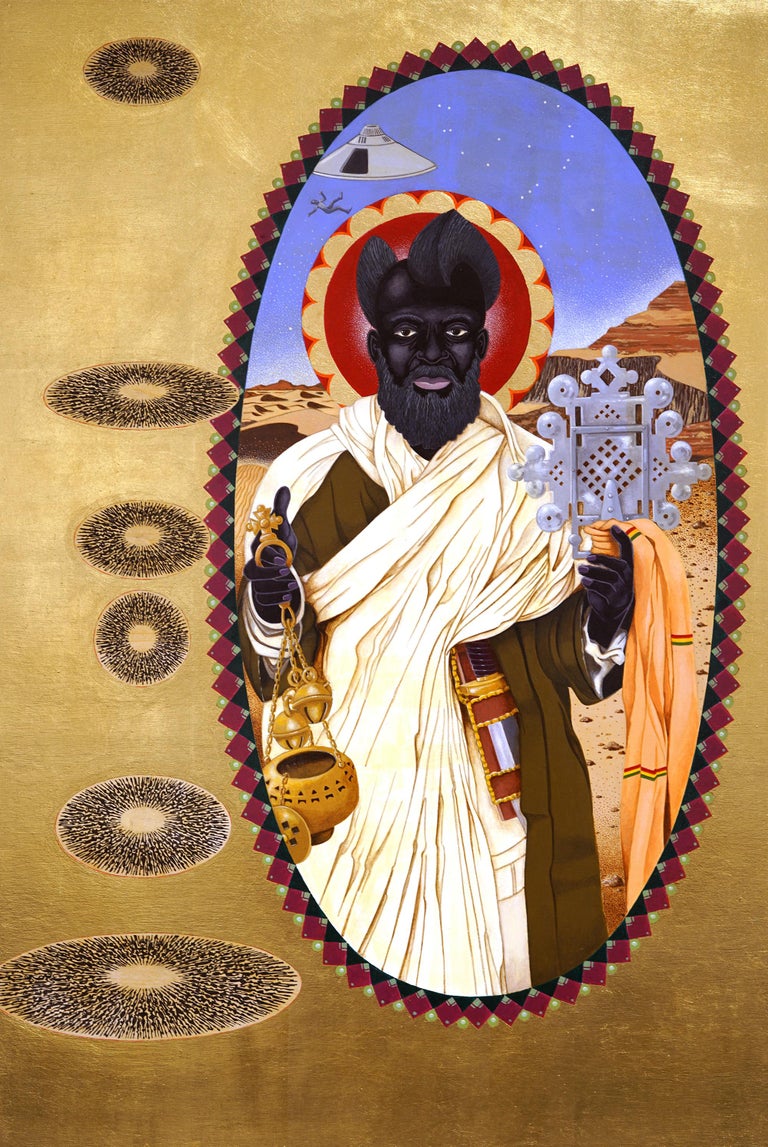

After earning a graduate degree from Cal State in 1987, Los Angeles–based Mark Steven Greenfield launched his career on the West Coast riffing on some of the more offensive stereotypes of Black Americans in popular culture — for instance, the theatrical tradition of blackface and the ways in which “ethnic” characters were portrayed in cartoons, many of them so insulting they have since been banned.

“There’s been an entire generation that didn’t even now these things existed,” he has said. Of the “Blackatcha” exhibition, which superimposed blurbs in the form of eye charts on photos of blackface characters, he has remarked, “If you are discomforted by what you see, I invite you to examine those feelings, for out of this examination will come enlightenment.”

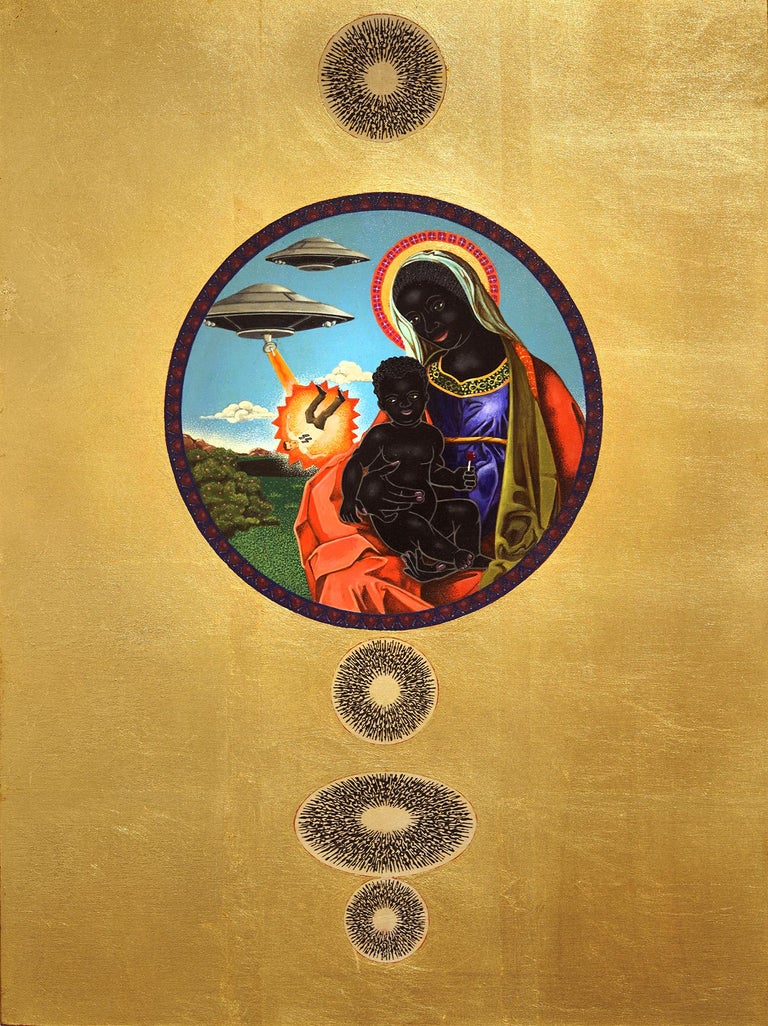

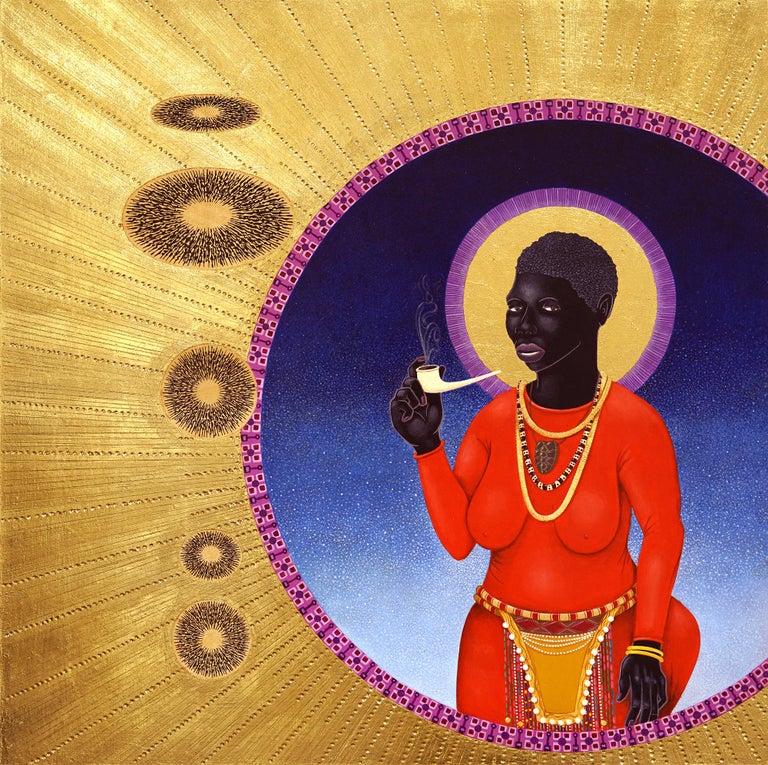

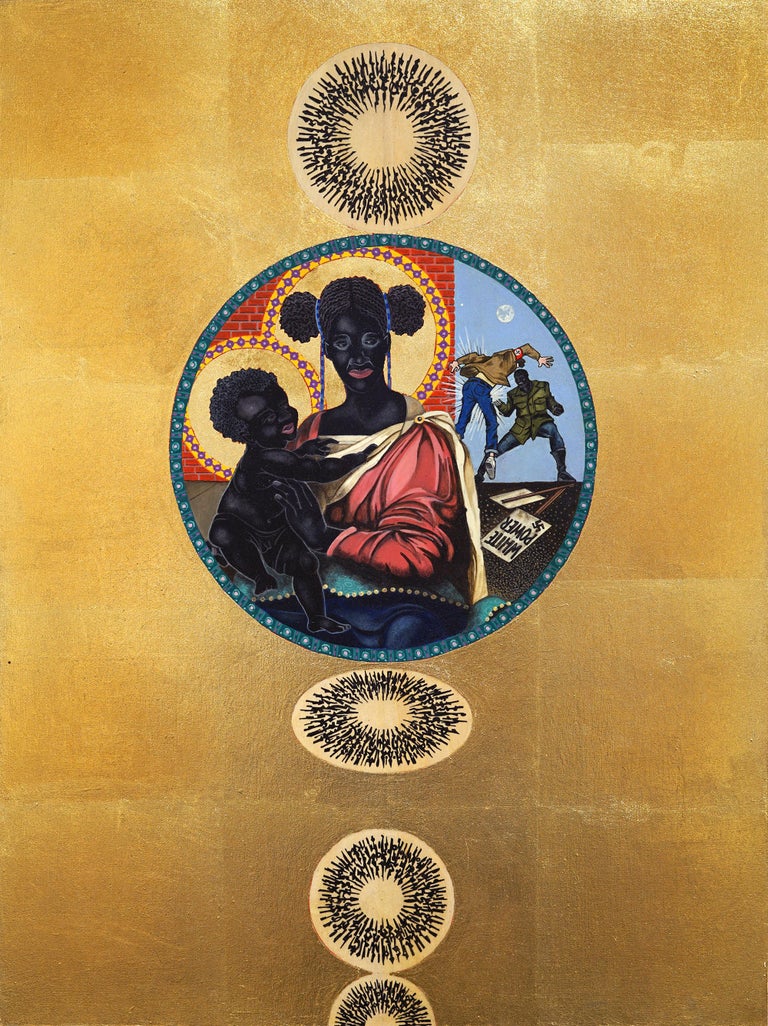

A different kind of discomfort prevailed in his recent series of Madonnas, exhibited at William Turner Gallery in 2019. The coal-black mother-and-child figures, borrowed from Renaissance masters yet still hinting at the blackface tradition, are positioned within tondos and surrounded by fields of burnished gold leaf. In the backgrounds are scenes of outrage — marching Nazis, a gas chamber — or little vignettes of white supremacists getting their comeuppance.

Greenfield can playfully subvert time-honored genres by toying with art history and tossing in modern artifacts. In one triptych, a Black Pietà, a trope borrowed from Michelangelo’s famous statue of the adult Christ in his mother’s arms after the Crucifixion, hovers in front of elaborate Gothic arches, while snazzy running shoes lie piled on the ground.

The works’ subjects are unsettling, but Greenfield shows a huge respect for craft in their realization. These paintings are a cunning mix of postmodernist irony, pointed social commentary and pure optical delight.